The Exit Interview: I Spent 12 Years in the Blue Man Group

Three Blue Men, one Isaac Eddy (middle). (Image courtesy of Isaac Eddy)

Welcome to the the first in a new series of Atlas Obscura features known as the Exit Interview. In these features we will be speaking to people who have held the world’s most interesting jobs, finding out why they chose their unique path, what it was like to live it, and ultimately, why they chose to leave it. Have a story? Let us know!

Blue Man Group is a theatrical performance that defies easy categorization—part drumming, part acting, part Tobias Fünke—known for an audition process that competes with Manhattan preschools for difficulty of acceptance. But what’s it like to be behind all that blue paint? We spoke to a recently-retired Blue Man named Isaac Eddy. For over 12 years, Eddy lived and performed behind the thick blue veneer and anonymous black garb of the Blue Men. From Las Vegas to New York to London, Eddy portrayed one of the wordless azure elementals first developed by performance artists Chris Wink, Matt Goldman, and Phil Stanton in 1991.

In our conversation with Eddy, we found that he was far from silent about his experience as a Blue Man. From the struggles of learning drumming for the audition, to how the behavior of dogs informed his performance, to his portentous final show, Eddy let us in on just about every aspect of his time under the Blue, and why he decided to be a human again.

The Making of a Blue Man

You were with the Blue Man Group. How did you get into that? What was the lead up to you joining the Blue Men?

I studied film in undergrad. I always did a lot of performing there with this long-form improv group, and in plays, and film. But I was thinking more of career stuff being filmmaking. So I moved to LA after school and lived there for a year and a half, and was really missing live performance. I saw footage of the Las Vegas Blue Man show, and I looked them up and saw that they had an open call in a couple of weeks, so I just drove out to Las Vegas and went to an open call. A lot of people who end up doing the show felt like I felt, where I just understood the character and wanted to get into it. I wanted to understand the character from a performer standpoint. I just intuited it by watching clips of the show.

But I needed to work on my drumming so I just practiced drumming for nine months with a teacher in LA, to do a second audition, and I was called to train in New York after that.

So you didn’t come at the role from a musician’s perspective, but from a performing background.

I have always played music. My mom is a musician and I grew up playing piano, and french horn, and singing, and have always thought of myself as rhythmic. But I never trained with drumming, so I definitely had to get my chops up on the musical end. So it was definitely from an acting standpoint that I was drawn to it.

So what was the audition process like?

It’s evolved slightly throughout the years because it’s tough to find Blue Men. About half of us are professional musicians who learn the character, and the other half are professional actors who learn the music. The thing that’s hard is that the character is not the kind of character that a trained actor can immediately understand, and that’s why half of the Blue Men we have aren’t even trained actors. It’s a ‘clown’ character for all intents and purposes, which is a term that’s kind of misused now. For the character to be believable it has to tap into an honesty and a sense of self that a lot of times, actors are trained to get rid of. There are some people who can access that honesty in the character, and there are other people who are basically trained in all sorts of acting styles that can’t really access it.

The audition process is set up to see who can access that and who can’t. [It is also set-up to see] who can tell a story without using any words, but also without being melodramatic, and without over-acting. Just this kind of pared down simplicity, with not much physical movement, just able to express these simple, base emotions, just with your eyes basically.

The audition is half-character-work and half-music. You have to be able to get at least a decent part of the music. A lot of the training process is learning drumming, or learning the Blue Man style of drumming. If you don’t have that elemental understanding of drumming you can’t really get the gig. In the [acting portion of the] audition process there are these different techniques that have been taken from Meisner, and Grotowski, and from simple acting, and been tooled to specific Blue Man purposes. [In my audition] I was given this simple task, which is just, entering the room. It is an old, old clown exercise. You enter the room as a neutral character, just trying to be as pared down, and as honest as possible, just taking in the people in the room. Then you leave the room once you feel something has been exchanged between the two of you. This exchange can be something monumental like we discovered the meaning of life, or we cured some huge disease, or it can be very, very tiny, just a simple hello. Just an exchange of a greeting or something. Simply by doing a very pared down audition like that you can tell who is game for the complexity of the character and who isn’t really willing to go there.

Part of the Blue Man Group is a kind of homogenous anonymity. There are always three, but does each Blue Man have a specific motivation or character, or is the idea that they are all sort of, of a piece?

There are two parts to the answer. The first part is that we initially learn a single role of the three roles, and that single role was originated by one of the three founding members, Chris, Matt, and Phil. The three of them based their specific roles very specifically on their own personalities. So there is one character that’s much more of a trickster, there’s one character that’s much more of a team-focused leader, and there’s one character that’s much more of a mad scientist or a shaman.

When you initially learn a specific role, you are accessing that trickster, or that energy more than the other characters, but when we get down to it, we really are training one single character. The character itself has these contradictions, or modalities as we call them. You can be a trickster, but also you are completely egoless and focused on the group. You can be a shaman and also be a hero, or you can also be an innocent. What you have to learn soon in the training process is how to honestly access those modalities, but then be able to switch between different ones with ease. Not in this put on way. Not by puffing out your chest to be a hero, or slumping over to be a mad scientist, it’s more accessing it through these more honest ways, through your eyes.

The last part of it is you’re not just learning how Chris, Matt, or Phil did their own Blue Men. You have to also learn how to put your own bent on it. So each time you see the show, you are seeing three performers who have developed their own sense of Blue-Man-ness. There’s definitely a framework that you have to play in, and there are things physically that a Blue Man just does not do, and choices that a Blue Man just does not do. But within that framework, you have to find your personal take on it otherwise it’s just not that real. That’s basically true for all theater and all acting, but that’s the core to why there’s so many guys who have done it for so long, like me. You were demanded of a very creative input every single night that isn’t necessarily demanded of someone doing another musical or something.

Drumming is clearly an important part of being a Blue Man. (Gif by Hajohinta on Tumblr)

Life As A Blue Man

In a given production, how many Blue Men are there? Are there just three leads and a couple of stand ins or are there 20 guys who rotate in and out?

In the smaller shows there is typically seven full time guys. In the bigger shows, like Vegas, there are upwards of nine guys full time. The reason is because we do so many shows. In New York, the typical Broadway run is eight shows a week, and we will often do much more than that. On a slow week we’ll do 12, and on a high week we can do upwards of 20. So we need those extra guys to do those shows. This is also another reason why guys stick around for so long, because there is less of a grind that way. There will be slow weeks and you can take leaves of absence to do other artworks. Its just a much more stable, supportive environment that way. And for a theater gig… it was 12 years with 401K, full benefits for me, my wife, and my kid, a really stable setup.

Are there any Blue Women?

There was a Blue Woman once in Boston, and we still audition women regularly. It’s doubly hard to find women for the role simply because of body sizing making the talent pool that much smaller, but I hope it happens again.

What is the general tenure of a Blue Man?

Realistically, a little over six years maybe. Each cast is different. In the New York cast, there was a guy going on 18 years, a guy going on 16 years, another guy going on 15 years, then me, and guys below me going on 9-10 years. So it’s a real veteran cast. And then there’s guys who just finished training. It’s not always a tenure track thing where once you get in the only way out is being fired. You have to be able to find the newness in doing the show. Otherwise you are going to wither and die. You can’t just phone it in. You can’t just take a year and do the same show.

That’s when you’ll have a sit down with local management. We have this team of directors that work really closely with each show, and you’ll have a talk with them, and they’ll say, ‘How can we get back engaged with the show?’

Are the original three still performing?

I think the last time they officially performed was when we put the latest new material in which was about five years ago, and they did a big benefit show. And that was maybe the last time the three of them performed together. But they are heavily involved in directing and writing new material still. That’s kind of a key to the show is that they have a team. I was part of the writing team. They are always, always, always writing new material.

How much of a role did you have in the writing of the show and the invention of the contraptions?

I remember when I first started the show, I thought it was a literal art movement. Where, the people who were onstage were performing the part of the show that they created, and it was this new collaborative identity of what art is, and what art can be. With this weird strange character.

The truth is that it is much more like an old school production than that. There is a beat sheet, and there are straight pieces that are done every single night, and those pieces were created by the original three guys and some other people, and were tools for a long time, and were tested, and worked on, and everything. I was primarily an actor during the show.

That said, they know that the people who understand the character the best are the guys performing the character every single night. We know lands and what doesn’t, we know what audiences are responding to, we know what FEELS right as a character. So we are used as a sounding board and also as a creative resource all the time. There’s been musical pieces that have been written by [acting] Blue Men, there’s been small bits during the show that were thought of by Blue Men, and there’s been bigger picture things that were originally pitched by Blue Men. Relatively recently, in the last three years, they’ve set up this writing group that’s performer based. It’s about six of us that get together every single week and on our feet, improv new ideas brought to us by Blue Man Productions or brought up by the group itself.

Onstage, how much room for improvisation is there?

If you see two shows back-to-back, most nights I would say they are going to be more similar than not. But at the same time, there is room for improv, in that the audience itself is the fourth character of the show. That’s a really important part of the show. The show opens with us looking out to the audience and expecting something from them. And we don’t get it. We’re expecting this connection between the audience amongst themselves, but also from us to the audience. We basically spend the whole show trying to create that tension that we thought we would have at the beginning of the show.

We as actors are literally looking out to the audience, and the feedback we get from that is different every night, and that translates to the tenor of the show. There can be times where there’s this real raucous, screaming audience and the Blue Man responds differently to that than to a sleepy matinee audience, or to a kids audience, or a thoughtful audience, or one that is kind of nervous about the character. So there is improvisation in a smaller way based on that.

Basically there’s a thing we talk about, which is kind of good Acting 101, which is ‘good news or bad news.’ What’s great about the character is that every quote-unquote line of the show can be either good news or bad news depending on the energy of the night. That’s where the minutia improv comes in. Being able to take stuff in real time, based on the different actors, different musicians, and different audience. That being said, we are highly, highly trained in improv. That’s a real valuable part of the show. That audiences have this idea that they’re seeing something that’s only happening that night. You can learn the show beat by beat, but if you can’t inhabitat a Blue Man naturally in an improv situation, then you’re not really doing the gig.

That comes into play when there are big technical problems with the show. We stay in character unless our safety is at risk, and no matter what happens, the audience almost always thinks it’s part of the show. Because we know how to react to it.

What is the overall story that the Blue Men tell? Are they aliens? What are the Blue Men?

There are definitely different ways to look at it. In training and talking about it, we’ve specifically never allowed ourselves to land on one single answer. What I like to think of it as is that we’re these beings that are summoned by the audience itself. Who is the guy who talks about the different masks?

Joseph Campbell.

Exactly. So it’s this Joseph Campbell psychological analysis of the audience itself. So the Blue Man is reflecting the audience itself and the Blue Man is summoned by the audience itself. A primordial, psychological journey of the audience itself. Put more simply, you could think of it as, the color blue. It’s cased off that Yves Klein blue. That bright, bright cobalt that he created himself, and that he covered [a series of objects and paintings] with and nothing else. So the concept is that we emerged from a painting like that. Like our primordial soup is from the art world, and we are summoned by the audience to connect them and free them from this urban isolation. To have this single moment of connection.

International Klein Blue, the real color of the Blue Men. (Photo: Wikipedia)

What are the beats of the day in the life of a Blue Man.

A normal day is an 8 p.m. show, and your call time is an hour, hour and a half before that. So you show to the theater, let the stage manager know that you’re there.

Then you do warm up, and the warm ups are different. For some guys, it’s really just coming into the room and talking to everybody, seeing where everybody’s at, joking, talking about the news. For others it’s a hardcore workout; push-ups or yoga or that sort of thing. For a lot of guys it’s drumming. Get out the drum pads, and get the metronome on, and get the blood flowing, get the kinks of the day out.

Soon after that it’s sound check. There’s a lot of set up in the show that’s different than a lot of other professional theaters in that there’s a lot of times in which we circle up and see everybody who is working on the show that day. That’s something really important that was set up by the original guys and the original crew and the original band, that I think is really valuable. We all stand on stage and that’s the first time we see the band that’s in that night, and the stage manager, and the crew, the electrics, and video and sound. We ask if there’s anything specific that we want to work on. If there’s something specific we messed up the night before, you might want to see it or brush it up or something. Otherwise there’s this normal lineup of songs we play every single sound check so that the sound person can make sure that the sound is right that night. Then they test all the video cues and everything. Its a great way to have a connection that night with the band. To learn where you are with the metronome that day.

We practice throwing and catching, which is a big technical part of the show. Catching stuff in our mouths, and getting used to the distance with the throwing and everything.

Then there is about an hour after that to get the bald cap on. This is a really important time to connect with the Blue Men and with the wardrobe person. The wardrobe person is a very valuable part of the pre-show ritual, and we are very, very close to our wardrobe people, in the way that we talk with each other before the show.

And all this, you might see it as just people hanging out at work and having fun, but it is definitely a ritual. Us shedding our adult duties, and our adult responsibilities, and all the things that weigh us down in the day. I’ve really fought for this hour and a half of freedom from that. In this hour before the show you’re slowly getting all of that out of yourself, and giving yourself the privilege and freedom and opportunity to inhabit this playful character who doesn’t have those issue.

Can you tell me a little bit about the make-up process?

There’s a special bald cap that goes over the ears. Then there’s this old school grease paint that we put on thick on our heads. Then after the make-up process, we have [a meeting], which is the last time we meet up with everybody. We meet with the whole crew and the band backstage and talk about the different groups that are coming to see the show that night, but we also talk about the different performances and gallery openings and different shows that everybody in the cast and crew are a part of, so that everyone can go and support each other outside of the show. Again, there is this tribal connection in recognizing that the show is so far beyond just the three guys on stage. Theres about 15-25 people in the room at that point.

After that we finish with the wardrobe person, getting our make-up on, getting our costume on. At that point its about right on the hour and we are doing the finishing touches while the audience is getting seated. Getting ready to go on stage.

So then you go and you ‘Blue Man.’ Afterwards, what is the teardown process?

So immediately after the show, we go and clean up a little bit. And this has been a really important part of the show since the beginning, we go and meet the audience as they’re leaving the theater. That’s a really special part of the show too, or one that I’ve always enjoyed because you can shed the character slightly. We always talk about that it’s 80 percent Blue Man and 20 percent just yourself at that point. So if someone comes to you and says, ‘That show meant so much to me,’ you can very quietly say, ‘Thanks a lot.’ We’re not the hardcore character in that moment even though we’re still in make up.

The point of that part is so that the person right next to you can have that connection, but the person across the room still just sees a Blue Man. It’s not like we’re there with our arms swinging, and smiling, and with our teeth showing, we’re still inhabiting the image of the character. What I love about that part of the show is there’ll be shows where I felt like it didn’t land. Where it was really quiet, the audience seemed sleepy, and didn’t really connect with us, and then we’ll go to meet and greet, and they are just blown away. It’s nice to have that as a reminder that just because we think a show wasn’t that good, it doesn’t mean that it didn’t resonate for them.

So that’s about 15-20 minutes. Then we go downstairs, and as we’re getting out of makeup, in this other important Blue Man tradition, we have about a 20 minute conversation with the stage manager of the night and the band. We talk about all these different parts of the show. And this is why, again, that guys can stay in it for so long, because it is always, always, always considered a work in progress. There’s always stuff that can be done better. Just because there’s a guy who’s been doing it for 12 or 15 or 16 years, doesn’t give them any kind of ‘Get Out of Jail Free’ card. We’re working on stuff day-to-day just as much as trainees are basically. Maybe it’s a little bit more on a smaller scale, maybe the mistakes are smaller, but it’s similar stuff. That right there, that 20 minute conversation is how the show can sustain itself. Because after training, a Blue Man doesn’t have daily contact with directors, so after training, it’s those discussions that are teaching new Blue Men how to approach the show. So if you don’t engage in that conversation, that’s teaching the new guys that that’s not what it’s about. Especially in the last couple years we’ve been training how to communicate, and how to give notes in a way that isn’t authoritative. Legitimate, flatline collaboration. So me saying stuff like, ‘You were off in this part of the show,’ we’re trying to say it not from a point of authority, but from a position of, ‘I make mistakes too, please bring them up.’ It’s that hard, hard direct democracy type of thing.

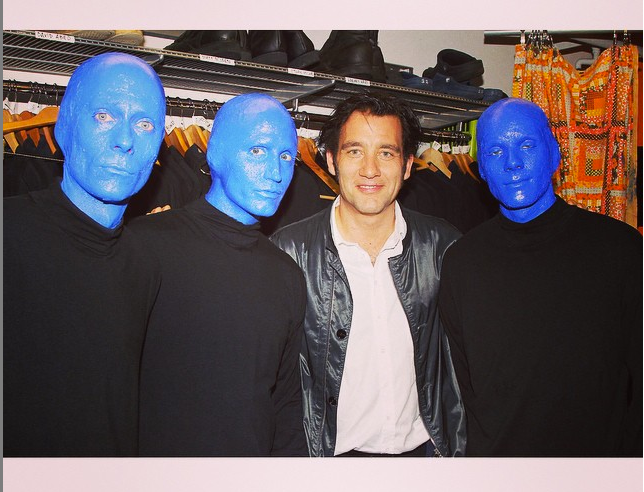

Isaac (on the far left), with Clive Owen. (Image courtesy of Isaac Eddy)

And all of this is happening while you’re still in makeup.

Yeah (laughs). It’s the sort of thing that looks so normal to us, but if you took a snapshot of it, it would look so, so strange.

So after that you, somehow, de-makeup?

Yeah, we use jojoba oil, and other oils, and it just cuts through the makeup under hot water and a towel. It comes off easier than you think. It’s funny, in the scheme of the show I never thought about it, but now that I’ve been away for a couple of weeks, the thought of putting that on my face? Nonono.

Did you find that it just got everywhere?

You very quickly learn how to curb that. Because we have to touch up our heads all the time, and you just know which fingers on your hand have a little bit of Blue. You just don’t touch things with those fingers and you know when to wipe it off. And you never, ever, ever touch your head to anything. You just think of yourself as having a three-foot forcefield around your head.

The Rules of Being Blue

What are the rules of being a Blue Man in terms of what you can talk about out of character, and when you can talk in character and so forth? What are the ten commandments of being a Blue Man?

With the performance you have to stay engaged and you have to learn how to continue to access an honest engagement with each moment of the show. And you have to listen on a higher degree and to more elements in each moment than is humanly possible. Atune yourself like an animal. Listen more than you have ever listened and focused before.

You have to learn how to react in an egoless way, that’s really crucial. Let’s say an audience member is using their phone, just like five feet from you, filming you. An actor reaction is like, ‘Hey, you’re messing everything up,’ but a Blue Man reaction is more like, ‘Isn’t that interesting that that person is holding this in my face?’ You learn how to kind of continue to skew your perspective to take out the ego.

On engagement, you have to know the script, and be willing to go on the script wholeheartedly, but have the confidence if the moment calls for it. That’s something that’s really hard to figure out. Especially because you do the show so much that you could just ignore something. Let’s say an audience member makes a funny sound. You could just ignore it and the show would move on and finish and we’d be done. But if you recognize it, that adds other elements of liveness to the show that’s so important. So just be willing to go off script and know how to make choices as a Blue Man, and stay in it that way.

In terms of decorum, for instance you guys can’t speak, what are the hard rules?

There’s a lot of physicality work. A lot of that is pared down movement. We talk a lot about how dogs approach the world. An excited dog will do anything, but if you think of a dog on the prowl, there’s no waste of movement, there’s no excess movement. A dog can be very carefully walking up behind a squirrel and there is an intensity, but not in muscles. So how to access that hard intensity without face tension, without clenching your jaw, without flexing your muscles. But having this open chest, and this open heart, and this deep intensity without overdoing it in those ways.

The same goes for your arms. Your arms need to be in a neutral position and at your side, but also not look slack. That’s basically a lot of the physical elements of the character. You need to be neutral but not relaxed. You need to be intense but not tense. There’s all these things you have to inhabit, but you can’t do it in the natural way.

The similar with the drumming too. There’s a real physical element in the drumming, but you can’t physically do it the way that it looks, otherwise you won’t last for a year in the show. You’ll get carpel tunnel. You’ll mess up your nerves by staying tense and drumming that way. You learn how to be completely relaxed with the drum stroke, but still have it look like that intense Kodo imagery.

If you are looking at it something, you want to square off to it. You don’t do a lot of simple head turning or simple eye turning. You turn your shoulders to something when you look at it. But at the same time, you don’t want to look stiff, cause then it looks like you’re wearing a neck brace.

The thing that is so cool about the character is that you definitely see a stylized character, but it’s also so pared down and simplified that you can’t really see what the stylized elements are. So when you see a school assembly versions of the Blue Men, like people doing Blue Man performances in a high school, just doing these impressions of the Blue Men, you can immediately tell that it’s something else. That it’s not what we’re doing. Typically it’s because the arms are sticking way out from their hips, and there’s just this weird kind of overstated movement that we just don’t do. But when you see the show, and you go home and think of the character, you’re thinking of us doing that thing. When [someone] looks back at me and tries to do a Blue Man impression, they always pop their eyes super-duper wide, when really we’re not popping our eyes like that. It’s simply that we’re looking so intently that people think we’re doing that.

Out of character, what are the rules of being a Blue Man? In terms of what you can and cannot talk about and so forth?

Typically with interviews, it’s primarily about the show. You run it by the [production] to make sure it’s cool, like I did with you. There’s some kind of old school secrets about the show that we don’t talk about. What I love about the ‘magic’ or ‘tricks’ of the show is that it’s really Vaudevillian. We want you to think that we don’t want you to know it, but you do in fact know it. In some ways you can then have a bigger trick a little later on. Basically that old school thing of thinking that you’re knowing what’s going on more than we as performers think that you know. It gives a little bit of excitement. Like you’re outsmarting the show.

We don’t talk out and out about how much we get paid. We don’t get into great, great detail about the makeup process. I think that’s pretty much it.

The Blue Men perform with Amanda Palmer. (Image courtesy of Isaac Eddy)

Leaving the Blue Men

So let’s get to why you left. Why did you leave after 12 years?

I was thinking a lot, just like everybody does with your career, what I wanted to do post-Blue Man. What was my ideal set-up. It became pretty quickly, way less about getting other acting gigs, and way more about shifting focus entirely. That primarily came from [a feeling that] I wouldn’t be as fulfilled in any other acting gig as I was with Blue Man. I also really appreciated the stability of it. I’m the kind of person that is very, very creative when I have stability. All the times, like when I lived in LA and at other points when I was unemployed, thinking that I had all this time to do everything, I just didn’t do anything. So if I left Blue Man and just did freelance acting… I’m just not cut out for it. I’m just not interested in that.

A few years ago I picked up cartooning, which is something I’ve done my whole life, but I took it more seriously. I started doing animating, I got a few cartoons in the New Yorker, and I got a small web series picked up for a little bit. I was thinking that that would pretty interesting to work more on after Blue Man.

Soon after that I started teaching at this art institute for high school students up in Vermont, where I’m from. I started to realize how much I love teaching. Everything I loved about acting I got back tenfold from teaching.

Because of doing that over the summer, I looked into MFA programs that I could do while I was doing Blue Man. It was that kind of scary dance where I didn’t want to up and leave because I still was loving the show, and I didn’t even know if wanted to start a new career. But I was also wanting to do something new.

So I found this MFA program at Brooklyn College, that’s performance and interactive media art. It was this beautiful thing that combined everything I’m interested in. With cartooning, and with computer programming, and with performance art. Luckily I was able to do the two-year program while I was working at Blue Man. It was a testament to both institutions that I was able to do that. And to my wife too. Just biking all over the place. It was a crazy two years.

I felt like, okay, I have that under my belt. I could teach university-level theater, or performance art in the future, but I can also just have that for future works. I allowed myself to leave it at that and not go crazy trying to find other work. But then, my wife grew up on a farm in western Massachusetts, and I’m from Vermont, and we were starting to think more and more about our kid having some of that woods life. Just being able to be alone in the woods for ours and not having us hovering over her for fear of being hit by a car or something. We started thinking more about a move back up to some place a little more rural. Randomly I heard about a full-time theater position opening at Johnson State College in Vermont. It’s a small program. There’s only one full-time theater professorship. I applied, and went up for interviews, and got offered the job. So I took it.

When did you leave the Blue Men?

My last show was June 2nd [2015].

What was your last show like?

There is kind of a Blue Man tradition on last shows to commemorate it in such a way that the audience doesn’t know anything crazy is going on. But we can tell that there’s small things throughout the show that are kind of a commemoration. There’s a lot of things slipped in as goodbye pranks to me.

There’s a part where the Blue Man is supposed to be eating Captain Crunch, and they cut up orange cubes of cheddar cheese to look like Captain Crunch. Which is classic Vermont cheese. I’m stuffing my mouth with what I think is Captain Crunch, but it’s cheese. There’s parts where you’re supposed to rinse your mouth out after different parts of the show, and they filled up my cup with maple syrup. There were little hidden pictures in different parts of the show. It was really beautiful.

It was intense for me, because I probably will do the show again in some capacity, but I probably won’t ever have the camaraderie that I had with this cast. There is a real saying goodbye to something that’s really important to me.

The craziest thing in my last show, there was a kid in the second row, and the last part of the show is an intense, amazing dance party connection with the whole audience. This teenager had a seizure. In the end he was fine. It was a mild one and he totally was fine. But what was scary was that he had never had one before. So in this moment that is supposed to be elated and celebratory, I’m the only person working in the theater who looks down, because he was in my section, and saw that he was having a seizure. So I left the stage to tell front of house, that they should call 911. People thought that I was leaving the stage as this kind of home run lap celebration, high-fiving everybody down the aisle. Really I was trying to help out this kid. A chaperone from the group stood up when I got back on stage, and was like, ‘Stop the show!’ It was this moment of saying goodbye to the show and this scary thing, happening all at once. It put it into perspective. That it wasn’t just about me.

What’s your final statement about being a Blue Man?

The thing that I learned that had the most value from doing the show, is the true power of listening. The power of being silent. And in terms of storytelling, what that creates in a room. If you have a character that’s silent and listening there’s all of a sudden all of these complexities in that character that you didn’t necessarily think of in the initial creation of the character.

For my life, how that’s changed me, is being comfortable with not knowing everything. Being confident enough to allow yourself to continue to listen and learn from others. Basically the confidence in the egoless choice to listen and learn.

And also an appreciation for blue paint.

Definitely.

Isaac Eddy, blue no more. (Image courtesy of Isaac Eddy)

This interview was edited and condensed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook