Debunking the Myth of 19th-Century ‘Tear Catchers’

It’s hard to keep a good story down when there’s money to be made.

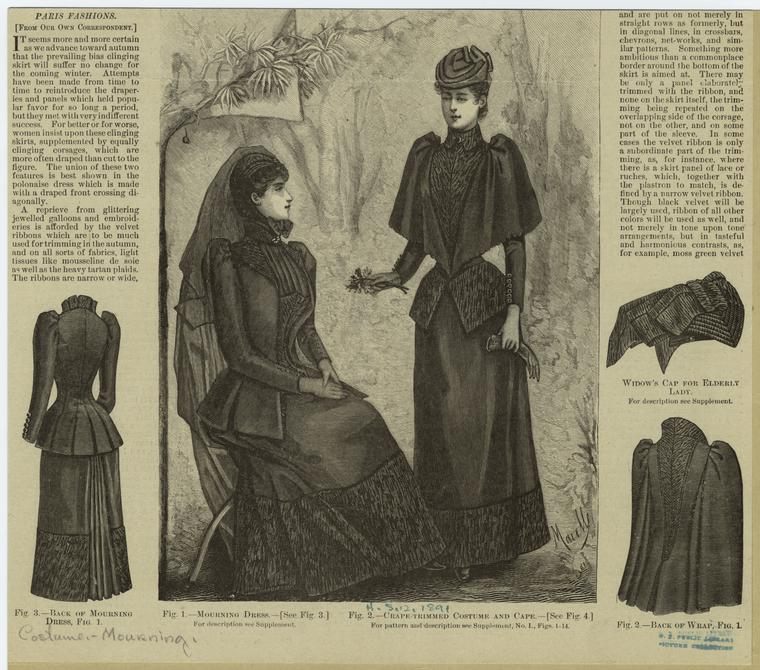

The Victorians were experts in the art of mourning: They wore black for extended periods, wove human hair into elaborate wreaths, and wept, it is said, into delicate glass bottles called “tear catchers.” Victorian ephemera is hot these days, as is death, oddly enough—see the rise of the #deathpositive movement—so mourning artifacts are in high demand. Vintage tear catchers, also called “lachrymatory bottles,” can be found in online auctions and marketplaces, as well as through estate sales and antique stores. During the 19th century, and especially in America during and after the Civil War, supposedly, tear catchers were used as a measure of grieving time. Once the tears cried into them had evaporated, the mourning period was over. It’s a good story—too good. In truth, both science and history agree, there’s really no such thing as a tear catcher. Caveat emptor.

“People ask to buy them all of the time. At least a few people a week,” says Christian Harding, owner of The Belfry, an oddities and collectibles store in Seattle. Harding then must explain that the bottles most are looking for—blown, usually clear, glass decorated with patterns, gilding, and colorful enamel—are throwaway perfume bottles. But the “tear catcher” term has stuck, through a combination of historical accident and deceptive, yet effective, marketing.

The myth likely began with archaeologists and an oddly chosen term. Small glass bottles were often found in Greek and Roman tombs, and “early scholars romantically dubbed [them] lachrymatories or tear bottles,” writes Grace Elizabeth Arnone Hummel, who runs the perfume website Cleopatra’s Boudoir. Those glass bottles held perfume and unguents, not tears, Hummel explains. “Scientists have performed chemical tests on these flasks and they disproved the romantic theory.” But stories sometimes acquire their own momentum.

Nathan Graves, owner of Cemetery Gates in Portland, Oregon, first stumbled across tear catchers while researching mourning jewelry. He was suspicious immediately, because the bottles look identical to ones he’d seen in antique shops, flea markets, and yard sales for as long as he could remember. “Always thought of them as grandma’s perfume sample collection,” he says. “The idea that people were collecting tears in them seemed like folklore.” The terms “Victorian” and “mourning” in general, Graves continues, have become catchalls for anything old, sentimental, or made of black materials. “I think some people have the tendency to romanticize objects and their history.”

“It’s a beautiful idea but no one really [cried into the bottles],” Harding agrees. “Through the years, after reading many different articles and speaking with other collectors, I realized that the stories were, in fact, just myth.” When asked about tear catchers by collectors eager to add Victorian curiosities to their wunderkammers, Harding explains the true uses of the decorative bottles, but many customers don’t want to believe it—and some just don’t care.

“I have probably sold dozens at this point,” says Katie Kierstead, owner of an online Victorian antique shop. She “fell in love with the poetical conceit as much as anyone else,” she says. She did her research and regularly stocks them—in the perfume section. “They are worth the same amount to a perfume bottle collector as to someone interested in mourning,” she says.

Not every seller is so transparent, which helps the tear catcher tale persist. Much of the online information that still links the bottles to the mourning story can be traced back to Tear Catcher Gifts, a company that sells modern tear bottles intended to be given as gifts at special occasions. The startlingly uncritical “tear catcher” article on Wikipedia, at the time this story appears, lists only two sources: the website of Tear Catcher Gifts, and another registered to a Tear Catcher email address.

According to a 2004 article in Belgrade News, the owners of the largest wholesale distributor of Tear Catcher Gifts’ modern bottles, Timeless Traditions, were inspired by the 1996 bestselling novel Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood, in which a character gives her mother a lachrymatory. “I looked everywhere [for them],” coowner Jacqueline Bean told Belgrade News. “[I] found no bottles but I did find all these women who had read the book and were looking for them too. … Our goal was to saturate the market as quickly as we could to keep competition at bay.” The bottles are available at dozens of stores, both online and off, and several “informative” sites appear to exist entirely to drive customers to purchase them.

“That’s why I think it’s important for academics to engage in public discourse,” says Nuri McBride, a perfume collector and researcher who writes about the intersections of fragrance and death rituals at Death/Scent. “The Internet is, in a lot of ways, its own folklore-creating machine,” she says. “If a unit of data gets shared enough times it is considered true.

“A cosmetic historian or a Victorian glass expert could have told a customer in 30 seconds [that] those bottles are not lachrymatories and the colorful eBay descriptions of Civil War brides were spurious at best,” she continues. “But we need to be in a position to interact with each other for that to happen.”

Harding, owner of the Seattle oddities store, hopes that such interactions will happen more often as more people become interested in collecting Victoriana. “Over the five years [my store] has been open, it seems like the situation gets worse,” he says. He continues educating customers, as do Graves and Kierstead. One of the Tear Catcher Gifts sites takes a more untroubled approach to facts: It states that the scientific truth will be uncovered eventually (it already has), “but until then, each of us can choose our own belief.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook