The World’s Fastest Glacier Is Loud, Dangerous, and Transfixing

For those in the Greenlandic town of Ilulissat, it’s also an enchanting neighbor.

Visitors to Greenland’s Ilulissat Icefjord are greeted by an unnerving sign. “EXTREME DANGER!” it warns, “Do not walk on the beach. Death and serious injury might occur. Risk of sudden tsunami waves, caused by calving icebergs.” The source of the danger lies over 30 miles away, deep inside the fjord. There, 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle, Sermeq Kujalleq hurls icebergs into the sea. Glaciologists suspect the glacier calved the iceberg that sank the Titanic in 1912. Today, Sermeq Kujalleq—which is Greenlandic for “southern glacier”—still slithers along the same rocky fjord, threatening faraway ships and luring onlookers into its icy reaches.

Sermeq Kujalleq, also called Jakobshavn glacier, is known as the world’s fastest glacier. Like rivers, glaciers are constantly flowing, pushed forward by the weight of their own ice. This one travels an average of 130 feet in 24 hours and calves more than 11 cubic miles of icebergs each year into the Ilulissat Icefjord. If melted, those icebergs could provide enough drinking water for everyone in the United States for a year. Sermeq Kujalleq has grown and shrunk for centuries as part of the Greenland ice sheet. Formed over 250,000 years ago, the ice sheet today stretches 1,500 miles long by 680 miles wide and covers 80 percent of Greenland. Most of the ice sheet is ringed by mountains. Glaciers that lie along the coast, including Sermeq Kujalleq, therefore function as outlets through which ice and water from the ice sheet come gushing out.

The Ilulissat Icefjord is crowded with bergs thanks to Sermeq Kujalleq’s prolific calving and a quirk of geography. An underwater mountain, created by the glacier long ago, stands at the mouth of the fjord and traps the icebergs until they melt or break apart into smaller pieces. Some of those bergs are as tall and blocky as skyscrapers. Others look like castles with spires and bridges. In between, small icebergs known as bergy bits and other chunks of floating ice known as growlers churn like packing peanuts.

It takes the eye a minute to perceive that these icy masses are slowly moving. Wilhelm Gemander relocated to Greenland from Germany in 1985 and now operates a tourist boat out of Ilulissat. All these years later, he says, “I am still fascinated [by] the magnificent icebergs, the mountains, and the sea.” And he’s not the only one enchanted by the constantly changing landscape. Spectators hike along the fjord to take in the view. One local named Uffe Bang insists that the trails are not just for tourists. Bang takes time at least twice a month to visit and guessed most locals took advantage of the scenery—certainly the hunters who head into the fjord for days with sled dogs or snowmobiles.

Abundant fish in the fjord have long attracted people to the small meadow that hugs the rugged coast. In the Stone Age, the Saqqaq people lived at the mouth of the fjord at Sermermiut, followed by the Dorset and Thule peoples. European whalers arrived in the 16th century and established a nearby trading post in 1741 in Disko Bay that would become the colony Jakobshavn. Around 1850, the last people moved from Sermermiut to the colony. Jakobshavn, today known as Ilulissat or “icebergs” in Greenlandic, remains dependent on fishing in the icefjord. At 4,500 people (and 3,500 sled dogs), it is the third biggest city in Greenland and the country’s most popular tourist destination—thanks to Sermeq Kujalleq.

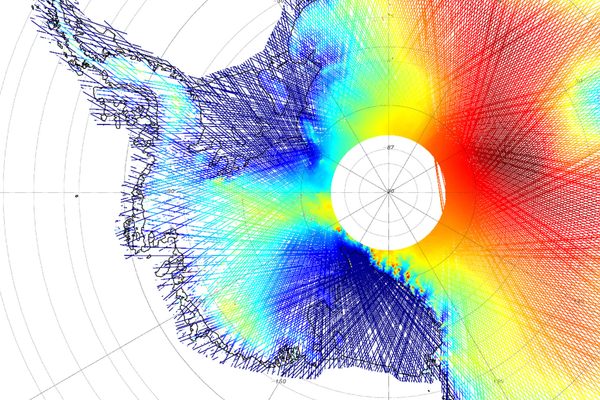

For hundreds of years, the bulk of Sermeq Kujalleq sat inland as it narrowly snaked between the dark grey gneiss and granite mountains lining the fjord. From space, the frozen projection looked like a hissing tongue protruding seaward. Glaciologists call such long, narrow ice streams “floating tongues” when they sit above the water, like the one protruding from Sermeq Kujalleq. During the Little Ice Age, when temperatures plummeted and the Vikings vanished from Greenland, Sermeq Kujalleq stretched more than 25 miles toward Disko Bay. Since 1850, it has been receding. From 1902 to 2001, the glacier withdrew eight miles; the following 10 years, it retreated a remarkable nine. Now the glacier lies tongueless on the seabed at the terminus of the fjord.

Even without a tongue, Sermeq Kujalleq is loud. Its front is an enormous ice wall—stretching 300 feet at its peak, or as tall as the Statue of Liberty—that constantly explodes. Icebergs break off the glacier accompanied by blasts and roars akin to a rocket launch. When they hit the sea below, the calved icebergs can create huge waves that threaten to swallow people, boats, and buildings. The icebergs from Sermeq Kujalleq have crashed so violently that they have even caused earthquakes. For nearly a decade, the Ohio State University glaciologist Santiago de la Peña has observed the glacier. Like many who have witnessed a calving event, de la Peña describes the experience as transfixing. Because the glacier is so large, the break seems to occur in “slow motion.” It is almost easier to feel, he explains. The whole glacier “creeps and rumbles,” he says, “you can feel its power, feel that it is enormous.”

After icebergs calve from Sermeq Kujalleq and pass over the submarine mountain, they float into Disko Bay. There, they are pushed north by the West Greenland Current. The icebergs swirl around Baffin Bay then head down the Eastern Coast of Canada. Most get trapped in sea ice or run aground in shallows along the way and never make it through “Iceberg Alley,” the stretch of the North Atlantic between Newfoundland and Greenland. Those that do ride the Labrador Current south into the wider Atlantic Ocean. Some icebergs from Greenland make it all the way to the subtropical Azores, menacing transatlantic shipping lanes.

Although the icebergs it produces can still slice through steel hulls, Sermeq Kujalleq’s greatest threat may be more abstract. Its beauty is attracting more tourists to Ilulissat each year. Vijayanthi Gemander, who runs the popular Inuit Café, initially planned her establishment as a small dessert and coffee shop in 2011. There wasn’t a need for anything else, she says. Now, she is working overtime to feed reindeer, muskox, whale, and halibut to the flood of visitors. Almost everyone in town claims the tourism industry exploded after the icefjord was made a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2004. In 2000, 6,304 overnight guests visited Ilulissat. In 2018, that number grew to 28,499. And while such growth may be a boon to the local economy, it has more complicated consequences for the environment. Besides more crowded hiking trails and additional waste, increased travel to Greenland means greater carbon emissions, which translates to a warmer planet and more vulnerable glaciers.

Glaciers around the world are melting before our eyes. In the latest turn in its long history, Sermeq Kujalleq has actually grown since 2016 thanks to a dip in temperatures in Disko Bay. Glaciologists describe it as an “interruption” in the long-term trajectory of retreat and the latest satellite data from 2019 suggests Sermeq Kujalleq has already lost what it gained. No matter the melt rate, the glacier is so large, de la Peña notes, “it will likely continue calving icebergs for hundreds of years.” It may be best to encounter the glacier in one its glimmering bergs closer to home rather than travel all the way to Ilulissat. But it is hard to resist the lure of Sermeq Kujalleq. “It is a place that is good for the soul,” says Ilulissat resident Casper Malchow. “Alone on the mountain with huge icebergs in the background and the sounds of whale playing in the icy water, it does something to you.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook