The Dissidents Cemetery

This historic Chilean cemetery is the burial place of hundreds of European and American freethinkers and non-Catholics.

On a picturesque hilltop in the colorful port town of Valparaiso, Chile, lies one of South America’s most historic and beautiful cemeteries. Yet few of its early burials are native South Americans.

Cementerio Disidentes (The Cemetery of Dissidents) is the final resting place for hundreds of European and North American Protestants, freethinkers, and other non-Catholics who died in this “skinny country,” and their descendents, who still call Chile home.

Today, we don’t tend to think of Latin America as an immigration hub. But in the 1800s, Chile, Argentina and Brazil attracted many new settlers from abroad, including quite a few whose native tongue wasn’t Spanish or Portuguese. Argentina and Chile, in fact, are mostly immigrant nations.

In Chile, it’s not at all uncommon to see place names with a familiar English or German ring. Walk around the historic Pacific seaport town of Valparaiso and you’ll find streets with names like Edwards, Cumming, Mackenna, Mackay, and even one named Calle Beethoven. Other city thoroughfares were given the Spanish names for western European countries, including Calle Dinamarca, “Denmark Street,” where you’ll find the Dissidents Cemetery.

Chilean Patagonia, at South America’s farthest tip, was heavily explored by British sailors. It too has a litany of English place names, spots like Cerro Fitzroy, Isla Wellington, the Beagle Channel, which opens into Darwin Sound. Then there’s that curious red-headed Irishman, Bernardo O’Higgins, who you can think of as Chile’s George Washington. O’Higgins was the bastard son of Ambrosio O’Higgins, a poor Irish tenant farmer from County Sligo who emigrated to the other side of the world and happened to become the Viceroy of Peru.

In the early 19th century, the Valparaiso port town was a major destination for globe-trotting mariners. The list of visitors who came by sea includes Charles Darwin, father of evolutionary biology, who docked here aboard the HMS Beagle in 1834.

British sailors and adventurers formed a major nucleus of the Chilean navy during its war of independence against Spain, and then again in the early days of the Chilean Republic. One was Lord Thomas Cochrane, who had already served with distinction in the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars. Cochrane, humiliated by a financial scandal in England at war’s end, became a Chilean citizen in 1818, then served as Vice Admiral of the Chilean Navy.

American sailors were no strangers to Valparaiso’s harbor, either. One monument at the Dissidents Cemetery honors a battle of the far-flung War of 1812, America’s “Second War of Independence.” On March 24, 1814, the frigate USS Essex, under command of Admiral David Porter, went into battle against the British vessels HMS Phoebe and HMS Cherub just offshore. Porter lost the battle and 58 American sailors died. (One sailor aboard the Essex was the future Civil War admiral David Farragut, famous for later coining the phrase, “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!” during the siege of Mobile, Alabama, in 1864.)

Valparaiso also holds a minor spot in American history and literature: Writer Herman Melville, whose seafaring days in the South Pacific took him here, opens his anti-slavery novel “Benito Cereno” off the Chilean coast.

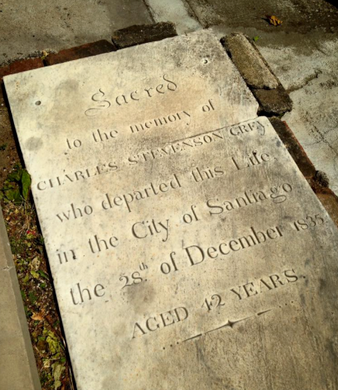

Unfortunately, until an 1883 law did away with religious discrimination in Chile’s cemeteries, if you died in Chile and weren’t Catholic, your bones couldn’t legally be buried in “holy ground.” Thus, for most of the 19th century, non-Catholics who expired even as far away as Santiago and La Serena had to be brought to Valparaiso for burial at the Protestant Cemetery, established in 1823 by British consul George Seymour. The cemetery, or “Protestant Pantheon,” popped up next to what was originally the old city jail. Before 1823, non-Catholics had been buried in the fort on Cordillera Hill or, since many of them were sailors, were simply buried at sea.

Since most of the deceased hailed originally from the British Isles, this lovely necropolis feels a bit like the old British Empire — with the added touch of South American light and Latin grace. A large number of these stones are carved in English. Poke around a bit and you’ll find the Royal Naval vault, final resting place of several dozen British sailors who died here as far as back as the 1850s, not long after Charles Darwin’s visit.

Not all the grave markers are in English, though. Many are in German and at least one is in Swedish. (One stone German cross is inscribed “Ruhe Sanft,” “Sleep tight.”)

Equally interesting are the “multilingual” stones. As different nationalities settled down in Chile, families intermarried, just like in every other immigrant nation. Surnames that came from England, Germany, Italy, Scotland or Eastern Europe began to take on a certain Spanish inflection. When women married, they added a “de” to their surnames, even if their husband’s name was, say, Scottish. One stone here memorializes a Mrs. Flora McGaw de Shaw.

Reverend David Trumbull, founder of the Presbyterian Church in Chile, was buried here, as was Henry Osborn Burdon, veteran of the Battle of Waterloo, who died in South America in 1848. An especially curious grave marker is a memorial to the city’s German-speaking fire department, the Deutsche Spritzenkompagnie.

Look around and you’ll find some of the native sons and daughters of Edinburgh, Philadelphia, Stuttgart, and London, all resting here on a sunny South American hillside. Don’t miss the monument near the entrance, written in old English lettering: “Immigrant’s Memorial Square.”

Know Before You Go

The Dissidents Cemetery is about a 15- or 20-minute walk from the popular Cerro Alegre district. Gates are open 10am - 5pm. A neighboring museum sheds some light on the town's fascinating immigrant history. Cementerio Disidentes is one of the most interesting off-the-beaten-path locations in Valparaiso. Even if you're not interested in cemeteries, it's one of the best places to get a view of this gorgeous city. Two neighboring Catholic burial grounds, including the imposing, neoclassical Cementerio Numero 2 just across the street, are a little more flowery and are also worth checking out.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook