The Dangers of Train Yards, Through the Eyes of Railroad Employees

A collection of photos from the 1960s tried to show why locomotives need two people in the cab.

In 1960, looking west from the Texas and Pacific freight yard in El Paso, Texas, you’d see the lines of the rails curving off to the north, towards the city buildings and smokestacks in the distance. In the yard, after an engine gave a rail car a push on its way, workers might uncouple the car and let it roll under its own momentum down the way, or simply release a brake to start it in motion. During the day and the night, children from the neighboring houses would find their way into the yard, along with itinerant workers and drifters. Cars and trucks following Tornillo Street, a public road, across the dozen or so rails in the yard, might find heavy train cars traveling straight towards them or blocking their way.

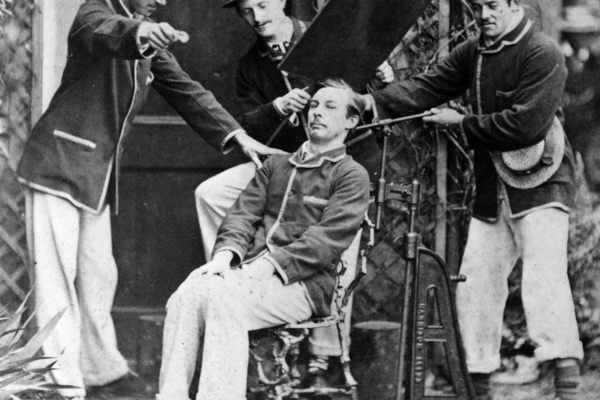

For the men working on the trains, it felt like a dangerous situation. The photos shown here were taken by engineers and other rail workers on tracks across the country, in an effort to prove how hazardous these places could be and to show why cutting crews was a terrible idea.

Starting around the 1950s, the railroad business had started sliding into a decline, even as the engines had modernized from wood- and coal-burning to sleeker diesel machines. But both passenger and commercial business had fallen as cars and trucks became the dominant mode of transportation in the United States. Under President Eisenhower, the Interstate Highway System was authorized in 1956. Railroads saw the future and were trying to cut costs—which meant cutting crews—where they could.

Since the 1920s, safety regulations had helped determine the make-up of crews on the train. In the days of steam engines, every train had an engineer, who operated the train, and a fireman who’d keep the boiler running. By the 1950s, the fireman’s job had changed: The new engines didn’t need someone shoveling coal in. The industry wanted to start cutting these jobs, but the rail workers and their unions fought back. Without two people in the cab of the locomotive, they argued, the engineer and the rest of the train would be in danger.

For years, starting around 1956, the railroads and their workers fought over “crew consist” rules—how many people would make up a train crew. Finally, in 1960, when neither side could settle on new rules, they agreed to call for a federal commission to weigh in. In preparation for the commission, the union had more than 30 railroad employees take photos of their workplace in an effort to demonstrate the hazards firemen could help navigate around.

Thanks to a new effort at Cornell University’s Kheel Center, an archive focused on the history of labor relations, those photos—more than 1,655 in all—are now available digitally. To the untrained eye, they display a striking uniformity. Railroads would use the same architects and the same designs on their facilities across the country. When different rail lines interconnected, they’d also have standardized exchanges. A rail yard in Seattle might not look different from a rail yard in Texas or one in Boston.

But that’s not what the men taking these pictures saw. Each train yard had its own unique hazards and challenges. “A lot of them are showing curves in tracks,” explains Liz Parker, an archivist at the Kheel Center. “Depending on what direction a diesel engine is moving, you can only really see to one side of the cab and directly in front of you. The minute you start to turn, you can’t even see the tracks in front of you, let alone debris, people, or trucks.” Many of the photos show blocked lines of sight, along with foot and car traffic on the train tracks, in an attempt to show why a crew would benefit from having someone on either side of the cab sticking their head out to see where the train was headed.

Ultimately the photos didn’t do the trick. Diesel engines could be designed differently than older units, without a long boiler at the front of the train. “With the new technology, the crew cab could be placed right at the front of the unit, yielding dramatically improved visibility and nullifying some of the pro-fireman argument,” says Robert Lettenberger, Education Director at the National Railroad Museum.

The unions had other arguments—radio communication wasn’t reliable, and the fireman could help communicate with a brakeman when technology failed, for instance—but the railroads’ need to cut cost and the push for modern efficiency won out. Today, these photos represent a lost world, perhaps the last moment when railroads were still some of the most important companies in America.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook