The Elusive, Maddening Mystery of the Bell Witch

A classic ghost story has something to say about America—200 years ago, 100 years ago, and today.

Sometimes we don’t pay close enough attention to the stories we’re given. That, at least, is the message of many a ghost story. Take the horror film The Blair Witch Project, the 1999 cult blockbuster by Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez that purports to tell the true story of three filmmakers who disappeared while working on a documentary about the legend of the Blair Witch, a ghost that haunts the forests near Burkittsville, Maryland. The young people—actors, all, though it didn’t seem that way at first—discount their interviews with locals (“Do you remember something that Mary Brown said the other day?” one of them asks her companions, before muttering to herself, “Fuck, I wasn’t listening to her because I thought she was a lunatic.”), only to find themselves the witch’s next victims. It is, of course, a common trope in ghost tales and horror films: We know the outlines of the story, we tell it to spook our friends, but we haven’t really listened. The mistake only becomes apparent once it’s too late. This is true both for the characters within a story and for us, the audience of readers or viewers. Ghostly narratives carry lessons for us, too, even if we’re not in imminent danger.

According to Ben Rock, The Blair Witch Project’s production designer and the person responsible for the film’s mythology, the Blair Witch was inspired by (among other stories) an actual legend: the Bell Witch of Tennessee.* In addition to Myrick and Sánchez’s film (and its two sequels), there’s also 2005’s An American Haunting and several direct-to-video offerings, along with an A&E series, Cursed: The Bell Witch. The legend has inspired all manner of music, from Charles Faulkner Bryant’s classical cantata to the Seattle-based doom metal band that took Bell Witch as its name. There is also the tourist trap in Adams, Tennessee, about an hour north of Nashville: the Bell Witch Cave, which remains enduringly popular despite having only the most tenable connection to the legend itself. In a dozen ways, it’s a story we’ve been telling over and over again, as if we know it, without really paying attention to what it’s trying to tell us.

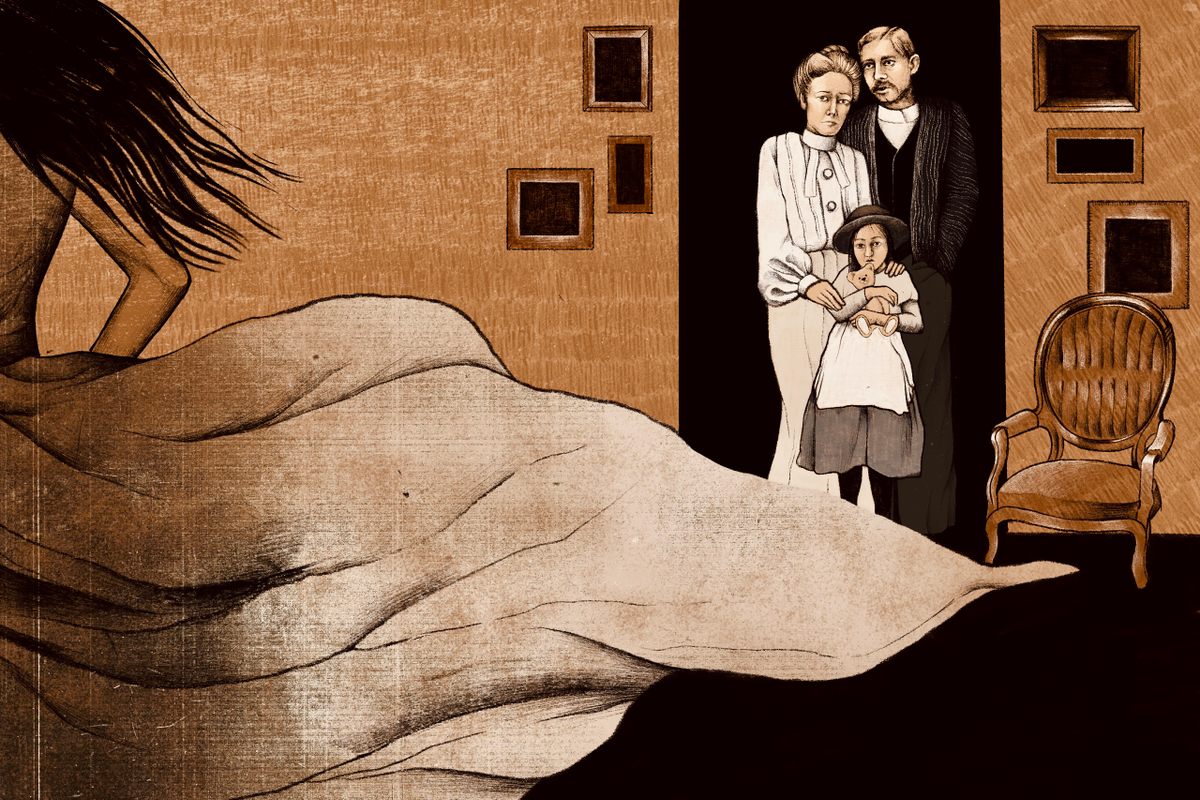

The story of what happened to the Bell family two hundred years ago is unsettling and terrifying, to be sure, but it lingers not just because it’s a good ghost tale, but because it’s built around a series of anxieties that have come to define much of American culture: about what happens when a patriarch loses control of his family, when religions come into conflict, and what takes place out on the borderlands between civilization and the wild.

The basic contours of the story have been fixed for at least a century, since the 1894 publication of Martin van Buren Ingram’s An Authenticated History of the Famous Bell Witch. According to Ingram, a mysterious series of events began to befall a prosperous farmer named John Bell in 1817. The Bell homestead was in Red River, Tennessee, an hour north of Nashville, near the Kentucky border in what is now the town of Adams. John and his wife Lucy had six children, including a daughter named Betsy who was 12 years old when the troubles began. One night in fall 1817, John Bell was walking through his corn field when he came across a strange animal, unlike any he’d ever seen. Assuming it was some kind of dog, he shot at it and it fled. Other disquieting events followed: His son Drew saw a strange bird soon thereafter, and Betsy reported seeing the body of a young girl in a green dress hanging from the trees in the forest nearby.

Whatever it was, it didn’t stay in the forests or fields. Strange sounds filled the house at odd hours, including mysterious knocking, the sound of rats gnawing at bedposts, dogs barking and snarling, and chains being dragged across the floor. Bedsheets were torn from sleepers, and pillows were jerked from beneath their heads. Eventually, the Bells began to hear a woman’s voice: the entity, it seemed, could talk, and she talked a lot. She knew scripture, and seemingly things about the family that no one else could know. At first a pleasant curiosity and devoutly religious, the entity soon turned sour: insulting John, trying to interfere with Betsy’s love life, gossiping, and spewing racist insults at the Black people the Bells enslaved. The entity became legend; everyone in Red River knew of the Bell’s resident spirit, Ingram’s telling explained, and visitors came from all over to bear witness, including war hero and future president Andrew Jackson, who spent a night with his men attempting to draw out the spirit.

Though she was happy to entertain or torment visitors like a tourist attraction, her most singular, consistent attribute was an abiding hatred of John Bell. While she was (perhaps surprisingly) exceedingly kind to Bell’s wife, she heaped abuse and scorn on the homestead’s patriarch for years, tormenting him until he grew sick and frail. In December 1820, John came down with what would be a final illness. His attending doctor discovered a mysterious vial half-filled with a dark-colored liquid. Upon the discovery of this vial, the chatty Bell Witch crowed triumphantly, “It’s useless for you to try to relieve Old Jack, I have got him this time; he will never get up from that bed again.” Referring to the vial, she affirmed, “I put it there, and gave Old Jack a big dose out of it last night while he was asleep, which fixed him.” John Bell died the next day.

After that, the witch seems to have mostly left the Bells alone, its primary goal accomplished. It popped up sporadically thereafter, but never anything close to the sustained terror it visited on the family’s patriarch. It is the death of John Bell that makes the story of the Bell Witch so distinctive; rarely does a supernatural story like this result in a fatal physical impact on a human being. Ghosts simply don’t commit murder—and it is due to this unusual aspect to the legend that has led people, for decades since, to try to figure out exactly what happened, and why.

“Hauntings” and the stories they spawn require some kind of supernatural explanation, and over the years, many of them end up getting real-world explanations, too: mental illness, a desire for attention, natural phenomena misinterpreted. The case of the Bell Witch stands out for its lack of explanation on either count: There’s a marked lack of a consistent narrative for why the Bell family was so plagued and no simple moral for audiences a century later. The Bell Witch herself offered up any number of explanations, while dismissing them all. At one point she told the family, “I am the spirit of a person who was buried in the woods nearby, and the grave has been disturbed, my bones disinterred and scattered, and one of my teeth was lost under this house, and I am here looking for that tooth.” But when John pried up the floorboards in search of the lost tooth, the witch laughed at him, claiming the whole thing was a joke. The Bell Witch kept changing her story.

Other than its desire to harass and ultimately murder John Bell, the witch was also invested in interfering with young Betsy’s love life. At the time she was being courted by a young man named Joshua Gardner, to whom the Bell Witch took an instant dislike. According to Ingram’s An Authenticated History, the Bell Witch would often warn Betsy, pleading in a “soft melancholy voice,” that Gardner was to be avoided, cooing to her, “Please Betsy Bell, don’t have Joshua Gardner. Please Betsy Bell, don’t marry Joshua Gardner.” But, as with the rest of its motivations, the witch never made her reasoning clear.

At one point, one of her interrogators, Reverend James Gunn, got a name out of her: Kate Batts. Batts, a woman who lived in Red River, was sometimes described as the “witch’s human exponent,” and was known in town as “a big woman, strident and coarse.” But the witch then immediately denied that she had any connection to Batts—and yet, from then on she answered to the name Kate. And so, by the end of Ingram’s story, it’s not at all clear whether the malevolence came from a living witch, or a ghost, or some other supernatural entity: The narrative frustrates by repeatedly offering hypotheses that it then goes out of its way to discount.

As such, modern tellers of the story have put their own spin on it. In addition to the films and books, dozens of paranormal podcasts have devoted episodes to the Bell Witch, and nearly every one of them offers a different explanation. Some insist that the Bell farm was on Native American burial ground—a standard trope, almost exclusive to white Americans, as a way of engaging with the Native American genocide while keeping it at arm’s length. Another popular interpretation focuses on a schoolteacher named Richard Powell, who supposedly wanted to marry Betsy Bell when she was a teen. He is said to have summoned the Bell Witch to haunt the family after being rebuffed by Betsy and her father—an explanation that plays up Betsy’s vulnerability in a world of toxic, abusive men. Others conclude that Kate Batts, as an unpleasant (by all accounts) and unmarried woman, was a scapegoat, a version that taints the story with misogyny.

These are, at best, conjectures, and none of them feels definitive. It’s hard not to be frustrated, because we’re hardwired to want answers. Ghost stories are stories, after all, and we want them to carry some kind of meaning, message, or moral. Is there one in the tale of the Bell Witch? As with many things haunted, sometimes you have to go beneath the floorboards for an answer.

Every retelling of the Bell Witch story relies on the same source text: Ingram’s 1894 book. The story had floated around as an urban legend in northern Tennessee for some time, but it never left the region until Ingram found it and popularized it. An editor at the Clarksville Leaf-Chronicle, he had traveled to Adams (then Adams Station) in 1892 to report on the tobacco crop there and to visit “the grounds where historic and most intensely thrilling events were enacted seventy-five years ago,” as he reported in one dispatch. Upon returning, he worked his findings into a book, ultimately quitting his newspaper job so he could work on it full-time. According to Ingram, he worked off an unpublished manuscript by Richard Williams Bell (son of John), titled Our Family Trouble, and a transcription of the manuscript makes up the bulk of the book. But Bell’s supposed source text itself has never surfaced, and in the absence of other evidence, it seems likely that Ingram ghost wrote Our Family Trouble himself.

In recent decades, as interest in the story has intensified again, more and more historians and amateur sleuths have tried to track down sources that predate Ingram’s book. So far, only a few enigmatic leads have surfaced. One is an article from 1849 that appeared in the Saturday Evening Post, in which the writer recalls a story of the “Tennessee Ghost” or “Bell Ghost,” concerning a farmstead in Robertson County, Tennessee. As the unnamed author recounts, the Bell household (here, the daughter’s name is spelled “Betsey”) was visited by a spirit every night, only when the lights were out, and conversed freely with the Bells and anyone else around. Asked how long it would stay in the house, this ghost replied, “Until Joshua Gardner and Betsey Bell get married.” (This, of course, is the opposite of the witch’s intention in Ingram’s telling.) Eventually, in the Post story it is revealed that Betsey had been using ventriloquism to simulate a haunting, and the ghost, so exposed, “vanished into thin air.” The promised marriage never came to fruition. This story echoes the only known contemporaneous record, from an officer named, strangely, John H. Bell, who was traveling through Robertson County in 1820. He also recorded the story of a 15-year-old girl who attempted to use ventriloquism to get a neighbor to marry her; while he himself had no involvement beyond record the story he’d heard, it was his name that ultimately got attached to the legend as it mutated through the decades.

According to the Saturday Evening Post writer, many in Tennessee were “well acquainted” with the story, and it seems easy in hindsight to see how Ingram took this kernel and adapted it to his An Authenticated History, inverting the witch’s attitude toward the union of Betsy and Joshua Gardner, and turning a grounded, if odd, story into something much more menacing and mysterious. Ingram, much like the directors of The Blair Witch Project, knew that something passed off as true will always be more terrifying and alluring than fiction, and he stuffed his book with a number of rhetorical tricks to convince the reader that its contents were true. (He even included an unsubstantiated claim that Betsy Bell sued the Saturday Evening Post writer for libel.) Just as the directors of the movie used shaky camera footage, he included letters from people who remembered the incident, and the unpublished and unavailable “diary” of a Bell son. (“Found” documents of a haunting seem to be an enduring trope.)

But if the narrative itself doesn’t reach a definitive conclusion, the concerns that underlie it come through clearly. An Authenticated History appeared at a key moment in American history, and even as its events take place in the early 19th century, the story itself reflects a set of anxieties that had become acute by the 1890s—anxieties that continue to resonate to this day.

For Ingram’s book, even if it was largely fictional, wasn’t written in a vacuum. The year 1894 was a momentous time, which many saw as a turning point in American history. The previous year, the World’s Columbian Exposition had opened in Chicago (commonly called the Chicago World’s Fair). Meant to celebrate the 400 years since Columbus’s arrival in the Western Hemisphere, its organizers saw it as a grand celebration to symbolically bridge the continent’s earliest interaction with European settlers and its future to come.

Historian Frederick Jackson Turner, however, saw the moment as the end of an era, of a way of life. At a special meeting of the American Historical Association held at the Chicago’s World Fair, Turner delivered a lecture and accompanying essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” It was a shot heard ‘round the country that radically changed how many saw their American identities. It’s not possible to understand the story that Ingram was trying to tell about the Bell Witch without understanding first the context of the time, a time informed heavily by Turner’s ideas.

For Turner, the 1890s was when Anglo Americans saw the frontier as something that had closed, and with that came a renewed interest in what that frontier had meant. His essay began with a finding from the 1890 census report, that the American “frontier,” a line separating “civilization” from the “unsettled,” no longer existed. This, Turner claims, “marks the closing of a great historic moment.”

Turner contrasted two kinds of Americans: those in the East, whose culture remained deeply informed by European customs and ideals, and those on the frontier, who embodied a new kind of American identity. What had come to be known as an “American,” he argued, was more shaped by the experience on the frontier. (As probably goes without saying, Turner’s concept of an “American” was a white man, first and foremost.) As he explained, “the frontier is productive of individualism. Complex society is precipitated by the wilderness into a kind of primitive organization based on the family. The tendency is anti-social. It produces antipathy to control, and particularly to any direct control.” Turner saw this arrangement of social life—into autonomous family units—as vital to the American project: “The frontier individualism has from the beginning promoted democracy.” It was the frontier, he argues, that allowed America to embrace Jacksonian democracy—the shift in political participation from land-owning elites to all white men, and with it a belief that the people are sovereign and that the government exists to carry out their will.

A careful reading of Ingram’s book reveals how informed he was by this ideal. The opening of An Authenticated Story could have come straight from Turner: “More than one hundred years ago, the Star of Empire took its course westward, following the footprints of the advance guard who had blazed the way with blood, driving the red man, whose savagery rendered life unsafe and civilization impossible, from this country, then, as now, teeming with possibilities.” Northern Tennessee was, by Ingram’s time, settled land, but he cast the Bell homestead as an outpost on America’s wild borderland, where good men and their families brought order and commerce to a place of “savagery.” “The land of milk and honey had been discovered in Tennessee, then the far west,” Ingram writes, “and the flow of emigration from North Carolina, Virginia, and other old states, became steady and constant, rapidly settling up the country.” Andrew Jackson’s appearance in the legend, as a war hero–turned–amateur ghost hunter, would seem to further cement Ingram’s debt to Turner.

John Bell, like the other settlers of Red River, is held up by Ingram as a perfect representative of Turner’s frontier Americanism. Of the town’s founders, he writes that they “raised large families, and formed the aristocratic society of the country, and no man whose character for morality and integrity was not above reproach was admitted to the circle. The circle, however, widened, extending up and down the river, and into Kentucky, embracing a large area of territory. Open hospitality characterized the community, and neighbors assisted each other and co-operated in every good move for the advancement of education and Christianity.” The John Bell of Ingram’s book is the archetypal American, a figure who gets ahead through industrious hard work, builds a homestead and a family on the edge of civilization, domesticates the land, and raises a successful family.

And yet, somehow everything goes wrong; Bell watches helplessly and haplessly as his family is plagued by unseen forces and slowly torn apart—a frontier American Job. An Authenticated History is, if nothing else, the story of American masculinity in crisis. John Bell cannot protect his daughter, and he cannot protect himself. A female spirit—ghost or witch or otherwise—torments him and imperils his daughter, while, in a final emasculating gesture, being perpetually kind and complimentary to his wife.

And while An Authenticated History never quite reveals what’s behind the haunting of the Bell homestead, Ingram suggests that the witch was made malevolent by an attempt to reconcile the town’s Baptist and Methodist communities. Initially she is an astute and sober quoter of scripture, who, Ingram tells us, always “held fast to Christianity,” but her attempt to blend these two faiths proves too much, “even for so great an oracle” as the Bell Witch, and “the mixture was too strong for the Witch’s faith, and the whole stock of piety was soon worked out at a discount.” Soon after she backslides from her faith, becoming vengeful and turning on the Bells, John most of all. Ingram’s book is a cautionary tale, one that suggests that rugged individualism isn’t enough on its own, that attempting to tame the frontier without orthodoxy and tradition will unleash nightmares.

While Turner’s embrace of the frontier as a breeding ground for Jacksonian democracy may seem antiquated now, the Bell Witch narrative endures because the “frontier” remains a fraught site for white America. It might be called “the border,” but it is more of an ideological space, an imaginative landscape where rugged individualism is bound to political identity. We must, many Americans continue to tell themselves, secure that space and that identity, and defend the American project from the scary things on the other side. This cannot be done, these people suggest, without holding fast to tradition. The story of a patriarch who has lost control of his family, beset by a malevolent spirit in the form of a woman unattached to another man, who emasculates him and threatens his daughter—all of this seems to mirror contemporary conversations about family, gender, and feminism. The Bell Witch is powerful, unhindered by men, and therefore terrifying. Turner, Ingram, and the Bell family are gone, but their story remains where legions of white men define themselves by a border or frontier, where straying from orthodoxy is a path to ruin.

This complexity could be why we can’t look away from the story of the Bell Witch amid all the other ghost stories that drift in and out of the American consciousness. Storytellers look for explanation, resolution, clarity. The only clarity in the story of the Bell Witch and its endurance over more than a century is the way it taps into white, male American anxieties, anxieties that are of culture’s own making.

This is also why such stories endure, and why they continue to haunt us. A good ghost story terrifies because it leaves something unsettled, unanswered, unfinished—it’s that lack of a definitive answer that often leaves us coming back, as we try to make sense of it and shudder at the thought that we can’t. But a good ghost story resonates because it taps into the cultural anxieties all around us, which is why they’re always worth listening to: They offer a space to (safely) inhabit those fears, exploring them while telling ourselves all the while: “There’s nothing to be afraid of.”

* This story was updated to make it clearer that the Bell Witch was among several legends that contributed to the Blair Witch mythology.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook