Camp Atterbury Prisoner of War Chapel

A chapel built by Italian POWs during World War II tells a forgotten tale of the war on the home front.

Camp Atterbury, today an active National Guard base in south central Indiana, was built as an army training facility shortly after Pearl Harbor, and soon became the unlikely destination for about 15,000 POWs from Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler’s armies.

The prison section of the camp, now a county park and fish and wildlife area, housed enemy combatants throughout World War II. In 1943, some Italian soldiers were given permission to build a tiny Roman Catholic chapel in a quiet corner of the camp.

Hidden away in this remote place, the remains of the POW chapel tells a quiet, if cryptic, tale about the other side of war.

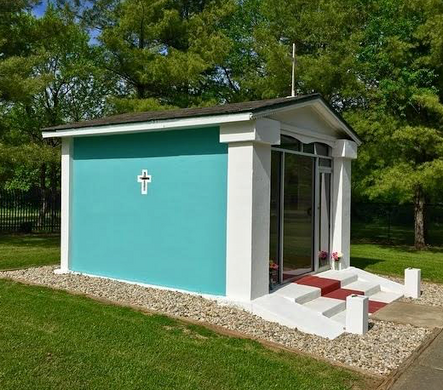

Prisoners weren’t allowed to use valuable construction material, so the chapel turned out to be a low-key affair, measuring just 11 by 16 feet. The Italians used leftover brick and stucco. When it came to painting the ceiling and walls, rumor has it that they used flowers and berries from the nearby marshes and woods as well as their own blood to create pigments. A U.S. Army chaplain, Maurice Imhoff, held mass on Sundays.

This humble chapel hobbled together out of cast-off building materials is a pale shadow compared to the architectural wonders of Italy. Yet its wholly unexpected presence in rural Indiana attests to a forgotten, fascinating episode of World War II on the home front.

Many Americans may be surprised to learn that during World War II, tens of thousands of Axis soldiers came to the United States. Only a handful of them, however, came as combatants. Most lived here as prisoners of war, interned at POW camps in remote parts of the country.

The existence of the World War II prison camps was discouraged from becoming headline news. But the U.S. Army established about 175 of internments throughout the country. In the 1940s, the largest number of the U.S. army’s prisoner camps, set up to hold German and Italian prisoners captured in Europe and North Africa, were located in Wisconsin and Texas. (The idea of locating POW camps in the Midwest didn’t originate with World War II. During the Civil War, the Union army had incarcerated thousands of Confederates on Northern soil, most notoriously at Elmira, New York, dubbed “Hellmira.”)

Some of the WorldWar II camps were designated as “segregation camps,” used to incarcerate particularly hardcore Germans, ones who had been more indoctrinated by Nazism than the average rank-and-file soldier. (Some Axis soldiers had actually been forced into Hitler and Mussolini’s armies by death threats.) However most of the POW camps in the U.S. held enemy combatants not considered especially dangerous to Americans.

Conditions at Atterbury were not exactly harsh. In fact, POWs often preferred American incarceration to what they’d gone through in Europe. Nineteen prisoners (three Italians and sixteen Germans) died of sickness and wounds, and were buried at a small POW cemetery on the grounds. (Their bodies were moved to Camp Butler in Springfield, Illinois, in 1970.) For many prisoners, however, life at the POW camp was relatively pleasant.

The Germans and Italians at Camp Atterbury mostly worked as groundskeepers, cutting wood, hauling brush, doing laundry and cleaning. Inmates at Atterbury had access to three soccer fields, six volleyball courts, a boxing ring, a gymnasium, and three fields for playing bocce ball. A U.S. Army program allowed some POWs to work off-site on nearby Hoosier farms and in factories. Indiana farmers could actually request their labor.

A news article from 1943 reported that “On their arrival at Atterbury, many of the prisoners could not understand how they got to India. They believed that Indiana was a part of India. Some expressed wonder at how New York City could have been rebuilt so quickly. They had the impression that New York had been destroyed by bombs. When asked what they desired to be put in stock in their canteens, they were unanimous in requesting suspenders, hair oil, hair tonic, facial creams and hand lotions.”

A German soldier, Peter von Seidlein, who was captured in Normandy just after D-Day and sent to Indiana, recalled 40 years later: “When I was working with a detail cutting trees in the winter of 1944-45, we once spent much time in a deserted 19th century farmhouse. I always wondered what became of the farmers… Life in the POW camp was heaven. We received a new U.S. Army outfit, got as much to eat as we could eat and slept in a bed with a mattress.”

Abandoned after the war and assailed by the elements, the seriously deteriorated “Chapel in the Meadow” was restored in the 1990s, partly with the help of the Indiana Italian Heritage Society.

In 1999, the chapel was damaged by an arsonist claiming retaliation against the Federal government for the assault on the David Koresh compound in Waco, Texas. The structure was saved by firemen, and today you can still see a few small murals of Jesus and the Virgin Mary, chubby-cheeked cherubs, angels, and a dove representing the Holy Spirit. The altar is painted to look like marble, and the chapel’s walls are a brilliant Mediterranean blue.

Know Before You Go

Camp Atterbury is about 45 minutes south of Indianapolis on I-65 or U.S. 31. A visitors center near the entrance to the National Guard base can give you the best directions to the POW Chapel, but if they're closed, take Hospital Road north into the Johnson County Park, then west through the middle of the picnic and camping area. Keep your eyes wide open, because the signs to the chapel can be hard to spot. The POW chapel sits on the far west side of the park near a fishing pond. It's the only building left out of about 100 that once made up the internment camp.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook