A Hot Take on the Steamy History of the Jacuzzi

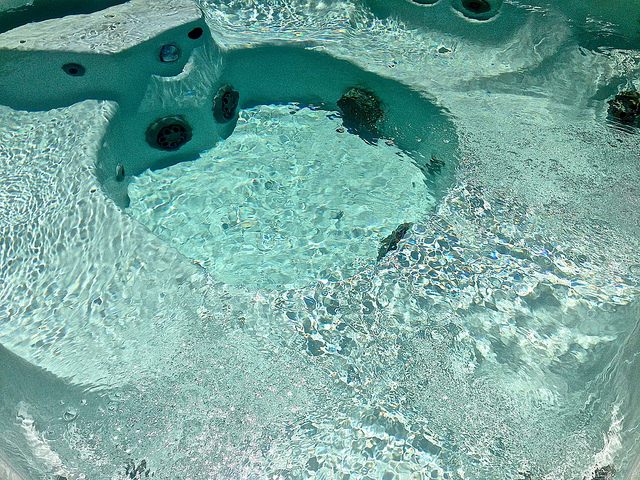

(Photo: Rainer Plendl/shutterstock.com)

(Photo: Rainer Plendl/shutterstock.com)

The L-shaped building on the corner of San Pablo Avenue and Page Street in Berkeley is currently occupied by Fenton MacLaren, a home furnishing store run by two brothers. (“Fenton MacLaren” comes from the middle names of Scott and Ken Parker.) They’ve been a successful family business for over 30 years, which is a long stretch, particularly for a city in the midst of a gentrification changeover. But it’s nothing compared to the site’s previous tenants, another band of entrepreneurial brothers.

This location is the site of the old Jacuzzi Brothers machine shop, home to an ever-expanding family of Italian immigrants who experienced triumph, tragedy, fame, great wealth, and then poverty. The Jacuzzi’s influence on American culture is hard to overstate, though: Few can claim to infiltrate the national vernacular in such a profound and memorable way. Before there was Netflix-and-chill, there was a large tub filled with steamy bubbles, and room for two.

(Photo: Grant Guarino/flickr)

(Photo: Grant Guarino/flickr)

Like Kleenex and Vaseline, Jacuzzi has transcended a brand name and come to signify the entire line of products. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, a “jacuzzi” is “used for a bathtub in which a pump causes water and air bubbles to move around your body.” But before there was a whirlpool, there was a family.

Their story begins with Giovanni and Teresa Jacuzzi, born in 1855 and 1865 respectively, in the small Northern Italian village of Casarsa della Delizia, 50 miles north of the Adriatic Sea, roughly midway between Trieste and Venice. The two were married in 1886 and, quickly, started work on spawning the next generation. (Their eldest son Rachele came first, later to be accompanied by 12 brothers and sisters.) But despite living in a picturesque hamlet in the Italian countryside, Giovanni was not happy with the county’s political climate.

“My grandfather was anti-war,” says Ken Jacuzzi, now 74 years old, in a phone interview. “He didn’t want to lose any children in the war.”

Giovanni sent the family’s males to Germany to find work. Some became bricklayers, while Rachele worked as a telegraph operator. But with the assassination of Archduke Francis Ferdinand and his wife Sophie on June 28th, 1914, the world’s tenor shifted. Europe was becoming a war zone.

And so, with his sons the age where they could be conscripted into the army, Giovanni ordered them to leave the country and head to America. They left, sometimes several together, sometimes alone, the early immigrants making a pit stop in Los Angeles before winding up in the Bay Area. With 13 total children to make the journey, the process was slow, but the American-residing wing of the family kept busy.

Candido, Gelindo, Frank, Joseph and Valeriano Jacuzzi. (Photo: Courtesy Ken Jacuzzi)

Candido, Gelindo, Frank, Joseph and Valeriano Jacuzzi. (Photo: Courtesy Ken Jacuzzi)

Rachele, the oldest, was the great inventor. After getting his feet wet in the garage of James Smith McDonnell—who’d go on to co-found the massive aerospace corporation McDonnell Douglas—he did mechanic work near the flying field of the 1915 Panama-Pacific World’s Fair in San Francisco. While watching the planes at the exhibition, he believed he could design a better propeller. And so he did: The Jacuzzi Toothpick Propeller.

The popularity of the design, along with the burgeoning avionics industry, was the family’s first real success. Everyone from the U.S. Air Force to Charles Lindbergh utilized the design. The resolution of WWI was a mixed bag for the family: It heralded the completion of the family exodus to the U.S. (including the youngest son, Candido; more on him in a moment), and the end of the military contracts. Needing work, the family tried their hand in the airplane business.

“Rachele wanted to fly,” says Kenneth. “That was his dream.”

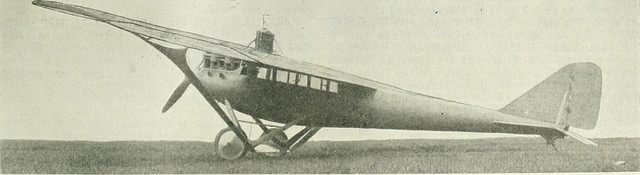

The seven brothers, now based in Berkeley, spent their time designing and building the Jacuzzi J-7, the first airplane ever designed with an enclosed cabin. But before the big contacts were signed, the brothers had to prove the plane’s worth. To show it off, they flew it across the Bay. They flew it through a heavy storm. It landed safely, without damage. The design seemed solid. So, when they heard about a new contract from the U.S. Mail to deliver letters by air, they put their hat in the ring.

On April 16th, 1921, the J-7 made the then-treacherous flight from San Francisco to Reno, Nevada. Everything went smoothly, the U.S. Mail were ready to sign a deal, but they wanted to check just one more thing before committing.

A Jacuzzi monoplane, 1921. (Photo: Internet Archive Book Images/flickr)

A Jacuzzi monoplane, 1921. (Photo: Internet Archive Book Images/flickr)

To see if the plane could transport tourists from San Francisco to Yosemite National Park, a crew of four men, including 26-year-old Giocondo Jacuzzi, took a test flight. The journey to Yosemite went smoothly, with the quartet landing in a patch of grass near the famed rock formation known as El Capitan. After two nights in the park, they headed back home, with a 6 a.m. departure time. Two-and-a-half hours later, they started a descent into Modesto, a small city about 90 miles east of San Francisco. The rationale for this side trip remains a mystery. Some sources say that it was a stop dictated by pilot “Bud” Coffee who wanted to see his girlfriend. Others suggest that it was a mistimed acrobatic maneuver that caused the plane to start going down. In any case, something went wrong. The left wing snapped off, followed by the right, sending the plane into a tailspin. All four passengers died, including Giocondo.

“My grandfather said ‘absolutely no more flying’,” said Ken. “He didn’t want to lose any more sons.”

And so ended the family’s aviation dreams. “They were essentially broke. The company started from scratch again,” says Ken. The family took odd-jobs to get by. They developed and tweaked machine designs, creating a variety of fans, furnaces, and different wind machines that kept frost off fruit orchards.

Rachele, meanwhile, continued tinkering, using what he learned in aviation design, but in a different context. In 1925, Rachele developed a pump to move water with water. As Ken writes in his book Jacuzzi: A Father’s Invention to Ease a Son’s Pain, “The principle was simple: water would be forced down a pipe, creating a vacuum and bringing water up.” The Bay Area’s proximity to the San Joaquin Valley, which was booming as a farming region, led to a nearby market to hawk this irrigation-assisting technology.

The sociable Candido was the frontman, selling the family’s products door-to-door. But the role was not without its headaches. “He got the door slammed in his face because he didn’t speak English,” remembers Ken. To counter the prejudice, Candido went to night school to improve his English, remaining careful to check mailbox names before knocking. If he saw a Latin name, he’d make the entrance. “They probably don’t speak English better than I do, he thought,” says Ken. As his English improved, he expanded his range. And with the success of the water pump, the family was, after the conclusion of World War II, able to buy a factory in Richmond, CA.

In 1937, tragedy struck the family again. On August 24th, Rachele, now 50 years old, died of a massive heart attack. His brother Giuseppe took the family business over briefly, before the youngest son, Candido, rose in the ranks. The torch was passed, the transition was complete. The family was about to begin dominance of another realm.

Ken Jacuzzi with his family, c. 1946. (Photo: Courtesy Ken Jacuzzi)

Ken Jacuzzi with his family, c. 1946. (Photo: Courtesy Ken Jacuzzi)

On April 22nd, 1941, Candido and his wife Inez welcomed their fourth child, Ken. He was a healthy kid—he walked and ran before he was nine months old. But before his second birthday, Ken contracted strep throat.

While this seems eminently treatable now, Ken’s illness occurred in the era before antibiotics. Strep leads to rheumatic fever, which leads to Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis (JRA), a syndrome that causes persistent joint pain, swelling, and stiffness. In Ken’s case, the infection went systemic, meaning his entire body was affected. The family took him to a rheumatologist, who recommended physical therapy in addition to a constant and steady assortment of drugs. He also recommended a more advanced treatment.

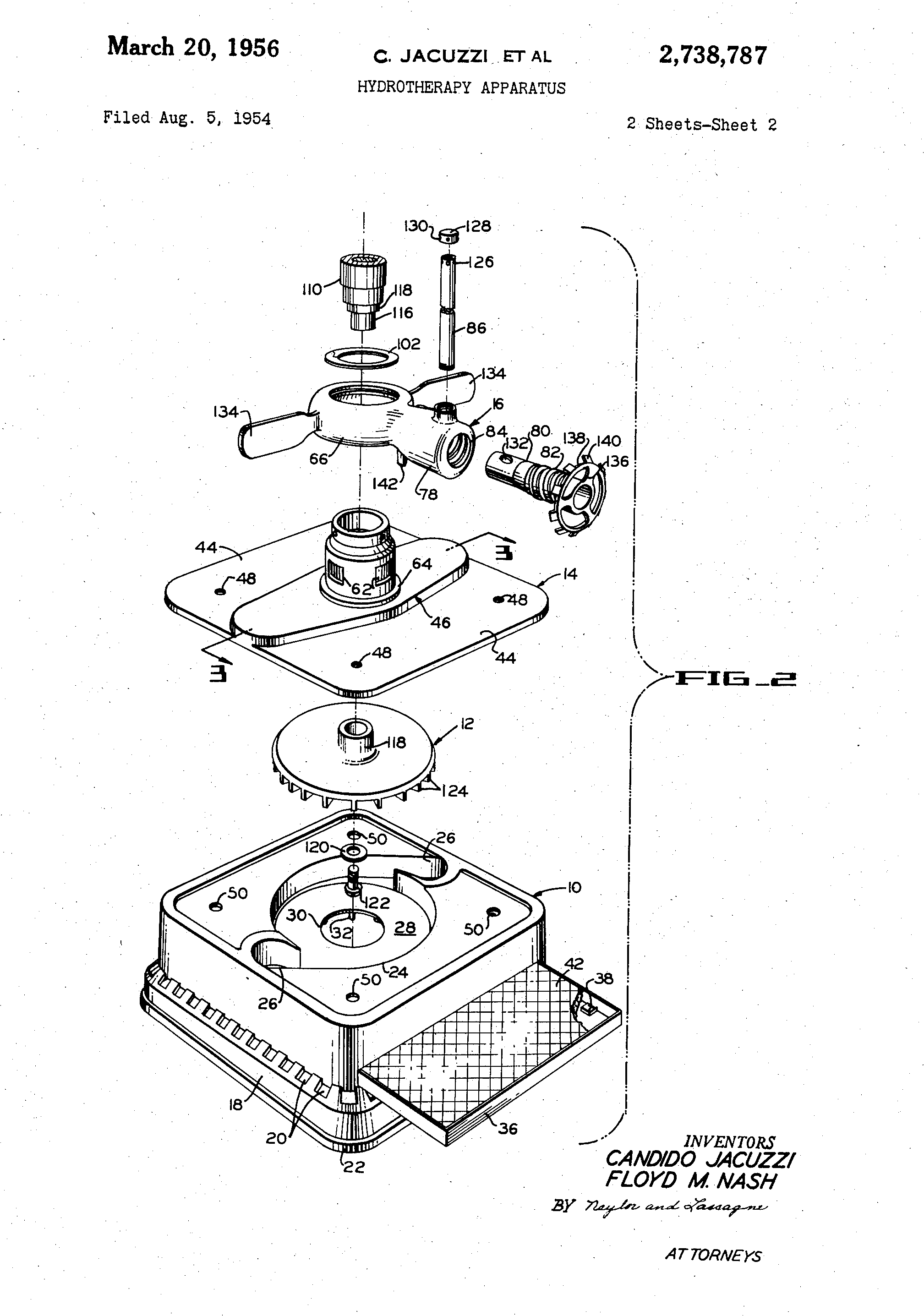

“Hydrotherapy,” says Ken, “to warm up my body and joints, to get them more flexible.” Inez noticed Ken reacted well to the water-based treatments, but couldn’t always make the drive. So, to cut down on he logistical hassle, she enlisted Candido to take a look at the hydrotherapy unit. “He came to the conclusion that it’s just pumps. So, he developed a design.”

Candido developed what would become the model J-300 pump. He took the whirlpool design back to the doctor, who suggested others could benefit from home hydrotherapy. Candido saw an opportunity to bring the Jacuzzi Whirlpool Bath to the home market, but first he had to get it past his brothers and sisters.

“He had some big resistance,” said Ken. “The family was afraid to get into the consumer market and become competitors to General Electric. They didn’t know a damn thing about consumer products.” If GE decided to make and sell their own version, adding to their own large line of appliances, they’d blow the family’s small start-up right out of the water. But after months of pleading, Candido convinced the family. “They didn’t always agree with him, but they respected him,” says Ken.

A 1954 patent for a Jacuzzi hydrotherapy apparatus. (Photo: Google Patents US2738787)

Before it could compete, though, Candido needed to get the word out. With the help of an L.A. based freelance sportswriter Ray Schwartz, the Jacuzzis got their product on Queen for a Day, a daytime TV show broadcast from 1956 to 1964, first on NBC, and then ABC. The concept was simple: host Jack Bailey would ask the female contestants about their hard luck story and then, using an applause meter, rule on the most heart-breaking. The winning contestant was named “Queen for a Day” and given a variety of prizes, depending on their specific plight. “Every time a queen had a story that had some medical-related aspect to it, one of the prizes was a jacuzzi,” said Ken. “The name ‘Jacuzzi’ became known overnight.” And since this was a nationally-syndicated program in a non-fractured media era, a TV show like this could reach 20 million people during a single show. This was a big deal, and sales followed suit.

“It was just a phenomenon,” says Ken.

And the product wasn’t just for unfortunate housewives anymore. With testimonials from celebrities like Jayne Mansfield, the Jacuzzi Whirlpool Bath become a symbol of luxurious living. The company expanded to other counties around the world, including Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Chile, and back to the family roots in Italy. In 1968, along with his grandnephew Roy, Candido tweaked the original design to create the first self-contained whirlpool bath. In 1970, they developed the first two-person whirlpool. (In all, the family holds more than 50 patents.)

A 1987 advertisement for Jacuzzi. (Photo: ebay)

A 1987 advertisement for Jacuzzi. (Photo: ebay)

Ironically, while the world soaked in these romantic (and weirdly sexualized tubs), the Jacuzzi family themselves refrained from opulence. There are no reports of Jacuzzis hanging out at the Playboy Mansion. “My father was a very loving man,” says Ken. “One thing he wanted to do, above all else, was keep the family together and provide work for everyone who wanted it.”

By the late 70s, the business had grown unwieldy—Giovanni’s grandchildren now numbering over 100—and the family decided to take the company public. But time was not on their side. “It was the first Arab oil embargo, so the price of gas shot up,” said Ken. They ended up selling to Walter Kidde & Company for $70 million, and have since been through a number of business transactions and machinations. The brand name is mostly not associated with the original family.

In 1986, Candido died at the age of 83 years old. He had since moved to Scottsdale, Arizona, where Ken still lives. But while his name is known the world over for luxury, the wheelchair-bound Ken lives an existence far from the rap videos and Bond movies where the jacuzzi thrives.

“I’m not independently wealthy. I have a mortgage, and credit card debt, the whole nine yards,” he said. “But I’ve lived an amazingly rich life and have been blessed with a loving, caring wife. It’s been a damn good life.”

Update, 10/6: An earlier version of this story misstated the relationship between Roy and Candido Jacuzzi: Roy is his grandnephew. Also, the Jacuzzis did go broke but they never actually declared bankruptcy.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook