To Earn His Crown, Germany’s Tofu King Had to Overcome Sausage and the Slammer

The country once arrested purveyors of meat alternatives.

One evening in 1983, a pair of local police officers in the German city of Siegburg stopped by an old butcher shop to investigate reports of suspicious activity. Inside, they found three slightly scruffy twentysomethings with kilos of contraband. Bernd Drosihn, the ringleader, tried to object, but the officers confiscated the offending substances. After a stern reprimand, they handed over a letter announcing a preliminary investigation into the crime: making “Torfu.”

“Every week, we received a new prohibition order from every possible part of the country. The bureaucrats kept at it. Tofu made them completely crazy,” writes Drosihn in his book Tofu: From Bizarre Struggle to an Unassuming Food Source for the World. So crazy, in fact, that subsequent letters included warnings about Tuffo, Tofo, Tortuffo and Tartuffo. “They were so confused and panicked in their fear of any kind of change that they couldn’t manage to arrange four letters in order.”

Tofu had been a staple in China for nearly 2,000 years before Drosihn attempted to make it, but it was still largely unknown in Germany in the 1980s. At the time, both soy milk and nigari, a coagulant commonly used to make tofu, were illegal. As the largest milk producer in the European Union, Germany has a long history of protecting its dairy industry from both international competition and any ersatz products that might cut into sales. To this day, the legal battle continues over whether dairy substitutes made with soy or oat can be called “milk” at all. Until a court battle in 1989, around the time of the fall of the Berlin Wall, the dairy lobby managed to keep soy milk and derivatives such as tofu strictly verboten. Worse, to the average West German citizen of the time, tofu was a foreign oddity largely associated with anti-establishment types.

“Soy products were totally unknown back then,” Drosihn says. “After the free-spirited mentality of the late 1960s, all those stuffy German bourgeoisie values came back with a vengeance in the 1980s. Vegetarian products made by young hippies like us were quickly banned.”

One glance at Drosihn and his fellow conspirators would have confirmed the police officer’s worst fears. Shaggy-haired and with a penchant for rule-breaking, the tofu-makers fit the hippy stereotype perfectly. As Drosihn told the German television program Galileo years later: “legal, illegal, didn’t fucking matter—that’s how it was back then.” The complaints were so regular that members of the self-declared tofu collective dubbed their bureaucratic antagonists the Fleischbeamte, or meat police. At one point, local authorities threw Drosihn and one of his cohorts in prison.

“Honestly, I only spent a night in custody,” says Drosihn, now 61. “It wasn’t all that bad.”

If Drosihn sounds smug when he recounts the story these days, it’s with reason. As the head of TofuTown, the single largest tofu producer in the European Union, he loves to tell the tale of his clandestine beginnings. Today, he presides over a soy empire that generates more than €60 million in annual revenue. His three factories transform more than 30 million metric tonnes of soybeans into more than 100 products annually, including vegan currywurst, faux-chicken nuggets, and soy steaks. His company headquarters are located in the city of Wiesbaum on Tofustraße, literally “Tofu Street.” His success is so unrivaled that more than one German media outlet has dubbed him the “Tofu King.”

Despite his considerable wealth, Drosihn eschews Porsches and other trappings of capitalist success. He’s ditched the more flamboyant prints of the ‘70s and ‘80s, but still prefers a beanie to a suit. While the Tofu King celebrates his product’s widespread success, he’s proud of the fact that he was drawn to a plant-based diet long before it was trendy or even socially acceptable.

“When I was about 10 or 12 years old, I watched my aunt slaughter and gut a poor, old chicken. I saw another relative kill a rabbit. Ever since then, I’ve refused to eat meat,” Drosihn says. “At the time, the idea of being vegetarian was a completely alien concept. Children were supposed to eat whatever was on the table. So instead of swallowing, I would store meat in my cheeks, then spit it out in the flower beds or on the street.”

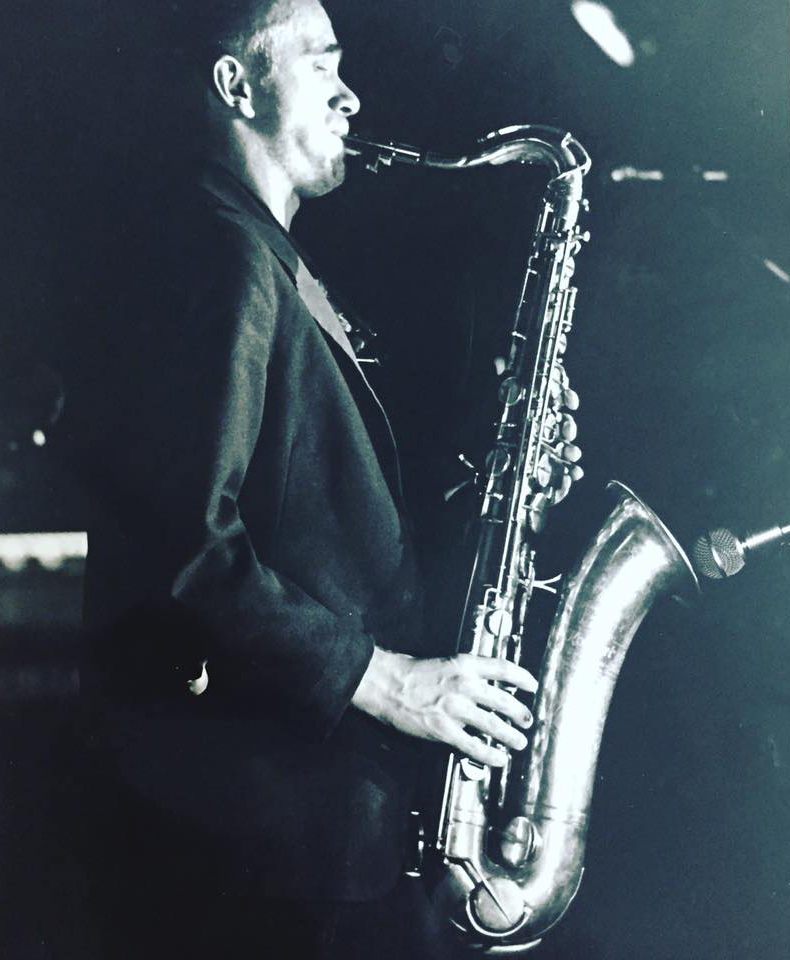

Drosihn’s brand of subversive vegetarianism may have started at a German dinner table, but it crystallized into a full-fledged philosophy during a short stint in New York City. While in his early twenties, he picked up a modest gig as a saxophonist in a band.

“Every night, we played in a dive called Soul Bar across the Hudson in Jersey City. The club looked a little bit reminiscent of Bada Bing! in The Sopranos,” Drosihn says. “Personally, it was a life-changing time for me in which many doors opened. A little piece of New York has always stayed with me.”

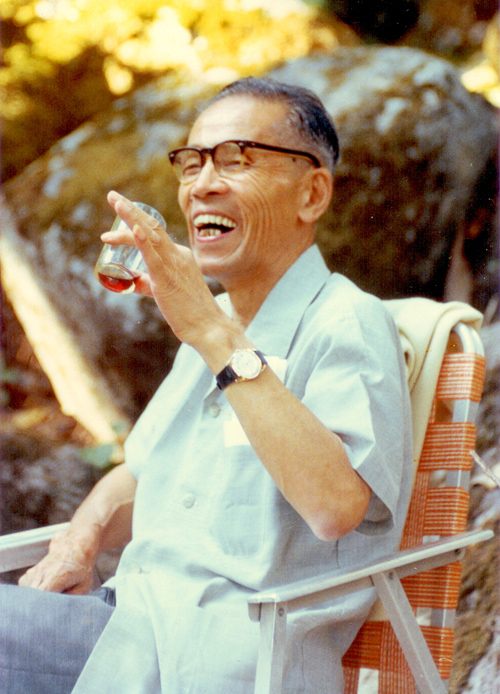

In between gigs, he met a waitress who worked at a macrobiotic restaurant in Greenwich Village. Founded in the 1950s by Nyoichi Sakurazawa, better known as George Ohsawa, macrobiotics loosely drew on certain elements of Zen Buddhism and helped spread vegetarianism throughout the United States. The young musician was smitten with both the woman and the countercultural lifestyle she so effortlessly embodied. She introduced him to tofu, which was cheap enough to fit a saxophonist’s budget, and before long he was hooked.

As in Germany, the initial hype surrounding tofu in the United States had a great deal to do with purported health benefits and a refutation of societal norms. Benjamin Franklin wrote about it in 1770, but tofu wouldn’t properly arrive in the United States until the early 1900s, when Yamei Kin, a Chinese-born doctor, touted it as a meat alternative.

The United States has a long, complicated history of assimilating staple foods from diaspora cultures, while in Germany, the phenomenon is still fairly new. By the time Drosihn showed up, tofu would have been a familiar enough foodstuff to many Americans, a staple of the Moosewood Cookbook-owning set, yet few Germans had ever heard of it. This, despite the fact that the Austrian botanist Friedrich Haberlandt promoted soybeans as a crop in the 1870s. The nutritious legumes thrived in German soil, yet never really took off commercially.

“Germany, until very recently, was not considered an immigration country. That doesn’t mean that there weren’t new people coming in, especially in urban areas like Berlin,” says Ursula Heinzelmann, a Berlin-based food historian. “The difference is in the country’s cultural perception of itself. That’s how, perhaps in the U.S., new foodstuffs are adopted more easily, whereas [in Germany], it’s much more compartmentalized.”

Part of the reason that “German consumers… never fully embraced soy and its derivatives,” as Heinzelmann writes in Beyond Bratwurst: A History of Food in Germany, stemmed from the fact that, in the early 1900s, cheap, imported soybeans were typically used as either food for livestock or as substitutes for pricier meat products. Soybean oil and margarine were inferior substitutes for butter, while Maggi, which began manufacturing bouillon cubes and sauces in Germany in 1897, could be used to stretch a weak stock with a hit of artificial umami. A darker negative association may stem from the fact that the Third Reich promoted a fanatically healthy diet rich in wholegrain and soy. A Hitler Youth pamphlet even referred to soybeans as “Nazibohnen” (“Nazi Beans”).

For the generation that had endured rationing under two World Wars, meat was a symbol of prosperity. As soon as the economy began to recover, survivors were eager to put the memories of scarcity behind them. It wouldn’t be until decades later that the consumption of schnitzel and pork knuckles would become a question of morality rather than means.

Upon returning to Germany, Drosihn and his fellow tofu evangelists founded Kollektiv Soyastern. Their quest was more ideological than financial, more act of defiance than business plan. They had plenty of passion, but one small problem: None of them had the faintest idea how to make tofu.

“It was very much a trial-and-error, do-it-yourself kind of process,” Drosihn says. “It took a long time before we were able to put together a solid block of tofu in that back room in the health food store.”

According to Drosihn, it would take the better part of a year before the collective produced anything resembling the desired blocks of wobbly protein. Their initial setup was on the low-tech side, meaning that every step, from stirring vats of soy milk to pressing the blocks with stone, needed to be done by hand. The members of Kollektiv Soyastern likely would have given up and sought more fruitful employment had Drosihn not sunk all of his savings into the project.

By 1982, the collective was selling tofu out of a car. Before long, they found a more permanent setup: a former butcher shop in Siegburg. Before setting up shop, they performed a quasi-Buddhist purification ritual with incense sticks and candles to rid the place of animal spirits.

When the police knocked on their door the following year, Kollectiv Soyastern was in too deep to back down. If anything, the authorities’s response seemed to egg the vegetarians on. Drosihn gleefully recalls smuggling tofu into the local jail.

Kollektiv Soyastern’s biggest problem wasn’t bureaucrats, however, but a population uninterested in their product. In 1989, they were running out of money to pay their bills. When they went to a court for help, the judge took one look at their sample and laughed, “Tofu! Any idiot can see why you’re broke.” They might have gone under had they not learned about smoked tofu. With its firm texture and more meat-like flavor profile, “Soyastern-Räuchertofu” quickly became “the blockbuster of the tofu universe,” writes Drosihn. Before long, the crew was schlepping tofu, smoked tofu, and tofu burgers around in a beat-up Suzuki van labeled with the sign “Tofu kommt!” (“Tofu is coming!”)

Nowadays, the number of German vegetarians and vegans ranks in the millions. Tofu’s growing success in the country represents a larger confluence of factors, including a growing concern about the climate crisis and a rise in wellness trends. It also reflects how urbanites in Germany’s increasingly cosmopolitan cities see themselves. While Drosihn may have introduced Germans to soy in culturally familiar forms like veggie-sausages and burgers, today some of the most popular places in Berlin to eat tofu are Liu 成都味道面馆 Nudelhaus and Chungking Noodles, both of which serve hand-made Sichuan-style noodles. In the tony neighborhood of Mitte, locals spend upwards of €65 for weekly tofu-making workshops using organic Bavarian-grown soybeans at a “soy concept store” founded by two expats from Tianjin, China.

The police, the judges, and everyone else may have ridiculed a bunch of upstart kids making “torfu,” but Drosihn got the last laugh. His 40-year crusade to bring tofu to the masses made him a fortune and left an indelible mark on the eating habits of a nation.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook