AO Edited

Manna of St. Nicholas of Bari

A dead saint, a deadly poison, and a mysterious holy ooze.

“I know I must die; someone has given me Aqua Tofana.” Mozart told his wife on his deathbed in 1791. Wolfgang was referring to an infamous poison, reputedly odorless and tasteless that was widely suspected of having killed hundreds of people in Italy a century earlier.

Aqua Tofana and its creator, a Sicilian lady named (maybe) Teofania de Adamo, are discussed as fact in a variety of early 18th century sources, but as the original story has blended with elaborate, macabre fiction it has become difficult to determine what, if anything, is the actual truth. The poison itself was described as a solution of arsenic, either as a light and delicate powder or a clear and odorless liquid, both deadly and untraceable. Vials of this stealthy poison were sold to the ladies of Rome and Naples for the purposes of dispatching inconvenient husbands. Before she was hanged for her crimes - accused of helping kill some 600 people - she allegedly passed on the deadly secret to her daughter, who went on distributing the poison, disguised in innocent looking delicate glass jars decorated with images of the Saint Nicholas of Bari.

St. Nicholas (better known to most in his modern incarnation as Santa Claus), was a 4th century bishop from the area of Myra, in modern Turkey. Like many very early Christian saints, very little is provably known about about his life, but his legacy is filled with stories of miracles and acts of good will, including his famous anonymous gift giving. When he died in 346, he was buried and his remains revered as holy relics. In the years after his death, his tomb was said to give off a sweet smell, and to weep a mysterious liquid which would cure those who touched it. Of course, pilgrims flocked to Myra for the privilege.

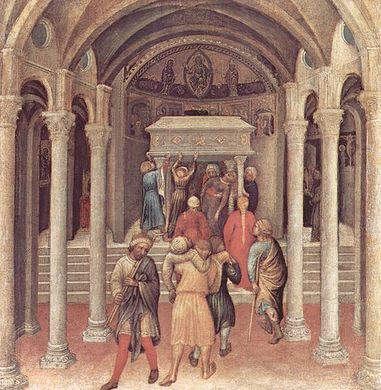

But then, after the conquest of Turkey by the Muslim Seljuq Turks in 1071, a plan was hatched to rescue the saint’s remains, and transport them safely to Christian territory in Southern Italy. In 1087 his relics were stolen and brought to Bari by a group of sailors, whereafter the relics were re-interred in a new basilica built for the purpose. Miraculously, after being placed in their new home in Bari, the new marble tomb also began to excrete the sweet smelling holy liquid, known as the Manna of Saint Nicholas.

This manna - described by early reports as an oil, but revealed more recently to be water - was widely believed to be a cure-all. For hundreds of years now, the manna has been collected, mixed with holy water and bottled in small glass vials decorated with icons of the saint for sale to pilgrims.

The bones and the manna production remained an undisturbed miracle until 1953, when restoration work at the basilica required the moving of the relics. A study was allowed and led by Luigi Martino, professor of human anatomy at the University of Bari. When the tomb was opened, the incomplete skeleton was found to be resting in a shallow pool of liquid. Studies revealed it to be that of a slight man in his 70s, matching the traditional story of St. Nicholas’ death at age 74. The relics were left on a linen sheet, which was seen to collect moisture even as the study continued. At the end of the construction in 1957, the bones were reinterred, where they have continued to weep manna.

For years there had been debate over the validity of relics also claimed as Saint Nicholas located in Venice. In 1992 Luigi Martino, the same anatomy professor who examined the relics in Bari, conducted an examination of bones claimed to be Saint Nicholas in Venice. While not reaching a formal conclusion, he determined that the bones in Venice were both similar and complimentary, and may in fact be different pieces of the same person. The explanation? The sailors from Bari were in a big hurry when they first took the relics, and may have only grabbed the bigger pieces of the skeleton, leaving bits and pieces for the Venetian crusaders to grab when they stopped by a few years later. The Venetian relics can be visited at the Chiesa di San Nicoló, Lido, Venice, Italy.

There are many theories about the origins of the manna, from fraud to a capillary action of the stone tomb sucking up ground- or seawater and redistributing it at the tomb. Whatever the case, the little bottles of manna traveled throughout the Christian world, a popular household item by the time the Aqua Tofana scandal emerged in the 1700s*.

It is fair to say that Italian women have been widely vilified as consummate poisoners. From Catherine de Medici to the Borgias in lurid romances involving mysterious deaths and wicked women, the poisoners were almost always Italian. For the most part, these claims seem to be wildly exaggerated, but it is still possible that there is a core of truth to the Aqua Tofana legend, as there seem to be firsthand reports. Either way, it is certain that the story traveled far and wide, and was largely believed to be true. By the time Mozart lay dying, it was commonly accepted as fact. In truth, although he may have feared that had been poisoned, odds are more in favor of copious bloodletting leading to his demise.

The collection of the holy Manna of St. Nicholas happens annually on May 9 in Bari, and his saint’s day is celebrated annually on Dec 6. The sailors who brought the saint’s body to Bari are buried around the church walls, and remembered in carvings around the exterior walls of Basilica San Nicola. The tomb of St. Nicholas is in the crypt. You can still purchase small glass vials of manna.

Know Before You Go

Five minute walk from Bari harbor

It is traditional for women to cover their hair before entering the church, but especially before entering the crypt.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook