The Scrappy Female Paleontologist Whose Life Inspired a Tongue Twister

Mary Anning, pictured pointing at a fossil on the ground next to her dog, Tray. (Image: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons)

Say “she sells seashells by the seashore” quickly, three times in a row.

Now, try the more historically accurate version: Mary Anning peddles dinosaur parts on the Jurassic Coast as one of the world’s first, unheralded fossil hunters.

Born in 1799, Anning ran a fossil stand on England’s Dorset Beach, also known as Jurassic Coast, and it’s often said that she was the real-life inspiration behind the famous tongue twister. At age 12, she dug up a 200 million year-old marine reptile—the first complete ichthyosaurus skeleton to be acknowledged by the Geological Society in London. Over the following years, Anning continued to discover some of the first dinosaur fossils unearthed in Great Britain, as well as helped to clarify that coprolites, known as bezoar stones at the time, were actually fossilized poop. It was only a matter of time before Anning became what some call “the greatest fossilist the world ever knew.” And did we mention she was struck by lightning as an infant?

Growing up in Lyme Regis, England, on the southern shores of Great Britain, Anning had great access to the sea. Her father, Richard, was a cabinetmaker and avid fossil collector, and he showed Mary and her brother how to wade below the cliffs at low tide to search for fossil specimens. He also taught his kids the fundamentals of fossil collection and identification, skills that became crucial when he died in 1810, leaving his family dependent on charity—and fossil sales—to survive.

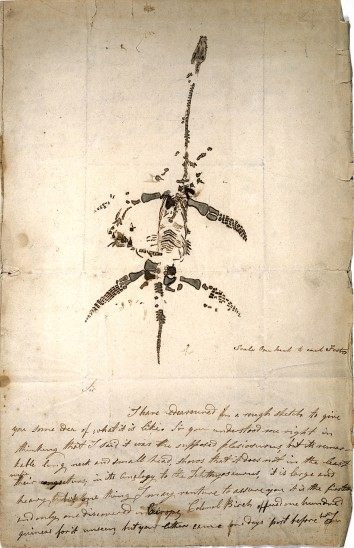

Letter and drawing from Mary Anning in 1823 announcing the discovery of a fossil animal now known as Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus. (Image: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons)

Mary Anning took over the family fossil business in the 1820s. She lacked any formal schooling, let alone a proper MBA, but she could read, write, draw, and reconstruct fossil skeletons. Anning sent sketches of her discoveries to potential buyers: museums and scientists as well as tourists and European nobles, who were constantly seeking out the next great addition to their private collections.

Her brother, Joseph, first stumbled across the four-foot ichthyosaurus skull in 1811, which they initially mistook for a crocodile before noticing its donut-sized eye sockets. A year and a half later, Anning discovered the rest of the body, which was soon purchased and placed in a local museum. However, since museums at the time generally only recognized people who donated rather than sold them fossils, it’s been a challenge for historians to trace discoveries and give credit where credit is due. There may be a whole lot more fossils unearthed by Anning out on display, labeled with the names of others.

In 1817, the Annings came into contact with Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Birch, who offered them support by auctioning off his own fossil collection. Her friend and fellow geologist Henry De la Beche also tried to help out; he painted a prehistoric scene based on her fossil finds and gave her the proceeds from the prints. However, even with outside support and multiple scientific discoveries under her belt, Anning never stopped struggling financially.

Duria Antiquior, a famous watercolor by the geologist Henry de la Beche, imagines prehistoric life on the Jurassic Coast based on Anning’s fossils. (Image: Henry De la Beche/Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons)

In 1823, Anning discovered the plesiosaur, a Mesozoic marine reptile with a long neck, tiny head, and big paddles. Being not only poor but also a woman, Anning was basically a mangy dog on the outskirts of the Oxbridge-educated scientific community. Male geologists would sometimes publish her findings as their own work, and in a letter from the period, one charming fellow writes to another about the new plesiosaur without any mention of Anning whatsoever. Scientists doubted the validity of her finds, and few were willing to take her seriously—that is, until famous French anatomist Georges Cuvier declared her plesiosaur specimen to be genuine.

But first, we need to back up for a second—nothing about this scene is normal. In 1823, Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species (1859) wouldn’t be published for another 36 years, and the term “Darwinism” wouldn’t integrate itself into British vocabulary until the 1860s.

While 10 year-old Anning was busy digging up ancient shells and skulls, Europeans were still convinced that the world was just 6,000 years old. The Bible was their textbook, and the idea of extinction (where were these croc-like creatures with donut-sized eyes now?) was an insult to those who believed that God was flawless. Plus, there was always the argument that these “extinct” creatures had merely relocated to the bottom of the ocean.

A sketch of Anning at work by her friend and colleague Henry. (Image: Henry De la Beche/Public Domain/Wikipedia Commons)

It was Georges Cuvier (1769-1832), who started to get people thinking about extinction. By the 1700s, fossil discoveries were already in the mainstream, but for a long time people believed they belonged to species that had simply migrated elsewhere, not disappeared entirely. But after closely studying a set of elephant fossils, Cuvier declared that an entire species had completely vanished from the planet (which back then was still at the center of the sun’s orbit). Whether these extinctions occurred gradually or were set off by violent events (a theory known as catastrophism), would continue to remain a matter of debate.

So, in pretty much all of 19th century Europe, Anning’s discoveries of ichthyosaurus and plesiosaurs, alongside the first British pterodactylus macronyx and squaloraja fish, were unwelcome, and even insulting. The fact that a poor spinster had dug them up herself on the beach made it even more absurd.

While she sometimes collaborated with male scientists, Anning stayed single her entire life. Bestselling author Tracy Chevalier found this fascinating, and in 2010 came out with Remarkable Creatures, a historical novel co-narrated by Anning and her friend Elizabeth Philpot, a middle-class woman 20 years her elder who became her fossil finder-in-crime. Chevalier shared on NPR that in addition to trying to make fossils sexy, her book tries, in a way, to answer the question, “What do women do who don’t find the Mr. Darcy of the Jane Austen novels?” The answer seems pretty obvious: unbury empirical evidence of extinction.

A Rhomaleosaurus cramptoni skeleton displayed next to a description of Mary Anning. (Photo: Niki Odolphie/Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

A Rhomaleosaurus cramptoni skeleton displayed next to a description of Mary Anning. (Photo: Niki Odolphie/Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

Despite being long overlooked, Anning did receive some positive recognition for her work (or at least for her divine luck). After visiting Anning in 1824, Lady Harriet Silvester, the widow of the former Recorder of the City of London, wrote in her diary:

“It is certainly a wonderful instance of divine favour - that this poor, ignorant girl should be so blessed, for by reading and application she has arrived to that degree of knowledge as to be in the habit of writing and talking with professors and other clever men on the subject, and they all acknowledge that she understands more of the science than anyone else in this kingdom.”

Mary Anning died of breast cancer in her hometown at the age of 47. Her obituary was published in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, an organization that didn’t admit women for another 57 years. Anning remains the pride of Lyme Regis, and people still go looking for their own fossils on Dorset’s Jurassic Coast, now a World Heritage Site. Anning was selected by the female members of the Royal Society as the third most important British woman scientist, beaten only by Dorothy Hodgkin and Rosalind Franklin. The current director of the Lyme Regis museum, which was originally built through a donation by Elizabeth Philpot, says that Anning is “one of those characters whose importance (or at least the recognition of her importance) has grown in recent years.”

The Jurassic Coast at Charmouth, Dorset, where people still go to look around for fossils, as Anning once did. (Photo: Kevin Walsh/Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

So did she sell seashells by the seashore? Indeed she did—invertebrate fossils such as ammonite and belemnite shells, to be specific. But she did a whole lot more than sell seashells, and it’s a shame that Anning is more famous today for her tongue twister cameo than for her probing discoveries in a fledgling field of science. To think that as a 10 year old, she was digging up stuff that would shape the world’s fundamental understanding of time, of history, and of science. At that age, most of us were selling lemonade, not dinosaur bones.

This is part of a series about early female explorers. Previous installments can be found here.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook