The Beautiful Network of Ancient Roman Roads

A Roman Milestone from the Via Romana XVIII, which connected Bracara Augusta to Asturica Augusta. (Photo: Júlio Reis/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

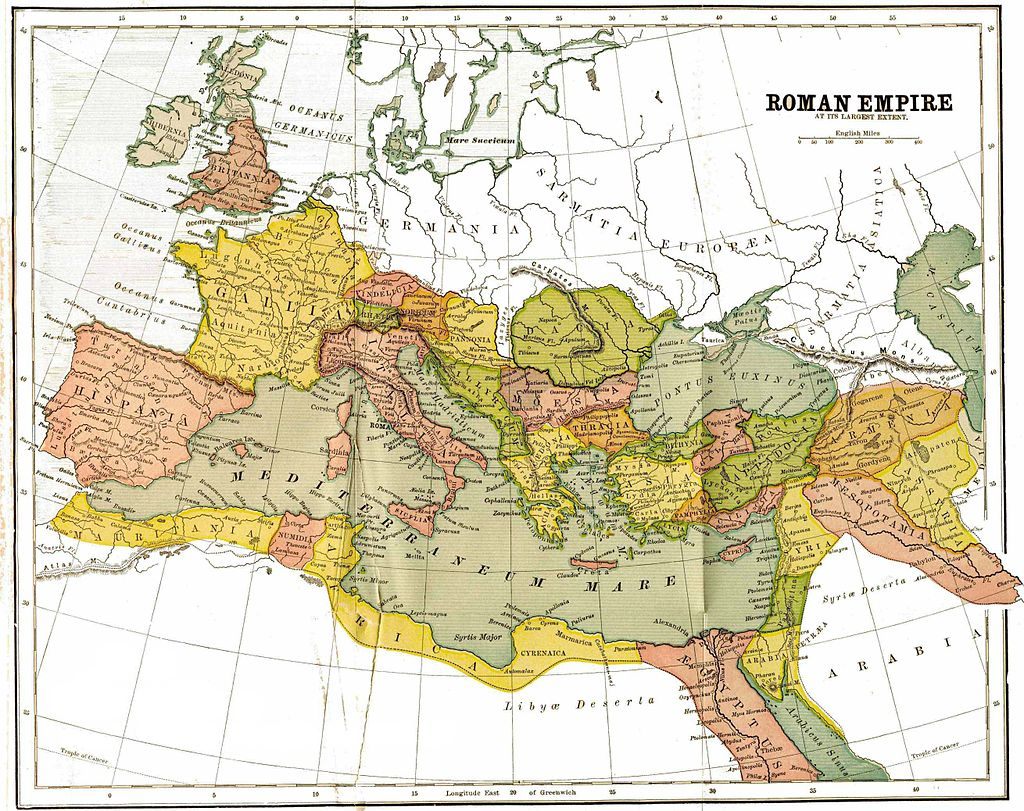

In today’s terms, it’s hard to fathom how much of the world the Romans once controlled. At its peak, the Roman Empire spanned from Hadrian’s Wall in Scotland to Morocco, from the banks of the Rhine River bordering Germania, to Egypt, and east to the Euphrates River in Mesopotamia—a huge swath of conquered peoples and occupied lands, with barbarians on the borders.

Thousands of years later, monuments of Roman glory and imperialism still stand throughout Europe. Huge concrete buildings like the Colosseum remain, as do stone plinths and obelisks.

But the Romans’ most impressive achievement, and most important contribution to modern Europe, lies underfoot.

A Map from 1897 showing the Roman Empire with provinces, in 150 AD. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

A Map from 1897 showing the Roman Empire with provinces, in 150 AD. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Roads, built to allow the empire to flow outward, and for the rewards of empire to come flooding back to the capital, were the key to the Romans’ governance of Europe. Along these roads ran messengers, as a type of precursor to the American Pony Express—a relay of horsemen could carry a message 50 miles a day. Governors, emperors, legions, and, most importantly, trade flowed along these ribbons of stone that cut through hills and across gorges. In 9 BCE, the Emperor Tiberius rode almost 215 miles along the roads in 24 hours to get to his dying brother’s side. For a small toll, other, non-official travelers could travel the roads as well.

Inside the Colosseum, Rome. (Photo: Philip Capper/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

Roman roads are still visible across Europe. Some are built over by national highway systems, while others still have their original cobbles—including some of the roads considered by the Romans themselves to be the most important of their system.

Via dell’Abbondanza in Pompeii (Photo: Mentnafunangann/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

One major road you can still visit is via Appia, or Appian Way, the most strategically important of the Roman roads. Begun in 312 BCE, the road runs from Rome southeast to the coastal city of Brindisi, a distance of 350 miles. It was via Appia that allowed for the Roman conquest of southern Italy, and the defeat of the Greek city-states and colonies embedded there.

The Appian Way was host to battles between the Romans and the Greek general Pyrrhus from 280 to 275 BCE, which is where we get the term “Pyrrhic victory:” a victory that comes at too high a cost. Via Appia was also the site where, in 71 BCE, around 6000 members of Spartacus’s slave army were crucified on the hillsides.

The road also has more recent military history—it was the site of the 1944 Battle of Anzio during the Second World War, in which the Allies became mired in the same swamp that threatened to fell Pyrrhus two millennia earlier.

A Map showing the Appian Way and the shorter Via Appia Traiana. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

A Map showing the Appian Way and the shorter Via Appia Traiana. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

In France (Gaul) and Spain (Hispania), the road systems were no less impressive than in Italy—the Alcantara Bridge, over the Tagus River, was built in 106 AD, and carries the inscription “Pontem perpetui mansurum in saecula,” or “I have built a bridge which will last forever.” This is not strictly true. While the bridge still stands, it was damaged, first by Moors in 1214, then by the Spanish in 1762, and again in 1809. There are, in fact, two bridges in Spain named Alcantara, built by the Romans, and a third, similarly named bridge, the Alconetar Bridge—all of which span the Tagus, in Western Spain. The word “Alcantara” comes from the Arabic word “al-qantarah”, which means “bridge”.

The Alcantara Bridge across the River Tagus, Cáceres Province, Extremadura, Spain. (Photo: Dantla/WikiCommons)

The Romans also acquired roadways and Latinized them—the via Domitia, which ran between Italy and Hispania through southern France, was an ancient path that the Romans paved in 118 BCE. Prior to the Roman upgrade, the path featured in Greek mythology as the legendary route of Heracles when he drove the cattle he stole from Geryon along it. This road was also the one travelled by the Carthaginian general Hannibal when he invaded Italy in 218 BCE. Along the via Domitia lie the remains of two bridges, one of which, the Pont Julien, is passable to foot traffic. The other, the Pont Ambroix, is ruined but beautiful.

Pont Ambroix. (Photo: Xabi Rome-Hérault/Wiki Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Along the Roman road via Julia Augusta, which also runs through the south of France, there are the remains of a number of bridges. The Pont Flavien is in the best condition, and is perhaps the most archaeologically important: it is the only surviving example of its kind of bridge, and was constructed as a funerary monument. It was heavily used until the end of the 20th century, and has been extensively repaired. Pont Flavien has sustained a lot of damage in the last few hundred years—part of it collapsed in the 18th century, and, during the Second World War, both a German tank and an Allied truck crashed into one of the archways. The bridge is now reserved for foot traffic.

Pont Flavien on the Touloubre river in Saint-Chamas, France. (Photo: Carole Raddato/flickr)

Pont Flavien on the Touloubre river in Saint-Chamas, France. (Photo: Carole Raddato/flickr)

The detail of a lion atop the Pont Flavien. (Photo: maarjaara/flickr)

The detail of a lion atop the Pont Flavien. (Photo: maarjaara/flickr)

Then there are the world famous archways of the aqueduct that crosses the Gardon River, the Pont du Gard. Built in the first century, the aqueduct and bridge stand in such good condition due to their being used as toll roads during the Middle Ages. Originally the bridge was used for vehicular and pedestrian traffic, but access is now restricted to pedestrians.

The vast Pont du Gard near Nîmes, France (above) and below, a closer view of the existing structure. (Photo: Oleg Znamenskiy/shutterstock.com)

The vast Pont du Gard near Nîmes, France (above) and below, a closer view of the existing structure. (Photo: Oleg Znamenskiy/shutterstock.com)

(Photo: Andrea Schaffer/flickr)

(Photo: Andrea Schaffer/flickr)

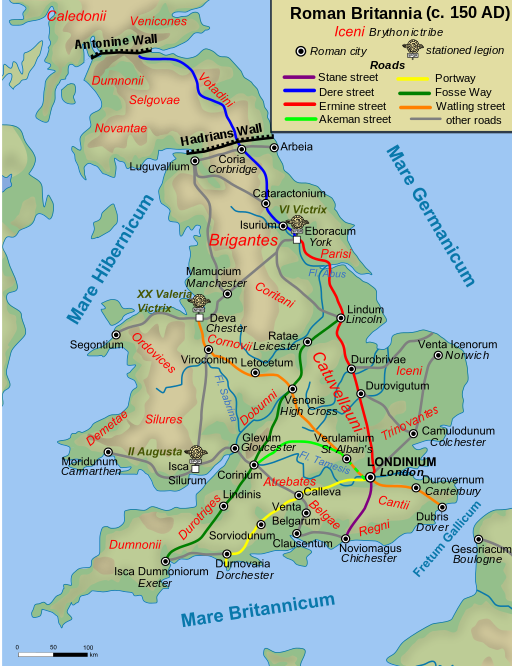

In contrast to Hispania and Gaul, the Roman Empire never made much headway into Germania. Much of the Roman road network in the former Britannia has been built over or has decayed. Beginning their work in 43 CE, alongside the invasion organized by the Emperor Claudius, the Romans quickly built a road network through the lands they controlled in Britain. Although parts of this network remained in place, most roads quickly decayed after the Roman withdrawal. Modern roads cover much of the network—an example is the M20 motorway in Canterbury, beneath which lies a road known as Stone Street. There are ruins of bridges still visible, such as in Northumberland, where parts of Hadrian’s Wall and Chesters Bridge can be seen, as well as in Durham, at Piercebridge.

A map of Roman roads in Britain. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Few roads remain in Germany, but the oldest still-standing bridge in the country is of Roman origin: the Manfred Bridge, in Trier. A UNESCO World Heritage site, the bridge spans the river Moselle, near the German border with Luxemburg. It is believed to date from the second century CE.

If we head east, through Dalmatia (modern Croatia) and Thracia (parts of modern day Greece, Bulgaria, and Turkey), we can travel Roman roads like the via Militaris, which ran from what is now Belgrade to what is now Istanbul. A section of the road is today visible in Dimitrovgrad, Serbia.

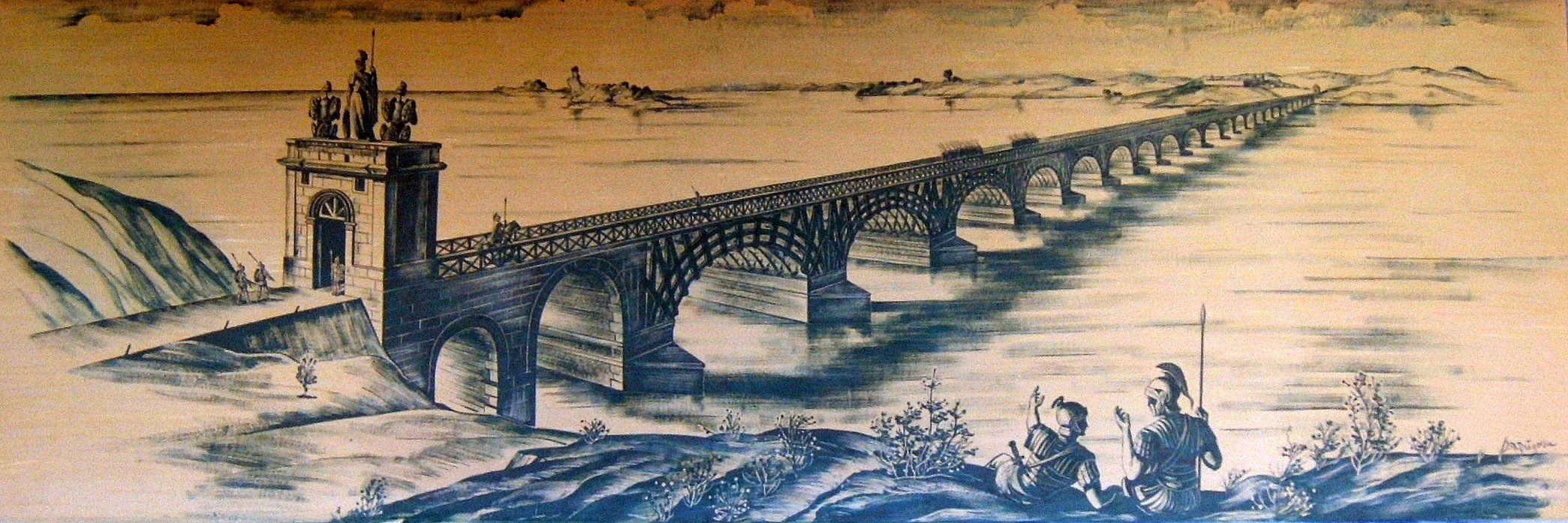

By taking the via Pontica you can see the craggy, ruined remains of Trajan’s bridge, which was built in 103 CE to cross the Danube in Romania. Much of it was destroyed by Trajan’s successor, Hadrian, as a precaution against invading hordes.

An artist’s interpretation of Trajan’s Bridge from 1907. (Photo: Rapsak/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

In Turkey there are still some Roman roads and bridges, like in Cilicia, or at Cendere Cayi, where the Severan Bridge steps 112 feet across the creek. Throughout Asia Minor and the Middle East ran a number of Roman roads, sometimes their own creations, other times imposed on top of existing roads. The via Maris (which translates to the “way of the sea”) connected Aegyptus (Egypt) with Syria, Palaestina Judae, Cappadocia and onto the rest of the Empire. It traces an ancient trade route that was in existence from the early Bronze Age, and was originally called the Way of the Philistines. The via Regia (later the via Traiana Nova) was also built on an ancient trade route—the King’s Highway, which stretched between Egypt and Damascus. The most well-known Roman road in the Middle East, however, was built in the first century, and leads to Petra, through the gates of the city.

(Photo: Dennis Jarvis/flickr)

(Photo: Dennis Jarvis/flickr)

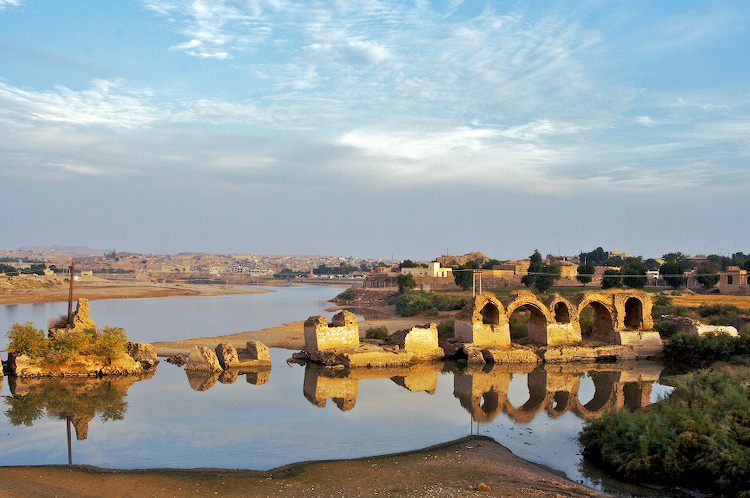

There are also a number of Roman bridges in the Middle East. Band-e Kaiser (Caesar’s Dam) was a Roman bridge and dam built by contracted Roman workers in the third century CE. It is the easternmost Roman bridge and dam, as Iran was, at that time, part of the Persian Empire, not the Roman one. According to legend, Shapur I captured the Roman Emperor Valerian circa 257 CE, and forced him and his army to build the dam and bridge. This is what remains of it now:

“Caesar’s Dam”. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

“Caesar’s Dam”. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook