A Short History of America’s ‘Tamale Wars’

Their popularity made for some bloody turf wars.

Food trends don’t usually incite extreme violence. But in early 20th-century America, the popularity of one recently arrived street food caused turf wars, which the media breathlessly sensationalized. That food, as it happened, was the humble tamale.

At the time, the tamale quickly became as popular in America as the hot dog. As Gustavo Arellano writes in Taco USA: How Mexican Food Conquered America*, tamales made a splash at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, and more and more Americans were moving West into what had previously been Mexican territory. There, they encountered cheap, filling tamales, and they liked them. Hilariously, the Atlantic Monthly explained tamales to unfamiliar readers in 1898: “The hot tamale (pronounced ta-molly)—a molten, pepper-sauced chicken croquette, with a coat of Indian meal and an overcoat of corn husk.” For many white Americans, with their uninitiated taste buds, eating something so spicy was a revelation: The Atlantic Monthly went on to describe the taste of a tamale as “a diabolical combination that tastes like a bonfire.”

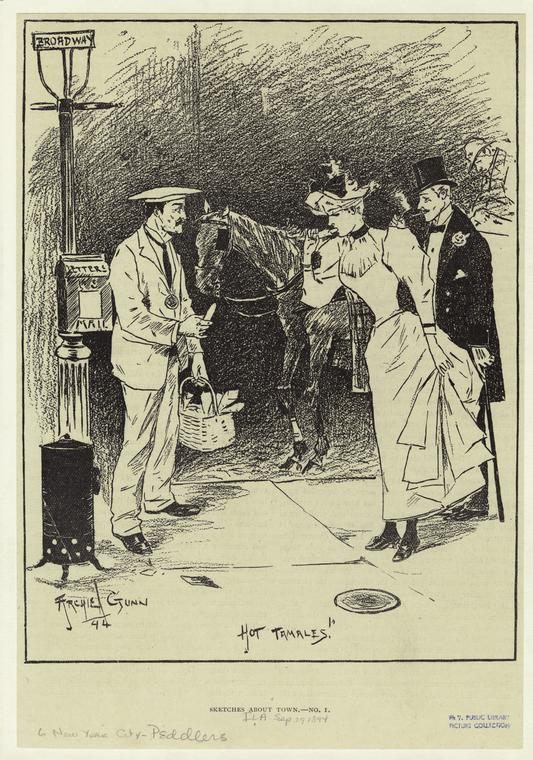

Tamale vendors canvassed the growing cities of the West, serving their wares out of kettles, carts, and wagons. Cries of “Hot tamales!” or “Red-hot tamales!” soon became part of the soundscape. Men and women of all ethnicities became tamale vendors, and business was good as city-dwellers sought late-night and cheap eats. But perhaps business was too good. In 1893, a fictional short story, entitled Love and Tamales, detailed a Romeo-and-Juliet story of white and Mexican tamale vendors butting heads over business (with all problems eventually solved by a marriage between the two sides).

But the reality wasn’t so harmonious. Soon, newspapers published lurid tales of “tamale wars”: beatings and murders between rival tamale sellers. In 1921, the Omaha Daily Bee reported on a party held by “competitive ‘hot tamale rings’” where one member of tamale-selling business hacked another to death with an axe. (The party had been an attempt at reconciliation between the two sides.) Other battles between tamale vendors consisted of near-riots over turf in Arizona, counterfeit tamales in Washington, and a saloon shoot-out between two rival vendors in Kansas.

While violence did happen, the ethnicities and social status of many tamale sellers also meant increased scrutiny. In a profile of legendary tamale seller Zarif Khan, New Yorker writer Kathryn Schulz points out that tamale vendors in America were poor or minorities: Mexican, of course, but also Italian, Middle Eastern, and African-American. Tamale vendors were spun as hot-blooded stereotypes in the press and fiction, fighting over turf and business. Stories about their battles often became front-page news.

In the end, the waning of the tamale’s popularity put an end to both tamale fights and most tamale vendors. According to Schulz, demand slackened throughout the 1910s as the tamale trend ran its course. Many former vendors turned to other careers: ones which, hopefully, involved less warfare.

*Update 9/4/18: This post has been updated to cite the work of Gustavo Arellano, who researched and wrote about the history of tamale vendors in his book “Taco USA.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook