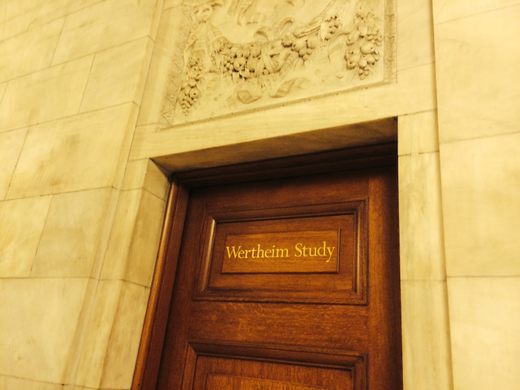

The Wertheim Study

This study room in the New York Public Library saw the creation of one of contemporary America's greatest traitors.

The main branch of the New York public library is home to many secrets, from it’s pneumatic delivery tubes to the 40 miles of shelves of underground storage hiding underneath neighboring Bryant Park. But the Manhattan icon, built in 1911 on the site of a former potter’s field and reservoir, holds a thrilling secret in one of its second floor study rooms.

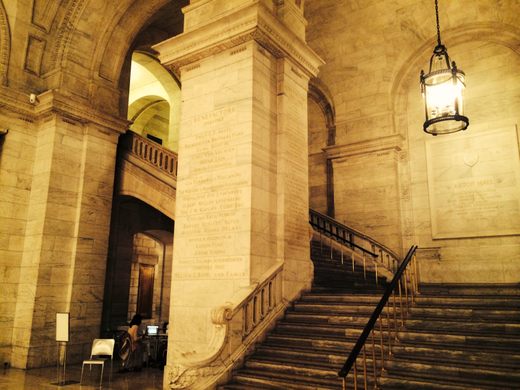

In July 1987, Earl Edwin Pitts walked up the grand steps of the public library, past the noble lion statues (Patience and Fortitude, respectively). Strolling past the security guard at the revolving doors, and across the imposing marble hallway, he climbed the steps past the Astor memorial to room 228, The Wertheim Study. It was in this room, named after Maurice Wertheim, publisher of “The Nation,” that Pitts had a fateful meeting that would begin a decade long career of espionage. What whispered words passed between the two men in that study we will never know, but then again, secrets were their stock in trade; for Pitts was an FBI agent, and the man he met, surrounded by law books, was Aleksandr Vasilyevich Karpov, an agent for the Komitet gosudarstvennoy bezopasnosti, better known as the KGB.

For the next five years, Pitts regularly met Karpov and handed over sensitive and highly classified secrets to his Soviet handler in exchange for nearly a quarter of a million dollars. Pitts had joined the FBI in 1983, and by 1987 was working in its New York bureau when he began his secret career as a Soviet spy. Amongst the high level intelligence Pitts handed over to Karpov over the next five years were reports on “recruitment operations involving Russian intelligence officers, double agent operations, operations targeting Russian intelligence officers, true identities of human assets, operations against Russian illegals, true identities of defector sources, surveillance schedules of known meet sites, internal policies, documents, and procedure concerning surveillance of Russian intelligence officers, and the identification, targeting and reporting on known and suspected KGB intelligence officers in the New York area.”

Pitts’ treason was eventually discovered in 1996 when Karpov defected to the United States, and named Pitts as a KGB operative. The FBI launched a 16-month long false flag operation during which Pitts was approached by undercover federal agents posing as fellow Russian spies. Once he was apprehended, Earl Edwin Pitts was convicted of conspiracy to commit espionage, and was sentenced to 27 years imprisonment at the Federal Correctional Institution in Ashland, Kentucky, where he remains to this day. In exchange for his cooperation, Karpov was given a new identity after he defected, and his current location is unknown.

Quite how much damage Pitts did is lost in the murky underworld of the Cold War. But affidavits of United States vs Earl Edwin Pitts are in the public record, and make fascinating reading. During his trial, the only explanation Pitts gave was to “pay the FBI back.” So the next time you are on the corner of 5th Avenue and 42nd street, pay a visit to one of Manhattan’s most venerable institutions and take a moment to remember that you are walking in the footsteps of Cold War agents, stolen secrets, and treacherous espionage.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook