AO Edited

Woodstock Opera House

This small-town opera house has appeared much more in national culture and history than its charming setting might suggest.

As far as small-town opera houses go, this one has enjoyed a pretty illustrious career. The Woodstock Opera House has appeared much more in national culture and history than its charming setting might suggest. It was the backdrop to the 1890s prison release of a famous labor leader and would-be presidential candidate, several notable actors began their showbiz careers on its stage, and in the 1990s, moviegoers watched as a curmudgeonly protagonist played by Bill Murray jumped from its bell tower.

After the Civil War, opera houses began to spring up in small towns across the United States. These buildings became fixtures in growing villages as one of the first “public” (secular) places where ordinary people could gather for meetings, celebrations, entertainment, lectures, or political activities. A local opera house was far more than just an entertainment venue—the multipurpose structures often helped establish and house small towns’ fledgling municipal services. Wherever one was built, local civic life was soon organized primarily around it. Operatic performances were rarely even part of the equation.

The town of Woodstock, Illinois, and its opera house are quintessential examples of this movement. Located 50 miles northwest of Chicago and surrounded by farmland, the area had been settled before the Civil War but really grew up after the war ended, thanks to a passenger train connecting Woodstock to Chicago. The town was incorporated in 1873, and in 1888 local officials approved the construction of an opera house on the New England-style town square. A regional architect drew up plans for a stately, three-story building with a bell tower in a Romanesque-yet-still-Victorian style. A 700-seat theater was planned for the upper stories, but the first floor was left to house city offices, the police and fire departments with their horse stables, and a small public library. Construction cost $26,000 and took about two years.

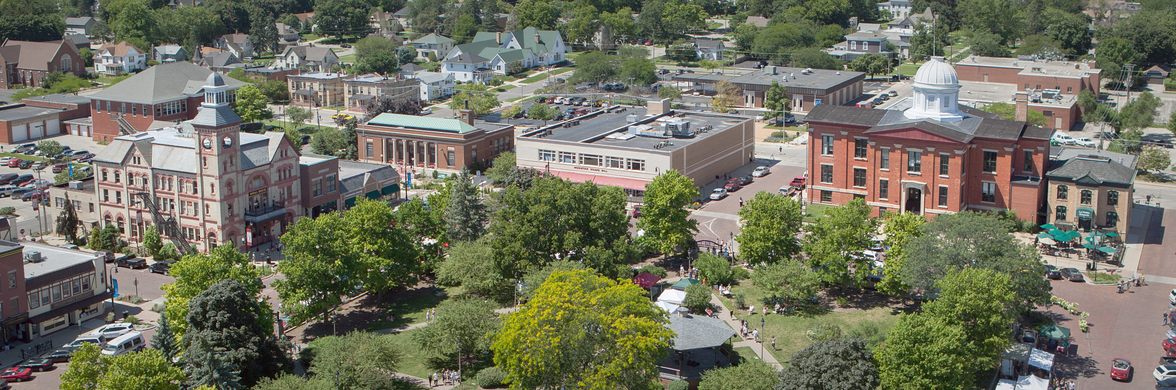

Once the opera house was completed in 1890, the community rallied around its new multipurpose building. In addition to the more traditional theatrical performances, public ceremonies, and concerts, the theater’s removable seats allowed the space to accommodate events like weddings, dances, and at least one wrestling match. The building’s ornate facade and tall tower dominated the south side of the town square, which was fast becoming a bustling center of commerce and entertainment. As the seat of McHenry County, Woodstock had also constructed the county courthouse and jail on the western side of the square a few years prior. Then as now, Woodstock’s growing downtown district was anchored by these two architectural showpieces, one with a dome and one with a tower.

In 1895, the young opera house played witness as a celebrity inmate was jailed in the neighboring courthouse. That year Chicago officials chose Woodstock as a convenient but remote enough location to hold Eugene V. Debs, a nationally-known labor activist. Debs was the founder and former president of the American Railway Union, which organized workers of a prominent railcar manufacturer, the Pullman Company of Chicago. The union fought Pullman’s pay cuts in 1894 with strikes but they were unsuccessful. Undeterred, Debs and the ARU tried organizing a nationwide boycott of all trains operating Pullman cars.

President Grover Cleveland called on the military to keep the nation’s train travel up and running, causing riots (some deadly) to break out nationwide until the movement collapsed. Debs was subsequently arrested, but officials were reluctant to jail him in Chicago where he was still surrounded by supporters. So Debs served out his six-month sentence in Woodstock’s jail instead, reading Karl Marx for the first time in plain sight of the opera house. On the day of his release, the square and surrounding streets filled with thousands of onlookers angling for a peek. Debs had become a socialist and a famous one at that. Starting in 1900, he would run (unsuccessfully) for President in five straight elections.

Not long after Debs’ last presidential gambit, a unique boarding school in Woodstock accepted a pupil named Orson Welles. In 1926 at the age of 11, Welles followed in the footsteps of his much older brother and enrolled at the Todd Seminary for Boys less than a mile north of the Woodstock Opera House. He spent five formative years there, where the pragmatic curriculum of headmaster Roger Hill allowed him to focus on his passion for writing, stagecraft, and acting. Hill became something of a father figure, mentor, and close personal friend to Welles. After graduation and some time abroad, Welles returned to Todd in 1934 and formally launched his career in show business by presenting a summer of Shakespeare shows from the opera house stage. (The young Welles’ performances were so good that Hill allegedly convinced the New York Times to review them.)

In 2013, the opera house dedicated the stage in his honor, a tribute to Welles and his groundbreaking success across American entertainment. For his part Welles paid a small tribute to Woodstock later in life too, referring to it in interviews as the place he most thought of as home.

Plenty of other national talent has graced the stage of the Woodstock Opera House. Paul Newman got his start in a 1940s local summer theatre troupe along with Geraldine Page. To this day, high-profile musical acts or comics occasionally pass through. In recent memory, songwriter Jimmy Webb and comedian Caroline Rhea have performed, and actor/musician Jeff Daniels played a show with his son’s band. Daniels said he considered playing the Woodstock Opera House to be “Broadway opening night for me musically.”

If this century of history was unknown to you but the building itself still looks somehow familiar, you’re not alone. The Opera House’s largest entry in the zeitgeist is more recent still: you may recognize it from the 1993 movie Groundhog Day. Though the story takes place in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, the movie was filmed entirely in Woodstock. The opera house is subtly disguised as the Pennsylvanian Hotel, where contemptuous news anchor Phil (Bill Murray) and his producer Rita (Andie MacDowell) stay at the start of a reporting trip about Groundhog Day celebrations in the Square. Hijinks ensue, and in a later scene, Murray’s character takes a tumble off the building’s bell tower. (He survives, in a way.)

Now over 130 years old, the Woodstock Opera House continues its starring role as a smalltown landmark and anchor of the downtown business district. As anywhere, town centers experience ebbs and flows, but the opera house has been a constant through them all, a sort of tall brick ambassador with special connections to every era of 20th-century American life. That heritage was recognized already in 1974 when it was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, and it continues to this day. Each passing season adds news layers of history: local theatre productions, annual Christmas Tree exhibits or crowded city council meetings inside, and summer concerts, farmers market, or annual Groundhog Day celebrations outside.

Opera houses like this are not necessarily still bustling centers of town life like they once were, but in many ways, Woodstock is on the cutting edge of communities trying to preserve and reshape their historic downtowns for the 21st century. And in this case, that will always center around its opera house, a leading lady of history and culture.

Know Before You Go

Woodstock is about 90 minutes from downtown Chicago by driving or Metra train. Street parking is readily available in and around the Opera House in the downtown district. For box office, contact information and opening hours, visit the official website.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook