The Hidden History of Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language

How a deaf utopia was uncovered in the 1970s.

Deaf children signing the Star-Spangled Banner in Cinncinati, c. 1918. (Photo: Library of Congress/ LC-DIG-npcc-33373)

In 1979 in the town of Chilmark, on Martha’s Vineyard, Joan Poole Nash sat across from her great-grandmother Emily Howland Poole, surrounded by a team of linguists and a video camera. “Do you remember the signs for rain or snow?” In response her great-grandmother moved her hands, which were recorded on grainy, black-and-white-tape.

The old woman continued: “This of course was marriage…and this was courting.” The room, according to transcripts from the interview, oohed and aahed. Poole Nash then interviewed her grandfather and others, but none were Deaf— they’d learned sign language as a natural part of growing up in Martha’s Vineyard prior to the 1950s. The entire area was once fluent in their own sign language dialect, though by the ‘70s, only a few speakers remained. On this island several miles off the southeast coast of Massachusetts, Poole Nash had uncovered a piece of Deaf culture and language that had been hidden for decades, and was almost lost.

For two centuries Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language (MVSL) was used by hearing and Deaf people alike, specifically in the Squibnocket part of the Chilmark area of the island, which was isolated by swamps and rocks. Due to inherited deafness, one out of every 25 people were deaf by the 1850s—compared with a national average of one in every 5,728 people.

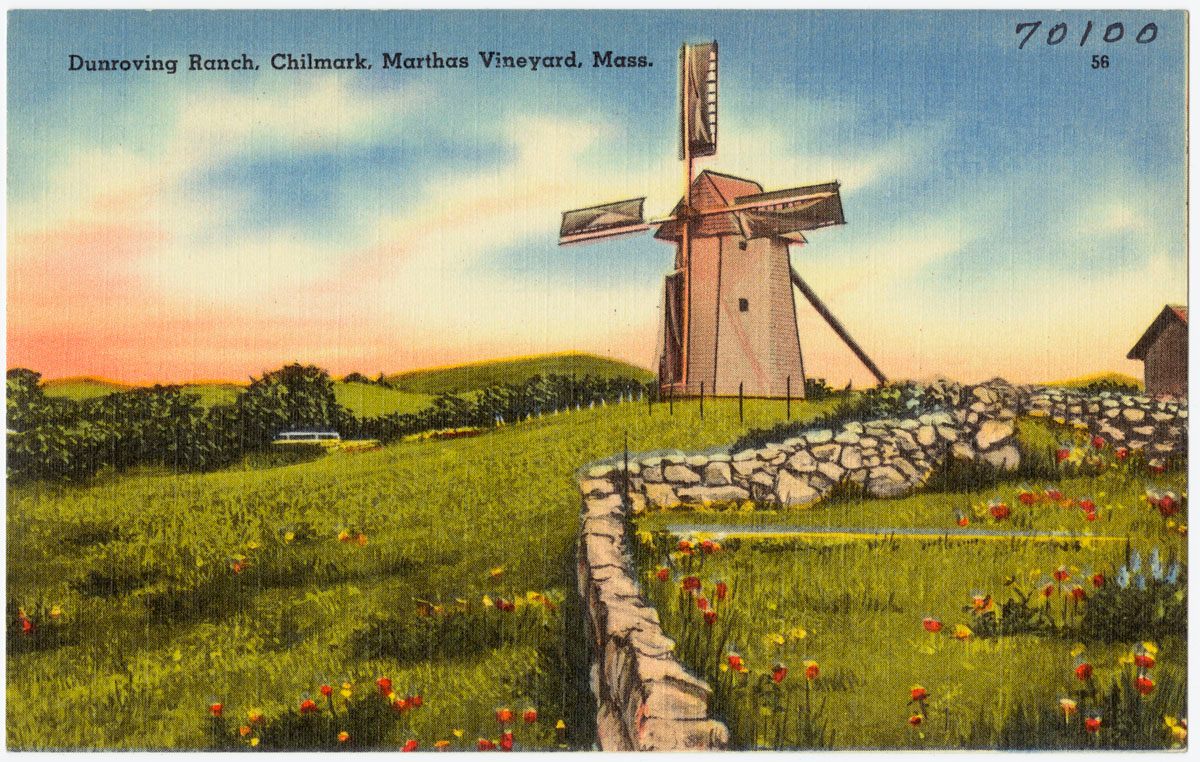

A postcard for Chilmark, at Martha’s Vineyard. (Photo: Boston Public Library/CC BY 2.0)

“It was generations that kept popping up in very isolated communities,” says Poole Nash, who in a lecture points out that more people in the area at that time had been to China on fishing boats than to Edgartown, which was only a few miles away. It was a Deaf utopia: everybody signed to communicate (how else would you speak to your neighbors, parents or friends?)—but hardly anyone outside the community knew about the language. In 1950, the last fluent MVSL speaker passed away. It would take 25 years for the language to reveal itself to off-islanders.

Poole Nash had become interested in sign language during her childhood on Martha’s Vineyard, when she would hide an American Sign Language (ASL) book in her school desk, sneakily teaching herself the alphabet. She learned that her great-grandmother knew signs, and they began “a secret language between us,” says Poole Nash, who began volunteering a camp with Deaf children at age nine, and made friends with Deaf peers near her secondary boarding school. (Usage note for “Deaf” versus “deaf”: Deaf is an identity and culture, while deaf refers to a condition.)

By the time she’d reached her freshman year at Boston University, where she studied American Sign Language, the dominant sign language in the United States, “the head of the department said, ‘Oh my gosh, you sign better than I do,” says Poole Nash. She was quickly sent to a new sign language research group called the New England Sign Language Society, where linguists from colleges like Harvard, Brown and MIT asked new questions about signs. “I just sat there with my jaw open for the whole first meeting,” Poole Nash says. “I had no idea that you could do this kind of research on sign languages–it was just how you did research on Greek or Latin.”

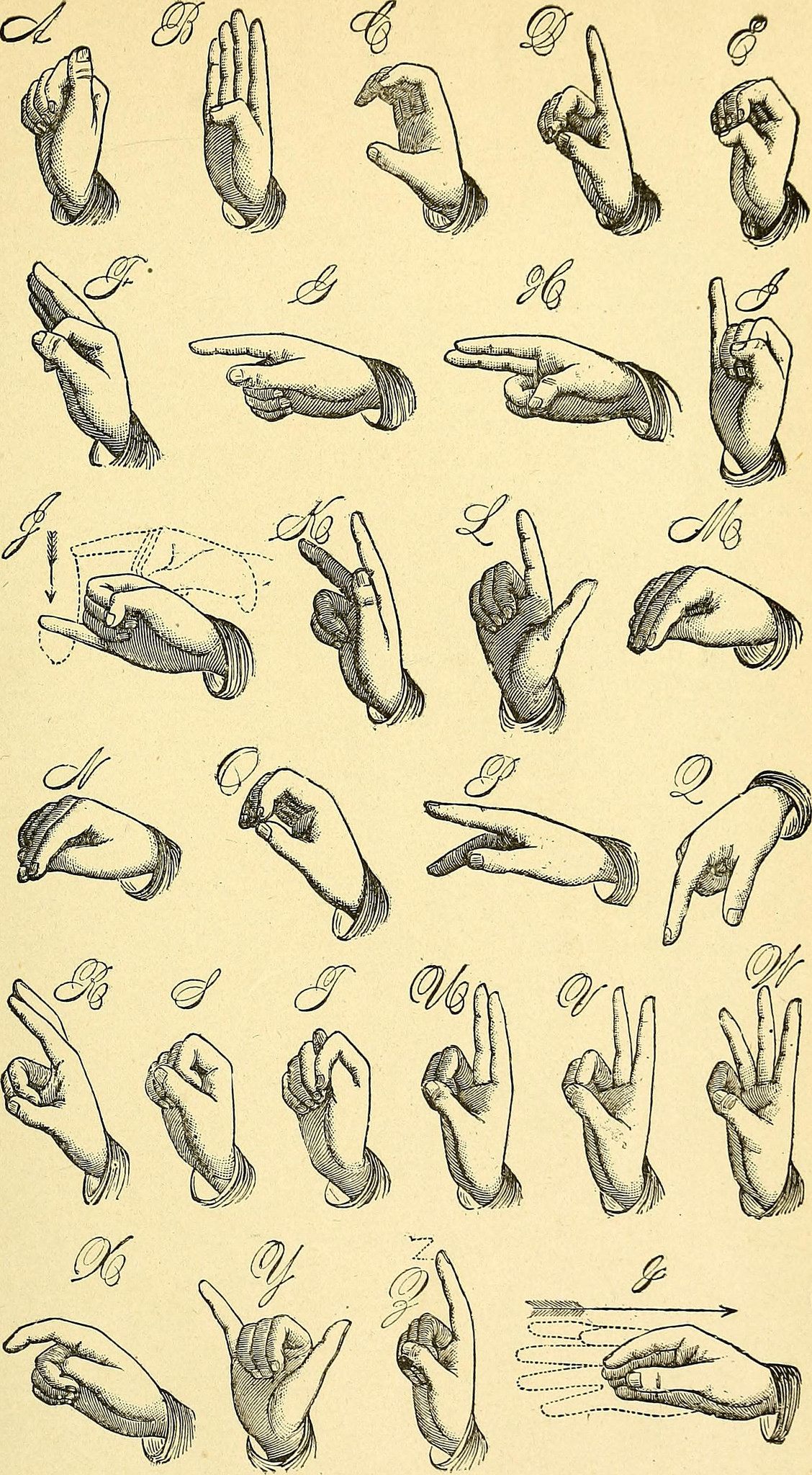

A 19th-century sign language alphabet chart. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

This was in the earliest days of sign language research, just a decade after academics began studying sign languages using a linguistic approach. Prior to this, any characteristic of sign language that differed from standard English was considered a “deaf idiom”, rather than the lingual syntax it is. Poole Nash ordered every sign language book she could find, but while they all made connections between gesture and sign, they didn’t talk about how words originated.

A paper by linguist Nancy Frishberg showed that older signs used two hands while newer signs used one, but no one knew how or why that happened. “A discussion was going on that was ‘how can we find out about old signs, and how do they compare to modern signs?’—and right away it clicked for me,” Poole Nash says.

All this time, Poole Nash had assumed her great-grandmother’s signs might have been related to signs from the Native Nations (which may have influenced MVSL), as Chilmark bordered on a Wampanoag reservation. Poole Nash gave her great-grandmother a call. “I asked ‘How do you know these signs?’ and she said ‘Because all these people were deaf.’” Suddenly, all the stories Poole Nash had heard about the island’s former residents came to life in a new way. Her own family knew this community. They were part of it.

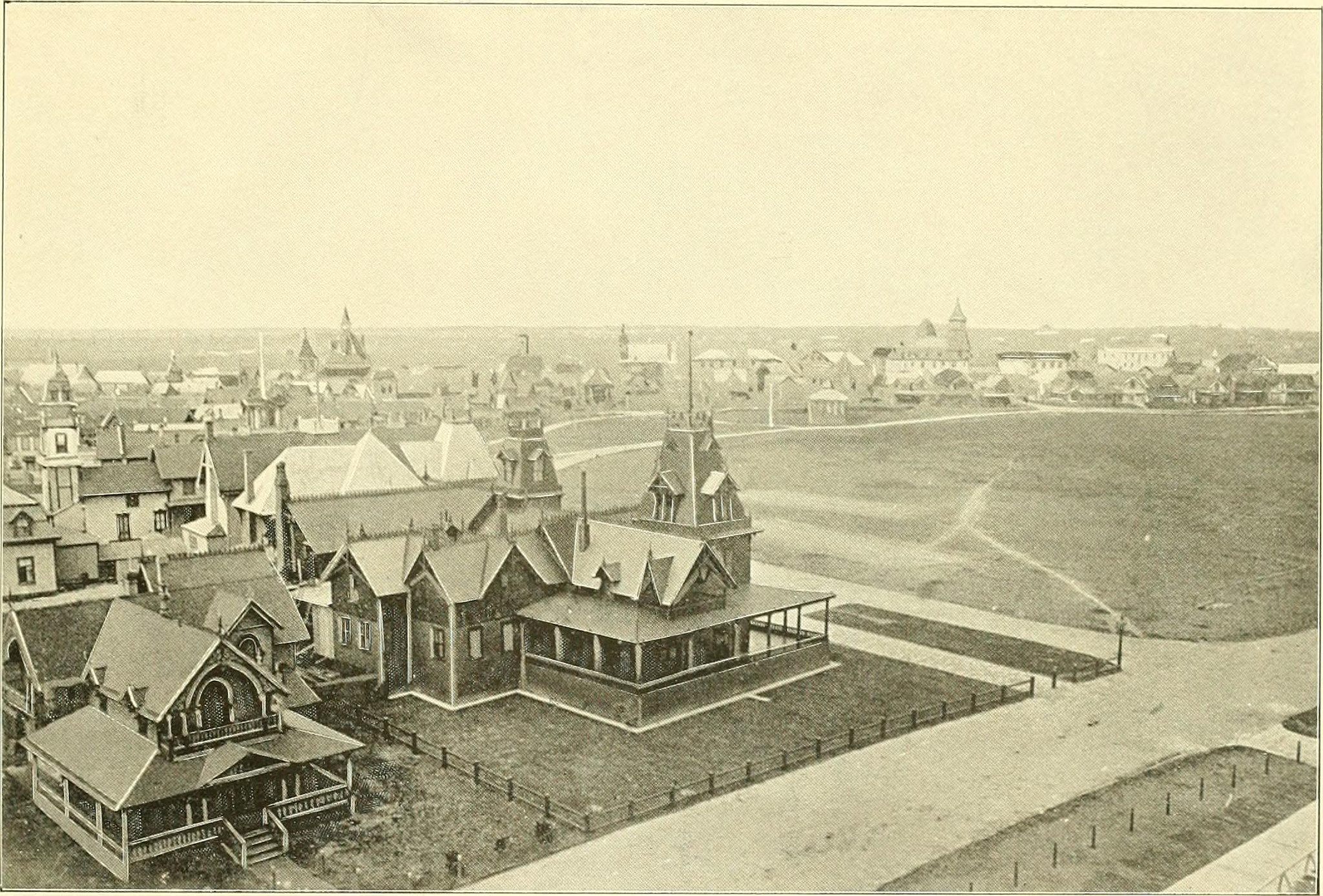

Looking across Martha’s Vineyard, 1897. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

When Poole Nash recounted what she had learned to the linguists at the New England Sign Language Society, the group decided to begin researching the language right away. They packed up an old, hulking camera and headed to Martha’s Vineyard to film the last living island residents who could communicate using MVSL.

Soon, 19-year-old Poole Nash and the prestigious linguists who accompanied her were recording as many words as possible from her great-grandmother, grandfather, and another elderly island resident using their grainy video camera. “It would be much easier if we were doing it today,” laughs Poole Nash. The tape was difficult to study afterward, and the people Poole Nash was interviewing were getting on in years, so it was difficult to make sure the hand shapes she was noting weren’t the result of arthritis.

Also, since her interview subjects weren’t fluent in the language, sometimes their memories were shaky. In a 1970s video of an interview with her grandfather Donald Poole, Poole Nash asks him how to ask someone’s age. He signs “how”, and says “and you point to the person or the child, but how you ask his age, that escapes me.” Abashed, Poole explained: “It wasn’t very necessary to ask that question; in a little town like this, you knew how old people were.”

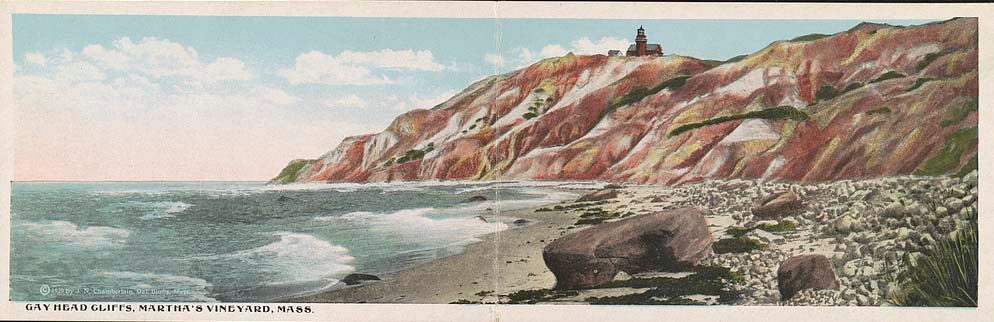

Gay Head Cliffs, Martha’s Vineyard. The town was renamed Aquinnah in 1997. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ds-02431)

In 1994, Poole Nash interviewed another island resident, named Eric Cottle, and added several fish and fishing-related signs to the MVSL list. She found that fishermen there had their own dialect, too. They used a different sign for swordfish that emphasized its fin as seen above water rather than its characteristic mouth, which was how MVSL signers represented it. The word for “codfish” was universally remembered by all.

Sign language has complex linguistic characteristics similar to tones in spoken languages. In addition to words, signs use facial expressions and classifiers: a hand contortion which represents an object or shape rather than an idea. If you were telling a friend how someone bumped into you and made you fall over, instead of signing out every word of the sentence, you’d point your index finger straight up and use that as a “person” to act out the scene, interspersed with your own reaction. When telling a story of any kind, you don’t just use your hands, you use your whole body—using just your hands to have a conversation would be like talking in monotone.

When Poole Nash and others study sign language, they take all of this into account; the differences between various dialects are highlighted to track the language’s history. MVSL-speaking children in the 1800s often attended the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, which was established by Thomas Gallaudet and influenced by French Sign Language speakers. While ASL actually has more in common with French Sign Language than British Sign Language, MVSL might have evolved in the 1600s, when deaf immigrants from Kent, England, arrived to the island; many of the signs from Poole Nash’s great-grandmother resemble British Sign Language, often using two hands instead of one (as ASL does).

American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut. (Photo: David Fulmer/CC BY 2.0)

However, ASL and MVSL might still be related. When Deaf islanders returned home carrying ASL signs with them, it’s possible that they influenced other students at the school. French teacher Laurent Clerc, who taught at the American School of the Deaf in Connecticut, wrote that students learned more sign language from one another than from their teachers. The research that came from the MVSL interviews that Poole Nash initiated also helped further the understanding of ASL, and provided insight into Deaf cultural history, which is rife with past and current discrimination.

With the influx of tourism, better roads and travel technologies, new people were introduced to the gene pool on Martha’s Vineyard. Soon, the island’s unique sign language disappeared altogether. The genetics “burn out very quickly, even in a small community,” Poole Nash says. When the last fluent MVSL resident, Eva West, passed away in 1950, area residents didn’t talk about the lost language when they mourned her.

Indeed, it was lucky for Poole Nash that anyone had been left to speak to her of the island’s hidden Deaf past. “It wasn’t something that you ever talked about because it just wasn’t very significant” to them, says Poole Nash. “When there stopped being any deaf people, they didn’t think about why there weren’t any deaf people; life just went on.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook