The Real Life Tragedy Behind Othello’s Tower

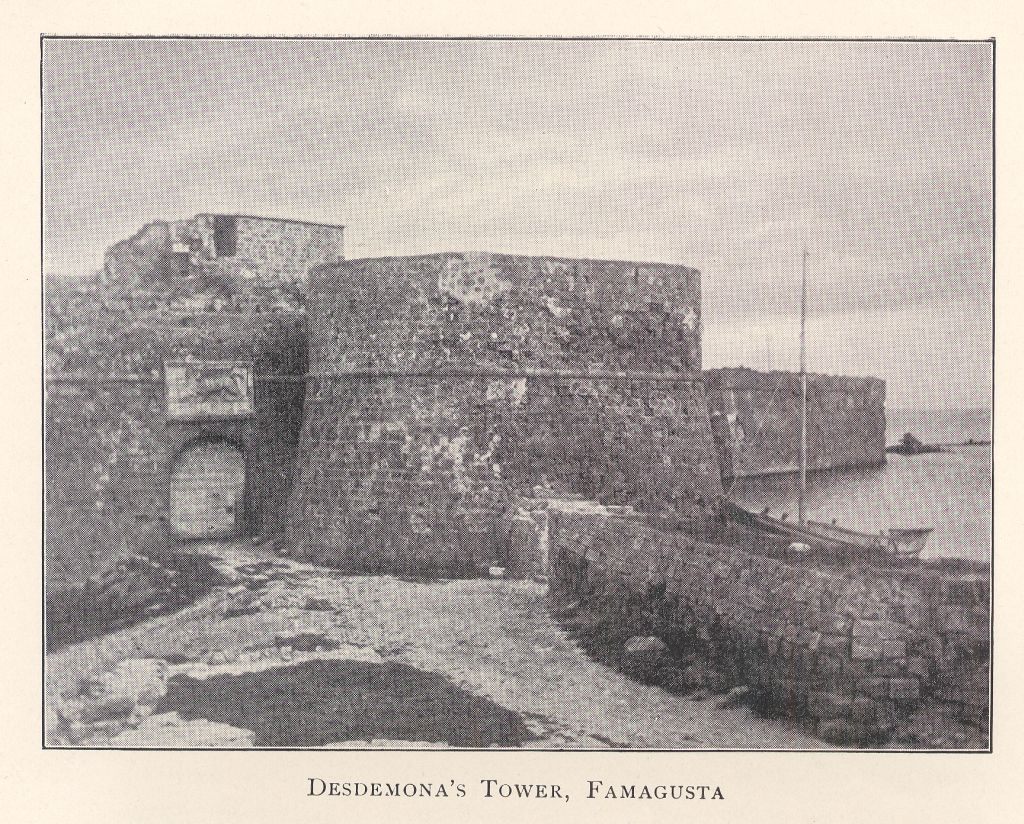

A photograph from the 1900 of the fortress walls and tower in Famagusta. (Photo: Travelers in the Middle East Archive)

A photograph from the 1900 of the fortress walls and tower in Famagusta. (Photo: Travelers in the Middle East Archive)

Unstable stones in the tower had to be removed and reinforced. The 500-year-old Venetian system of channels and cisterns were restored. New roof coverings and underground drains were built to save the castle from water damage.

All for the love of “Othello.”

A seaside citadel believed to be the fictional setting of Shakespeare’s famous tragedy had been in slow decline in northern Cyprus for decades. But after a year-long makeover, the tower reopened to visitors this week, with a performance by actors from both sides of the ethnically divided island.

The opening reception at Othello Tower in Famagusta on Thursday, July 2. (Photo: Courtesy United Nations Development Programme Partnership for the Future)

The Othello Tower sits along the walled port of Famagusta, which was a glitzy tourist magnet until 1974, when a coup backed by the government of Greece was swiftly followed by the Turkish invasion of Cyprus. Since then, the island has remained split in two, with Greek Cypriots living in the south and Turkish Cypriots in the north, separated by a United Nations-patrolled no man’s land known as the Green Line. Famagusta lies in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, an internationally shunned state that was declared in 1982 and is recognized only by Turkey.

The partition has taken its toll on Cyprus’ monuments. But as political reunification talks stalled, some Greek and Turkish Cypriot leaders joined forces in 2008 to form the Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage. Together, they identified about 2,800 culturally significant sites across the island and secured funding from the European Union to perform emergency conservation work on some of the most at-risk churches, mosques, baths and other historic buildings.

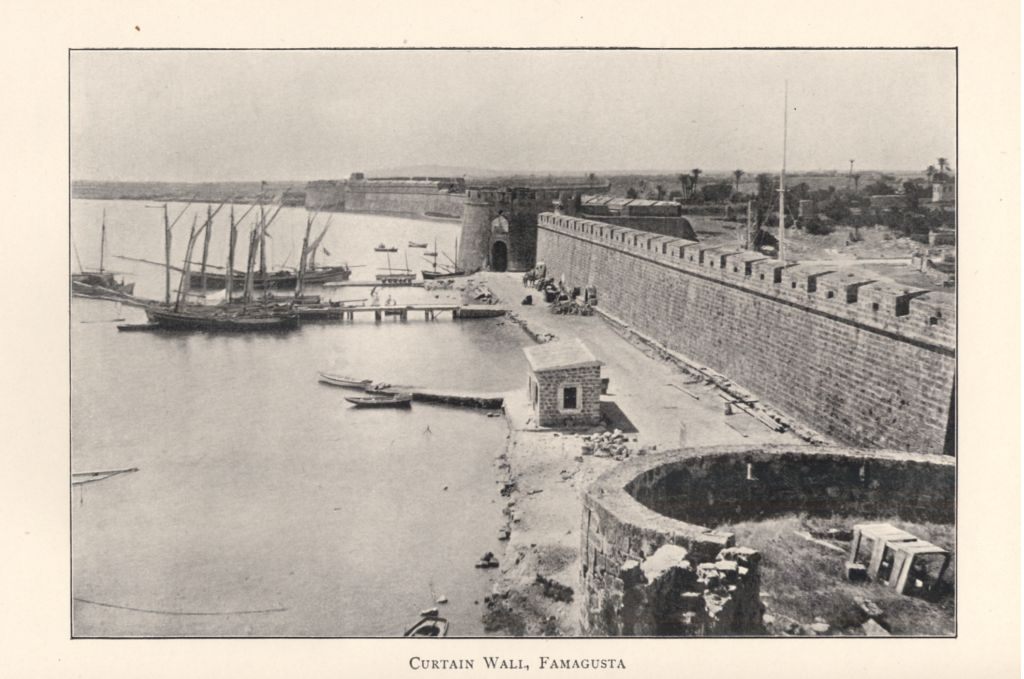

Famagusta in 1900. (Photo: Travelers in the Middle East Archive)

“After we consider that we are losing our monuments, we start to love them,” Takis Hadjidemetriou, the Greek Cypriot representative on the committee, told Atlas Obscura. “When you are going to lose something, you discover how important it is.”

The imposing Othello Tower was first built in the 14th century by the Lusignan Kingdom, and it was strengthened by the Venetians who took control of Cyprus in 1489. The latest renovation, the first since the Cyprus was divided, cost just over 1 million Euros and was completed by a Turkish Cypriot contractor. The renovated walls of the citadel now offer a view of a shipping harbor to the immediate north and, to the south, the abandoned high-rise resorts of Varosha, the beach that attracted the likes of Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton in its heyday but has turned into an off-limits military-monitored ghost town after its mostly Greek Cypriot inhabitants were forced to flee in 1974.

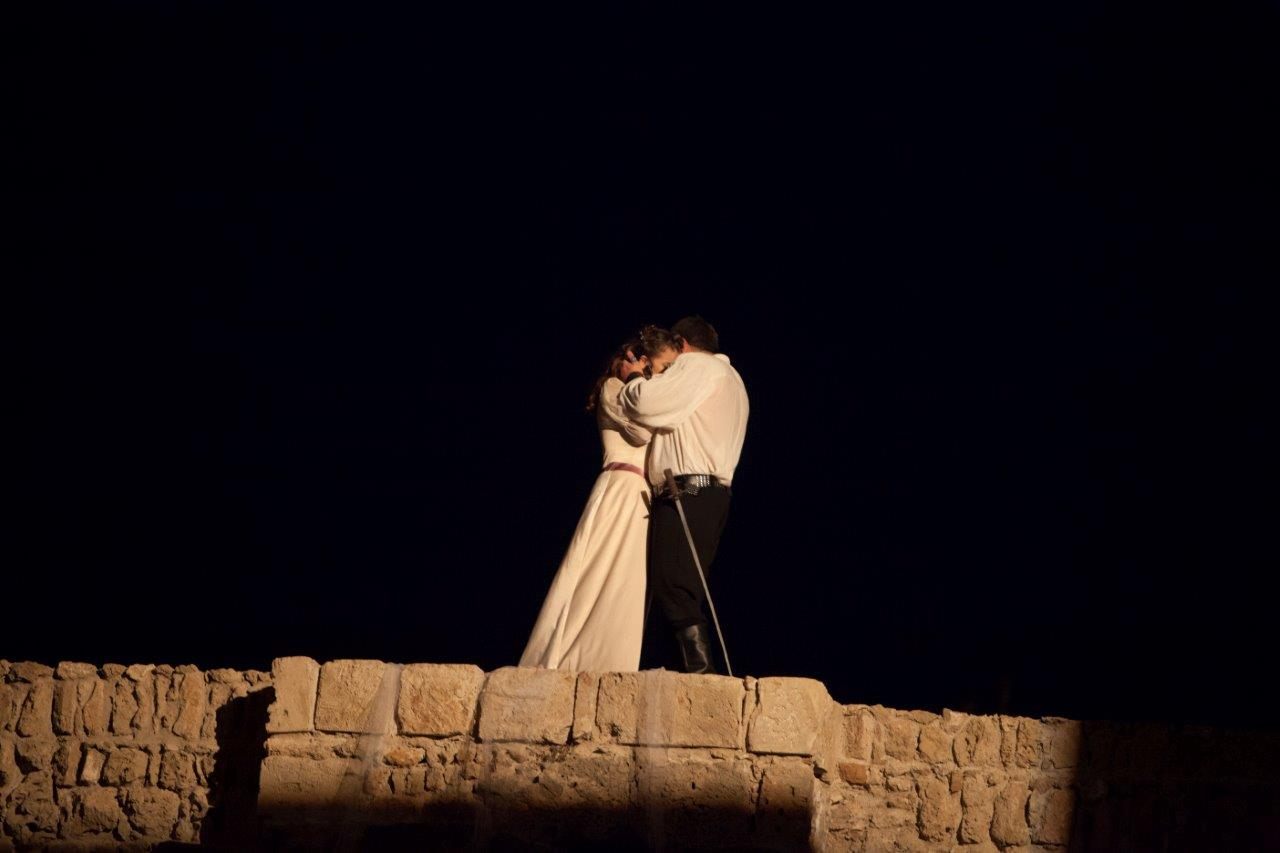

Othello and Desdemona on the wall of the tower. (Photo: Courtesy United Nations Development Programme Partnership for the Future)

The tower underwent a $1 million Euro restoration over the last year. (Photo: Courtesy United Nations Development Programme Partnership for the Future)

“Apart from our hard work, the most important achievement of the committee is the establishment of trust and confidence between its members,” Ali Tuncay, Hadjidemetriou’s Turkish counterpart on the committee, said during a reopening ceremony Thursday night. “They have a common vision for the cultural heritage monuments. For us, they are not just the monuments of Muslims, Christians, Turks, Greeks, Venetians or Lusignans; they are the common heritage of humanity.”

To celebrate this weekend’s reopening of the tower, Greek and Turkish Cypriot actors staged an abridged performance of “Othello,” Shakespeare’s tragedy about a Moorish general who strangles his Venetian bride, Desdemona, after his ensign, Iago, convinces him she’s been unfaithful. It’s not exactly a play about unity, but the themes of power struggle resonated with Hadjidemetriou.

“We had our Iagos who destroyed the country and our lives and brought a lot of misery,” Hadjidemetriou said after the play. “The message was given by tonight’s performance: A brave man so easily swayed by some conspirator with jealousy in his heart can destroy everything. We have to take our lessons from history.”

Cassio and Iago, played by Cypriot actors, in the July 2 performance. (Photo: Courtesy United Nations Development Programme Partnership for the Future)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook