The Sordid Voyage of the Venetian Gondola

Venice gondola (1880-90), photographed by Paolo Salviati (via SMU Central University Library)

Venice gondola (1880-90), photographed by Paolo Salviati (via SMU Central University Library)

The Venetian gondola evokes thoughts of sipping a sparkling tipple on a romantic excursion, helmed by a straw-hatted gondolier softly crooning into the night. Long before gondolas became the tourist draw that we know today, the flat-bottomed boat had more to do with critical transportation through shallow muddy canals than with a leisurely pleasure cruise. In the 16th century, the gondola was lavishly detailed and symbolic of the grand city of Venice. At one time, 10,000 gondolas took to the waters of the canals, mostly functioning as transportation for the rich. Wealthy denizens could purchase their own rigs for private use, and flaunt them as if they were the sports cars of the 1500s.

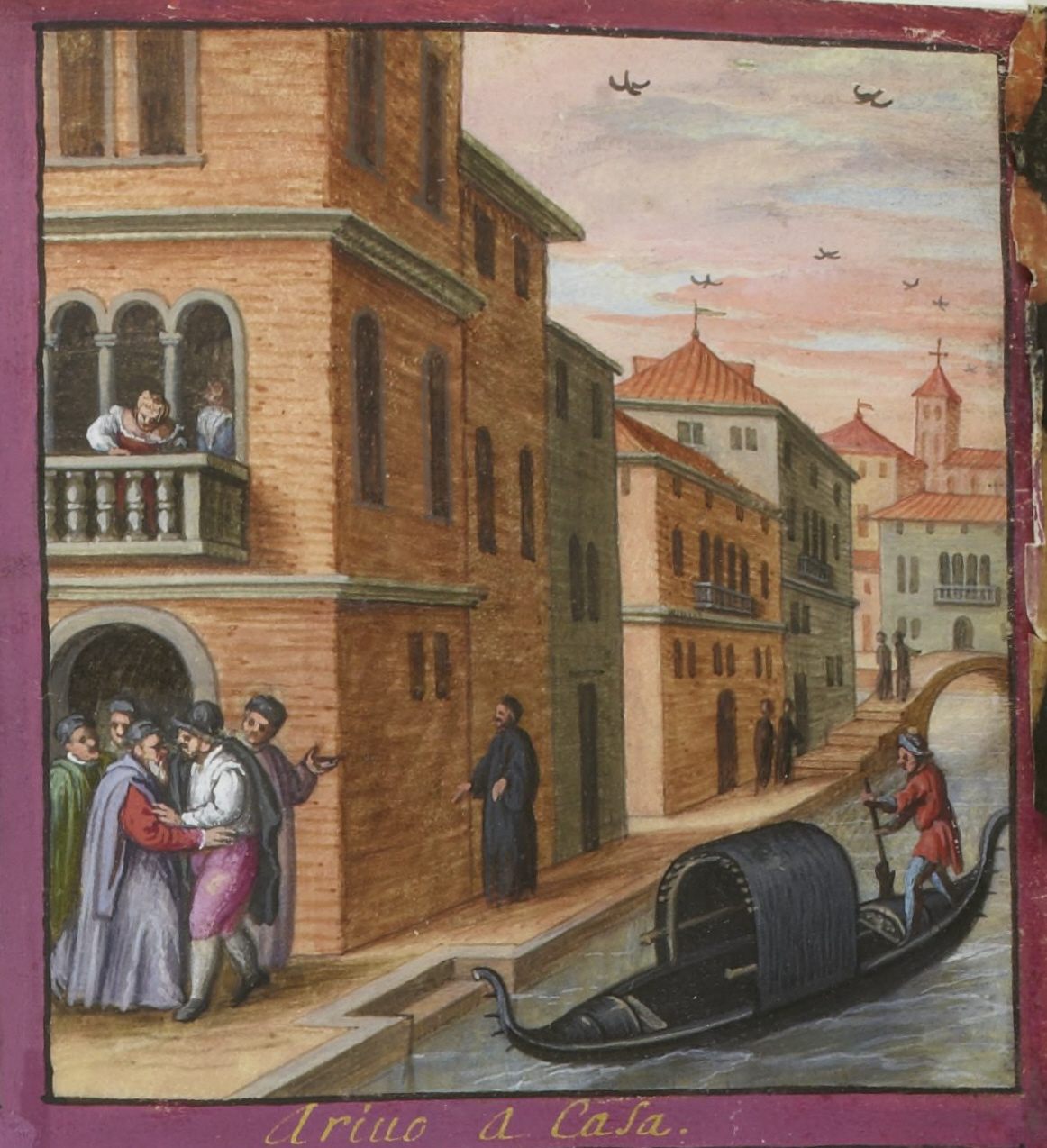

The familiar open gondola fully exposes the passengers, which was problematic for amorous encounters back in its heyday. The most expensive augmentation on the gondola was the felze, a small covered cabin that offered protection, privacy, and a cushy compartment for a good romp. As a popular fixture of intimacy, the felze was a floating thalamus used as a nuptial chamber, granting discretion for newlyweds. The felze also became an inadvertent sanctuary for escaped criminals. These floating love lairs were monumental in perpetuating Venice’s reputation as a libertine city. Eventually the baticopo, or cloth panel that obscured the passengers, was required to be raised at all times so that prostitutes could not sully the pleasure craft with their carnal embraces.

Giacomo Casanova, world renowned Venetian lover and all around bad boy, penned in his memoir, Story of My Life, countless examples of his gondola usage for licentious romances and hasty getaways of the 18th century. He dabbled in gambling, public disputes, and Freemasonry, but mostly he loved the ladies. Obscured by the felze’s shuttered windows, or Venetian blinds, Casanova used the gondola as his own bachelor pad, taking liberties with young lovers under a cloak of darkness.

One of Casanova’s favorite late-night pastimes was to unmoor the gondolas in hopes of enraging the blaspheming gondoliers the next morning. Gondoliers were not always the placid crooners we know today. They were notorious for gambling, fighting, cursing, and extortion.

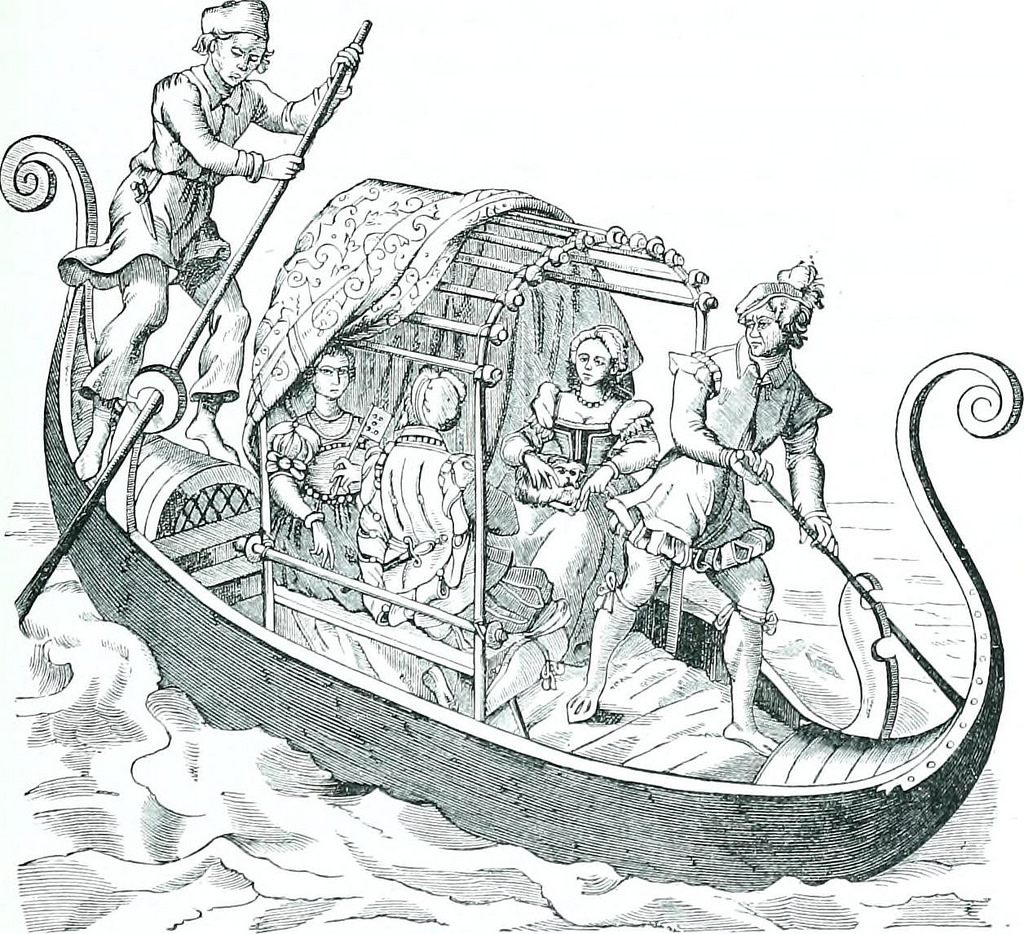

1597 depiction of a gondola (via Internet Archive Book Images)

1597 depiction of a gondola (via Internet Archive Book Images)

1578 illustration of a gondola in Venice (via Bibliothèque nationale de France)

1578 illustration of a gondola in Venice (via Bibliothèque nationale de France)

By the 16th century, the gondola reached the most sumptuous stages of its evolution, boasting exquisite workmanship, materials, and opulent fittings such as brass sea horses, mythical gods, and heads of griffins. The felze contained mirrors, carpets, hand warmers, and upholstery of rich silks, velvets, and brocades. The boats became so overloaded with ornamentation that a sumptuary law of the 16th century forbade all gondolas from bearing extravagant customizations, including fine fabrics, hangings, carvings, and inlay.

Gondola construction adhered to rigorous standards, using exactly 280 components and eight types of wood (cherry, elm, fir, larch, lime, mahogany, oak, and walnut). A specific asymmetrical length balanced the gondolier, who rowed with an oar rather than punting along the water’s bottom. All gondolas were mandatorily solid black, their felze draped in black wool, and all steel adornments were standardized and plain. To enforce a law that banned nobles from flaunting their wealth was indeed one of the government’s great hurdles.

A fleet of all-black, spear-shaped vessels navigating the Grand Canal surely cast a sinister impression. Some believe the black color symbolized mourning of the Venetian Republic, or deaths caused by the Black Plague. More likely the sumptuary law functioned as a mandate against all color, thus the dark vessels retained an ominous air.

Ralph Curtis, “The Bridge of Sighs, Venice,” oil on canvas (via Wikimedia)

Ralph Curtis, “The Bridge of Sighs, Venice,” oil on canvas (via Wikimedia)

In the 19th century, Lord Byron preferred to swim while in Venice, or rather skinny-dip with his courtesans despite the polluted waters of the Grand Canal. Byron was more likely to use a gondola as an escape vessel or even as a “dog house” in which to catch a peaceful night’s sleep after disputing with his wife. In his poem “Beppo,” Byron identifies the foreboding gondola for its ability to hide the truth:

‘Tis a long cover’d boat that’s common here,

Carved at the prow, built lightly, but compactly;

Row’d by two rowers, each call’d ‘Gondolier,’

It glides along the water looking blackly,

Just like a coffin clapt in a canoe,

Where none can make out what you say or do.

Lyric poet Percy Bysshe Shelley described the gondola as “funeral bark” in which he and Byron glided through Venice. He likened the gondolas to “moths of which a coffin might have been the chrysalis.”

Today, approximately 400 gondolas remain in service. However, the modern day gondola experience serves less as a lovers’ clandestine hideaway and more as a languid sail across tourist-flocked waters. And further afield the tradition has spread, including Gondola Servizio at Lake Merritt, Oakland, offering the optional felze-covered gondola ride for contemporary access to the intriguing historic custom, complete with authentically and rigorously trained gondoliers who just may serenade you, oh-so-creepily out of tune.

Gondolas in Venice in 2010 (photograph by llee_wu/Flickr)

Gondolas in Venice in 2010 (photograph by llee_wu/Flickr)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook