Mono Lake

Aqueducts have dramatically changed this old lake, now home to tufa towers and its very own species of tiny brine shrimp.

Mono Lake is believed to have formed 760,000 years ago, making it one of the oldest lakes in North America. Researchers estimate that at the time of the last ice age, the lake was 900 feet deep and surrounded by large volcanoes. Islands in the lake were known as important nesting sites, and it is believed that 85% of California Gulls started their life there. All that changed, however, in 1941, when the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power built an aqueduct and began diverting the lake’s water 300 miles south.

So much water was diverted that the rate of evaporation far exceeded the inflow. Subsequently, the lake’s surface level decreased to half its depth while the saline levels doubled. By 1962, the lake had lost almost 25 vertical feet and its ecosystems began to crumble. The nesting beds became accessible to predators, mostly coyotes, and the famous California gulls were forced to abandon the site.

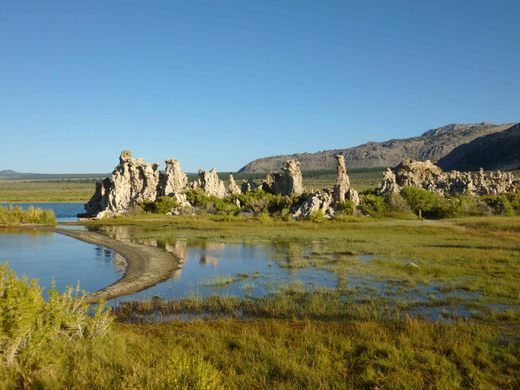

As the surface level dropped, it also exposed alkaline sands and odd-shaped tufa towers that had lain hidden for years. The tufa towers, which have since made the lake popular among tourists, are calcium-carbonate structures that form from underground springs. The calcium and carbonate mix to form limestone and builds up over time to create the 30-foot tall spire structures that can be seen today.

The lake was almost left to ruin until 1978, when David Gaines assembled the Mono Lake Committee and began spreading awareness about the urgent state of the area. A decade later, Gaines and his colleague, Don Oberlin, were killed on site in a winter automobile accident. Despite this tragedy, the committee has continued to fight to preserve the area, now known as an important ecological and geological site for researchers.

Though the lake’s hypersalinity and alkalinity levels make it impossible for fish to survive there, the area is home to a species of brine shrimp, Artemia monica, found nowhere else in the world. The brine shrimp – roughly the size of a thumbnail – lay dormant during winter months, but 4-6 trillion brine shrimp surface by spring time and early summer.

The tiny species of brine shrimp, as well as alkali flies, feed off even tinier species of microscopic, single-celled planktonic algae. The green algae reproduces rapidly during the winter months, and by March the lake is said to look “as green as pea soup.” Like any food chain, however, both shrimp and flies alike become a delicacy to millions of birds that flock to the area year round. Every fall, 1.5 million Eared Grebes stop to feast at Mono Lake during their long migrations.

Although the landscape has dramatically changed – and though the water levels still remain below the historic record – Mono Lake has one of the most productive ecosystems in the world and is a geological hotbed for researchers. Located in the Mono Basin, the area is the center of much seismic activity, and is flanked by volcanic rock formations that are 1-3 million years old. Such formations include the Mono Craters, 24 domes of explosive rhyolite that forms the youngest volcanic chain in North America.

Today, the Mono Lake Committee suspects that it will take roughly 20 years before the water will return to 6,392 feet above sea level, the Water Board-ordered stabilization level. Even then, the salt levels will be twice as concentrated as the ocean.

Know Before You Go

Highway 395, 13 miles east of Yosemite National Park, near the town of Lee Vining, California.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook