The Strange Tale of JFK’s Goat-Out-the-Vote Campaign

One of JFK’s first campaign strategies involved a rambunctious goat.

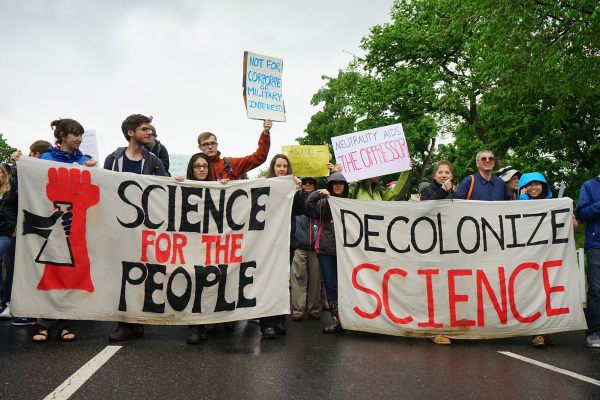

The man, and goat, in question, along with campaign aid Sylvester Colbert and Grand Knight Warren McCully. (Image: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum/Public Domain)

As this turbulent election season marches on, it’s easy to forget that, throughout the history of world politics, a small but steady role has been played by goats.

During June’s European Union referendum, something called gifgoat.party convinced nearly 10,000 people to register to vote by showing them videos of frolicking kids. One of Donald Trump’s personal tax-cutting strategies includes pasturing goats on two of his New Jersey golf courses, making them, legally, large (and strangely barren) farms. And then there’s President George W. Bush’s favorite emergency reading material, The Pet Goat. If three’s a trend, we’re already there.

Less apparent is the potential originator of this campaign staple—none other than President John F. Kennedy, who, during his very first political race in 1946, walked a billy goat around Boston and stole the city’s heart.

It’s tough to imagine such a storied personage walking a goat. But before he was a Democratic wunderkind, JFK was just Jack Kennedy, a young man trying to figure out what to do with his life. Both of Kennedy’s grandfathers had been politicians—his dad’s dad, P.J. Kennedy, served many years as a Massachusetts congressman and senator, and his mom’s dad, John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, was a two-term mayor of Boston. His father, Joseph, was a successful businessman with a web of political ties. He had been grooming his oldest son, Joe, to take up the family game, while Jack traveled, tried his hand at journalism, and finished up an eventful stint in the Navy.

A young JFK in the South Pacific. (Photo: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum/Public Domain)

But in 1944, Joe was killed in action in World War II, blown up in an Air Force plane over the Blyth Estuary. Suddenly, the Kennedy political mantle was up for grabs. Joseph was determined to place it on Jack’s shoulders. “He demanded it,” Kennedy later told a reporter. “It was like being drafted.”

And so in 1946, at age 29, Jack put away his pen and began his first political campaign. If this new career felt like a war, its front lines were Massachusetts’s 11th Congressional District, a swath of Boston that encompassed much of West Roxbury and Charlestown, as well as pieces of Cambridge and Somerville. The district was having a special election to replace Congressman James Michael Curley, who had just been elected Mayor of Boston. The Democratic primary, scheduled for June 18th, was the real contest—the district was staunchly partisan, and whatever donkey made it to the general was a shoo-in for the Washington seat.

Kennedy’s main opponents were formidable: John F. “Spring” Cotter, a Charlestown local, and Michael Neville, a city councilman from Cambridge. Both had experience, and strong community ties. Kennedy didn’t. “He was virtually a stranger to Boston,” writes historian J. Anthony Lukas in Common Ground. Worse, his chief assets—his name recognition and his dad’s money—counted as demerits in the largely working-class areas where he was campaigning. “[Kennedy] is registered at the Hotel Bellevue in Boston, and I daresay he has never slept there,” one opponent accused. A local newspaper renamed him “Jack ‘Jawn’ Kennedy,” calling him “ever so British.”

Massachusetts’s former 11th Congressional District, a tough nut to crack. (Image: Boston Public Library/Public Domain)

“His patrician gloss, the elegant ease acquired at Choate and Harvard and cultivated in London and Palm Beach, was not calculated to go down well in the waterfront saloons of Charlestown, the clammy tenements of the North End, or the bleak three-deckers of East Boston, Brighton, Somerville and Cambridge,” writes Lukas. The political establishment ignored him, too. “He was rich, he was young,” one of his staffers, William J. “Billy” Sutton, later recalled. “They figured he wouldn’t catch on.”

But Jack was determined to try anyway. He set up a number of offices, hired enthusiastic young people to get the word out, and hit the streets. “It was pretty much a blitz campaign,” Sutton said. “One day he made thirty-four speeches, including a trip to the Navy Yard and the Revere Sugary… for a fellow who was supposed to be injured during the war, he really wore me out.” He’d talk to commuters on the street, mailmen in the post offices, firemen in the firehouses, and wait staff in the restaurants where he ate lunch. As Sutton summed up, “It was a meet-the-people program… anywhere people would gather, you’d see Mr. Kennedy.”

One popular gathering place was the local Knights of Columbus chapter, the Bunker Hill Council. Smack in the middle of Charlestown, pretty much every Irish Catholic in town was either a Bunker Hill Knight or related to one (the organization was, and is, literally an old boy’s club, inducting only men over 18). Kennedy’s advisors counseled him to join up, and quick, and so Kennedy put himself forward for the annual induction ceremony.

The Bunker Hill Monument, rising about Charlestown. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-det-4a17971)

The induction parade was, fittingly, on St. Patrick’s Day. As Lukas tells it, the 50 or so candidates seeking inclusion were told to march a prescribed route to the Knight’s Hall, each carrying a symbolic “relic,” like a key or a cross. Kennedy, though, didn’t get off so easy. “Jack was assigned a special burden,” Lukas writes, “a live, frisky billy goat which the future President hauled on a leash past hundreds of amused spectators.” While other relics symbolized certain of the group’s core attributes—authority, mercy—the goat stood for something different: humility.”

The candidate might think he was leading it,” Lukas explains, “but as would eventually become clear, the goat was leading him.”

The young candidate spent a couple of hours getting goat-yanked three miles around the streets of Charlestown. The only known photo from the event, above, shows him gamely holding the bearded animal by the tether, flanked by campaign staffer Sylvester Colbert and Grand Knight Warren McCully, and with a few new giggling fans in the background. That and a secret oath, and he was an official Knight of Columbus.

The Bunker Hill Knights of Columbus visiting the White House in 1961. (Photo: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum/Public Domain)

Maybe it was the goat, or maybe it was the hours spent hitting the pavement, or maybe it was the charisma and talent that would power him through increasingly high-stakes contests, but Kennedy won the primary by a landslide, doubling Neville’s vote total and more than tripling Cotter’s. “Almost overnight,” writes Lukas, “Jack Kennedy had become an honorary Townie.” He proceeded to beat his Republican opponent in the general election, and, eventually, everyone else he ever ran against, bringing him from Congress into the Senate and eventually into the Presidency.

Kennedy never forgot his goaty roots. In 1961, when he was snug in the White House, he invited the Knights of the Bunker Hill Council and their families to a lawn party, inviting them to parade around his new place, huge and elegant and distinctly livestock-free.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook