AO Edited

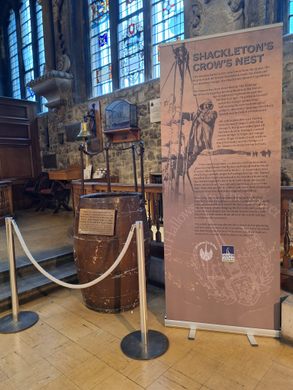

Sir Ernest Shackleton's Crow's Nest

The barrel-made lookout from Shackleton's final ship is tucked away in the crypt of one of London's oldest churches.

All Hallows-by-the-Tower is a church with a mysterious secret in the basement.

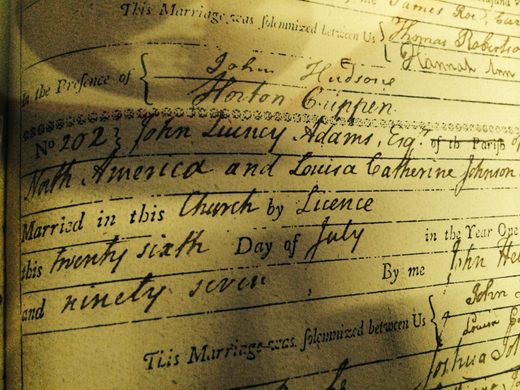

Founded in 675, and located just by the Tower of London, it is the oldest church in the City of London and is steeped in history. Samuel Pepys watched the great fire of London from its spire, noting “the saddest sight of desolation.” John Quincy Adams was married here, to local parishioner Louisa Catherine Johnson in 1797 while serving in London for the Washington administration, and in fact Louisa was the first First Lady to have been born outside the United States. Due to its close proximity to the Tower, most of the beheaded victims of the Tower’s executions were buried here. The pub next to the church is suitably called the “Hung, Drawn, and Quartered.”

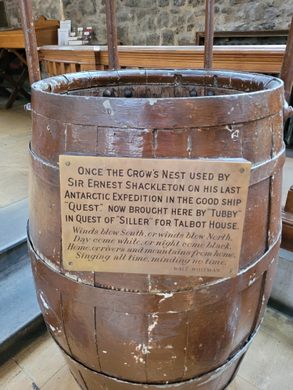

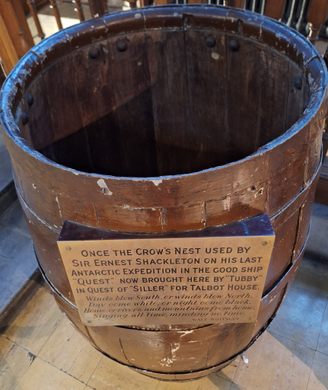

But hidden away in the crypt below the church is a peculiar artifact: the original crow’s nest from the ship Quest, which was the vessel that was fielded on Sir Ernest Shackleton’s final voyage.

By 1920, Shackleton was on the verge of obscurity. With nowhere near the legendary status he is viewed with today, and his star truly eclipsed in the minds of the British public by Sir Robert Falcon Scott, Shackleton was on the lecture circuit. While monuments were being erected all over Britain to Scott, Shackleton, drinking heavily, toured the country telling the tale of his doomed Endurance voyage, some three years before.

In 1921 Shackleton decided on another polar voyage. With funds drawn from his friend John Quiller Rowett he chartered a 125-ton Norwegian sealer, naming her Quest. His expedition’s goals were somewhat vague, but were loosely centered on exploring “lost” sub-Antarctic islands, such as Tuanaki.

The Quest was a schooner-rigged steam ship of 111 feet. With much of the same crew from the Endurance, the Quest left England on the 24th of September, 1921. Shackleton reached South Georgia by January, 1922, but by this time, his health was rapidly deteriorating. He’d already suffered a suspected heart attack en route, in Rio de Janeiro, but Shackleton continued drinking. In the early hours of January 5th, he summoned the expedition’s physician Alexander Macklin to his cabin.

According to Macklin’s retelling of the night, he told Shackleton that he had been overdoing things and should try to “lead a more regular life,” to which Shackleton answered: “You are always wanting me to give up things, what is it I ought to give up?” “Chiefly alcohol, Boss,” replied Macklin.

Moments later, Shackleton suffered a fatal heart attack and died in his cabin aboard the Quest. Emily Shackleton wired the expedition, requesting that her husband’s body be buried in South Georgia, where he rests to this day, in the remote Grytviken cemetery. Macklin recorded in his diary, “I think this is as the Boss would have had it himself, standing lonely on an island far from civilization, surrounded by a stormy tempestuous sea, and in the vicinity of one of his greatest exploits.”

The Quest survived World War II, working as a mine sweeper, but was eventually sunk by ice in 1962 off the coast of Labrador whilst on a seal hunting expedition. Shackleton’s original cabin was saved, as well as the crow’s nest, before the ship sank. The cabin ended up in Norway, with plans to restore it and send it to the South Georgia Polar Museum.

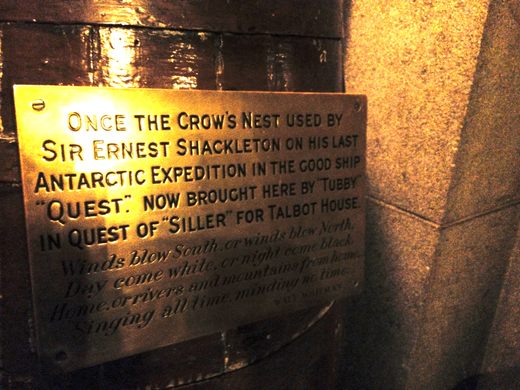

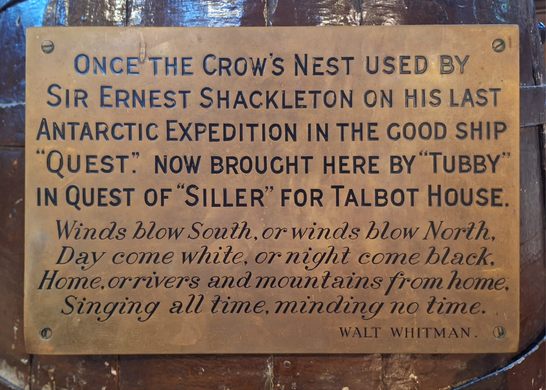

But the answer to the mystery of how the crow’s nest found its way from the frozen seas of north east Canada to a church crypt in London can be found on a plaque attached to it. It bears the inscription “brought here by Tubby in Quest of Siller for Talbot House.”

“Tubby” was the then-vicar of All Hallows, the Reverend Philip Clayton. Nicknamed “Tubby” whilst serving as chaplain on the Western Front during the World War I, he opened the Talbot House as a rest home for wounded and shellshocked soldiers. “Siller” was an Old English name for money, being a Scottish variant of silver. The Reverend Tubby Clayton would tour with the crow’s nest using it as an attraction to raise funds for his Talbot hospice. Following the armistice, Clayton opened further Talbot Houses in London, Manchester, and Southampton.

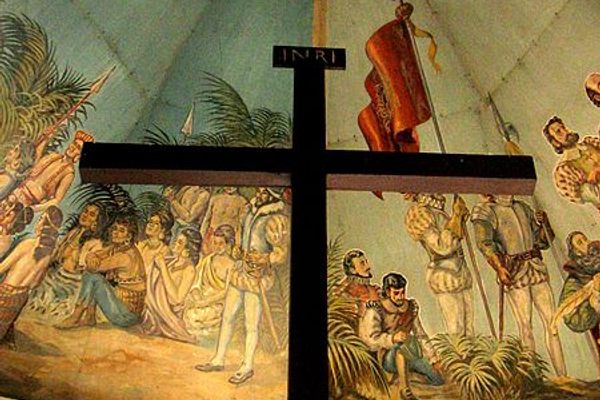

At the back of All Hallow’s church today, a narrow staircase leads the way into the crypt. The original Roman road is still here, perfectly preserved. Walking past the church register, opened to the day John Quincy Adams was married here, you take the narrow subterranean passage to a small underground chapel. The altar is made of stone, taken from Richard I’s castle Atlit, built during the crusades by the Knights Templar. And around the corner amidst such mysterious surroundings lies the crow’s nest from the Quest. Hardly known about or visited, along with the rescued cabin it is all that remains from the final voyage of Sir Ernest Shackleton.

Know Before You Go

After being removed for an exhibit in Chile in 2022, the nest has returned, and is currently situated upstairs in the main body of the church. Whether it remains there for its centenary, or will be relocated down in the crypt, is up for debate.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook