Basilica of St. John

This crumbling medieval basilica once attracted pilgrims by the thousands to collect a miraculous dust that formed above the saint's tomb.

The early Christian community in the ancient port city of Ephesus traced its origins to the apostle and evangelist St. John, the so-called Beloved Disciple. According to church tradition, John wrote his gospel in Ephesus, and, after a period of exile on the island of Patmos during which time he wrote the Book of Revelation, returned there and died.

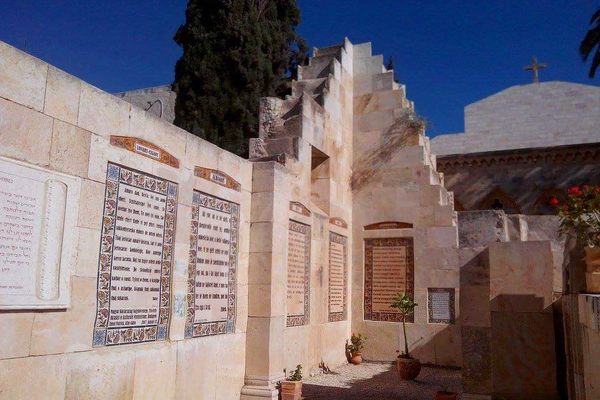

An apocryphal tale claims that John’s prayers shattered Ephesus’ Temple of Artemis, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. Ironically, the 6th-century basilica dedicated to St. John, built in Ephesus by the Emperor Justinian, would become one of the wonders of the medieval world. Built on the supposed site of the saint’s tomb, the church formed part of a building program that included the massive Hagia Sophia in Constantinople and the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna.

In its medieval heyday, the basilica was a major pilgrimage site, sitting directly on the overland route to the Holy Land. The architectural icon of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice copied the design of St. John’s, which like its Venetian counterpart was lined with gold mosaics depicting saints and gospel stories. Now-lost relics once held in the basilica included a piece of the True Cross that John carried around his neck, a garment worn by the saint made by the Virgin Mary, and the original manuscript of John’s Book of Revelation.

The church’s major attraction was, of course, St. John’s tomb, and its marble encasement is still visible today. An old story relates that when the saint’s tomb was opened by Constantine, no relics were found, attesting to the saint’s miraculous assumption into heaven.

Another account claimed the saint was sleeping beneath the tomb, and his breath stirred a fine ash, called manna, to form upon the tomb. This latter tale attracted thousands of pilgrims to the tomb each year on the saint’s feast day, May 8, to collect some of the holy manna for themselves. One of these pilgrims was the 13th/14th-century Catalan mercenary Ramon Muntaner, who claimed to have personally witnessed the ash bubbling up over the tomb. He wrote that the manna could cure both fevers and gallstones, that it could calm a storm when tossed in the sea, and could induce birth in a woman when consumed with wine.

Today most tourists stroll past the remains of St. John’s basilica on the way up scenic Ayasuluk Hill and its imposing Byzantine-Turkish fortress. Piles of brick and marble, crumbling columns and wayward capitals sketch a skeleton outline of what was once one of the most sumptuous houses of worship in the world. After the Oghuz Turks conquered Ephesus in the 14th century, the church was briefly converted to a mosque—soon earthquakes forced the abandonment of the crumbling relic.

Know Before You Go

The basilica is a short walk from the center of Selçuk. The entrance is off St. Jean Caddesi. The site is open from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. April to October and 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. November to March.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook