The Indigenous Canadian Work of Art with a Life of Its Own

The Witness Blanket, which honors survivors of cultural genocide, has the legal rights of a living entity.

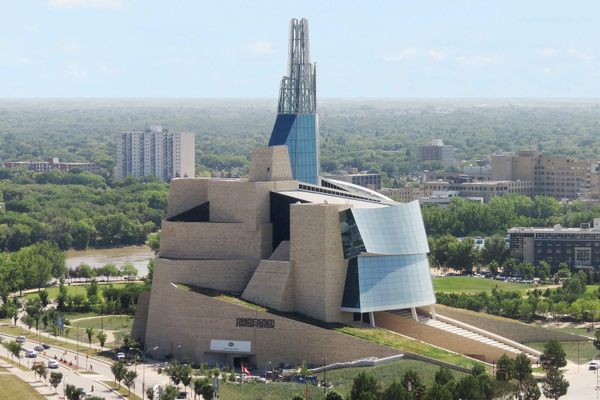

Along the shores of the Red River in Winnipeg, Manitoba, the Canadian Museum for Human Rights is a tower of curving glass, steel, and alabaster, a bright place even in the dead of winter. In a gallery on the first floor, conservator Stephanie Chipilski checks equipment that monitors the room’s temperature and humidity. She slips on a pair of gloves and approaches a curving 40-foot wall of cedar that displays hundreds of items, many mounted on wooden blocks. The fleece-lined leather tongue of a worn hockey skate has slipped out of place. Chipilski uses a tiny spatula to tuck it back into the boot.

She looks over the items surrounding the old skate: a statue of the Virgin Mary, draped with red cloth and inscribed with Cree syllabics; a ceramic lightbulb socket with a dangling pull-string; two braids of thick black hair. They are more than just a beautiful jumble of ephemera. This is the Witness Blanket, an unprecedented work of art with the legal rights of a living entity, and Chipilski is part of the team responsible for its unusual care.

“I’m very humbled to be a part of this. It’s a huge responsibility that shouldn’t be taken lightly,” Chipilski says. “The art piece and what it represents, it’s helped me as a Canadian learn.”

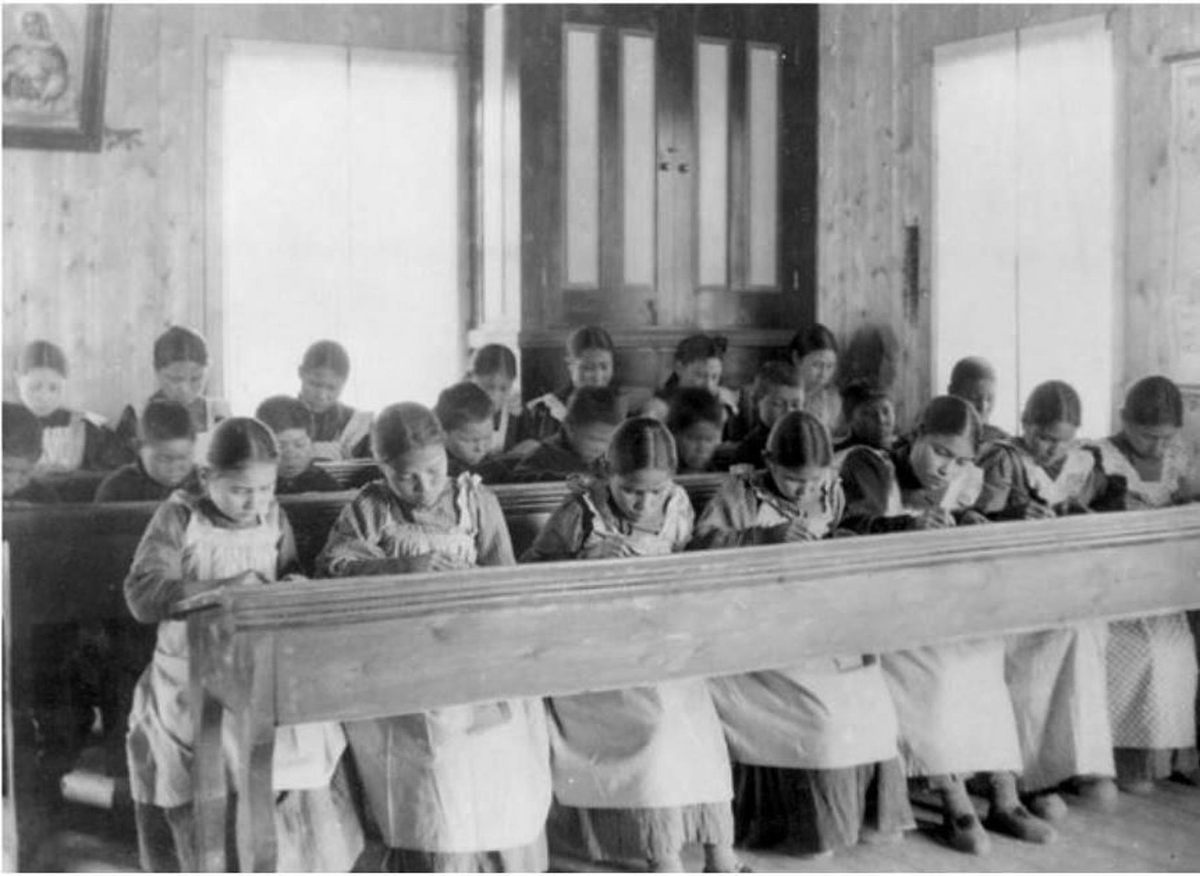

According to Canada’s National Center for Truth and Reconciliation, beginning in the 19th century, more than 150,000 Indigenous children were taken from their families to Indian Residential Schools for the purpose of assimilating them into white society, a campaign described as a system of cultural genocide. At least 6,000 children died at the schools, the last of which was closed only in the late 1990s.

Carey Newman, the artist behind the Witness Blanket, is the child of a survivor; his father was taken from his family at age seven. Newman created the project in his honor, assisted by a team that combed the country in search of items that spoke both of a painful past and the spirit to survive it. The team would collect more than 850 artifacts—bricks, a battered door pulled off its hinges, the wooden keys of a piano—each telling the story of a particular person, time and place.

Rosy Hartman joined Newman early as project coordinator and remembers finding herself, on a warm June morning in 2013, in the small Yukon town of Carcross, just north of the British Columbia border. Hartman was visiting the site of every former Indian Residential School across Canada, talking with survivors and collecting artifacts to display. In Carcross, she and her guide, a survivor named Harold Gatensby, whacked through thick brush, working their way toward the charred remains of a building. Broken glass, rusted bed frames and metal railings, twisted from the heat of a long-ago fire, were scattered around the site. Something caught Gatensby’s eye. He pointed into a thicket of trees. Hartman followed his gesture and, beneath a bush, found a small child’s shoe. The brown leather curled with wear and age. Moss and lichen clung to its sides. The eyelets were tarnished and green.

Excited by the find, one of the first pieces she collected, Hartman packed it up to take to Newman’s workshop. That night at her hotel, she had a nightmare. She woke as if running, tangled in her bedsheets, frantically trying to escape from something chasing her. When she returned home that week, suitcases of artifacts in tow, her partner also woke in terror from the same dream. Years later, the incident is still fresh. Says Hartman: “I just knew in my heart that it was that shoe.”

Hartman remembers taking the shoe to the workshop early the next morning, eager to have it out of her home. That evening, Newman sat with it and felt waves of anger, sadness, and fear rise from the worn leather.

“I did what came to my heart, which was to speak. So I spoke out loud about what I was doing, what the project was about, and I held it and I wept,” Newman says, adding that, as he did so, he felt its energy change. Newman’s Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw traditions teach that objects can have agency. Ceremonial masks and traditional big houses, for example, hold the spirits of ancestors and must be treated with the utmost respect. But until he held the shoe in his hands, Newman says he hadn’t given the same consideration to the objects collected for the Witness Blanket. The experience came to shape the rest of the project, and even its conservation plan.

Unveiled in 2014, the Witness Blanket went on a cross-country tour through 2019. While traveling exhibits often end up sold to, and on permanent display at, a museum, the Witness Blanket would have a different fate. Stemming from his experience with the shoe, Newman entered into an unprecedented legal agreement with the Canadian Museum for Human Rights: The Witness Blanket would have the rights of a living human entity, its guardians responsible for acting in its best interests.

In contrast to conventional art conservation, the guiding philosophy of the caretaker team is to preserve the spirit of each artifact, but not necessarily its physical state. Although the wooden frame and display blocks of the exhibit can be repaired when needed, the artifacts themselves will be allowed to age slowly but purposefully.

“There is a humility to this approach, it’s not meant to be forever,” says Newman. He hopes that one day the Witness Blanket will no longer be needed, its story of Canada’s residential schools and colonialism replaced by joyful tales of Indigenous resilience and resurgence.

At the Witness Blanket’s permanent home in Winnipeg, Chipilski and other conservators focus on controlling the environment around the exhibit rather than the artwork itself. And, while touching museum art is generally prohibited—dirt, salts, and oils on skin can degrade fragile material—the Witness Blanket team believes that gentle physical closeness may help people connect with the objects more. Panes of acrylic protect particularly delicate pieces, like the shoe, but all items are exposed to air circulating in the room around them so that visitors can feel their emotional energy. “Conserving the spirit of the objects of the blanket, that’s really what we’re preserving through this project,” says Newman.

Today the shoe looks much like it did the day Hartman first picked it up in Carcross. Surrounded by healing sweetgrass and sage, and cradled by strips of traditional red medicine cloth, it continues to tell its story.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook