The 1980s Media Panic Over Dungeons & Dragons

From Mazes and Monsters to Dark Dungeons, D&D was a lot scarier in the 1980s.

The 1980s were the best of times and the worst of times for Dungeons & Dragons (Eric Grundhauser)

These days your life isn’t complete if you aren’t part of a role-playing gaming group, but it wasn’t that long ago that playing Dungeons & Dragons was seen as a surefire ticket to madness and damnation.

During the 1980s, D&D became associated with violence and teen suicide, casting a spell over the media that resulted in some strident anti-fantasy propaganda.

Dungeons & Dragons, for all of you level one barbarians out there, is a tabletop role-playing game created by Gary Gygax, and first published in 1974 by Tactical Studies Rules, Inc. (TSR). Taking place in a world of high fantasy, it involves players assuming the roles of fictional characters and talking their way through quests, with the help of the god-like Dungeon Master. Originally there was no board or figures, just sheets of character statistics, dense rulebooks, and handfuls of dice to determine your fate. Oh, and the imaginations of the players and Dungeon Master.

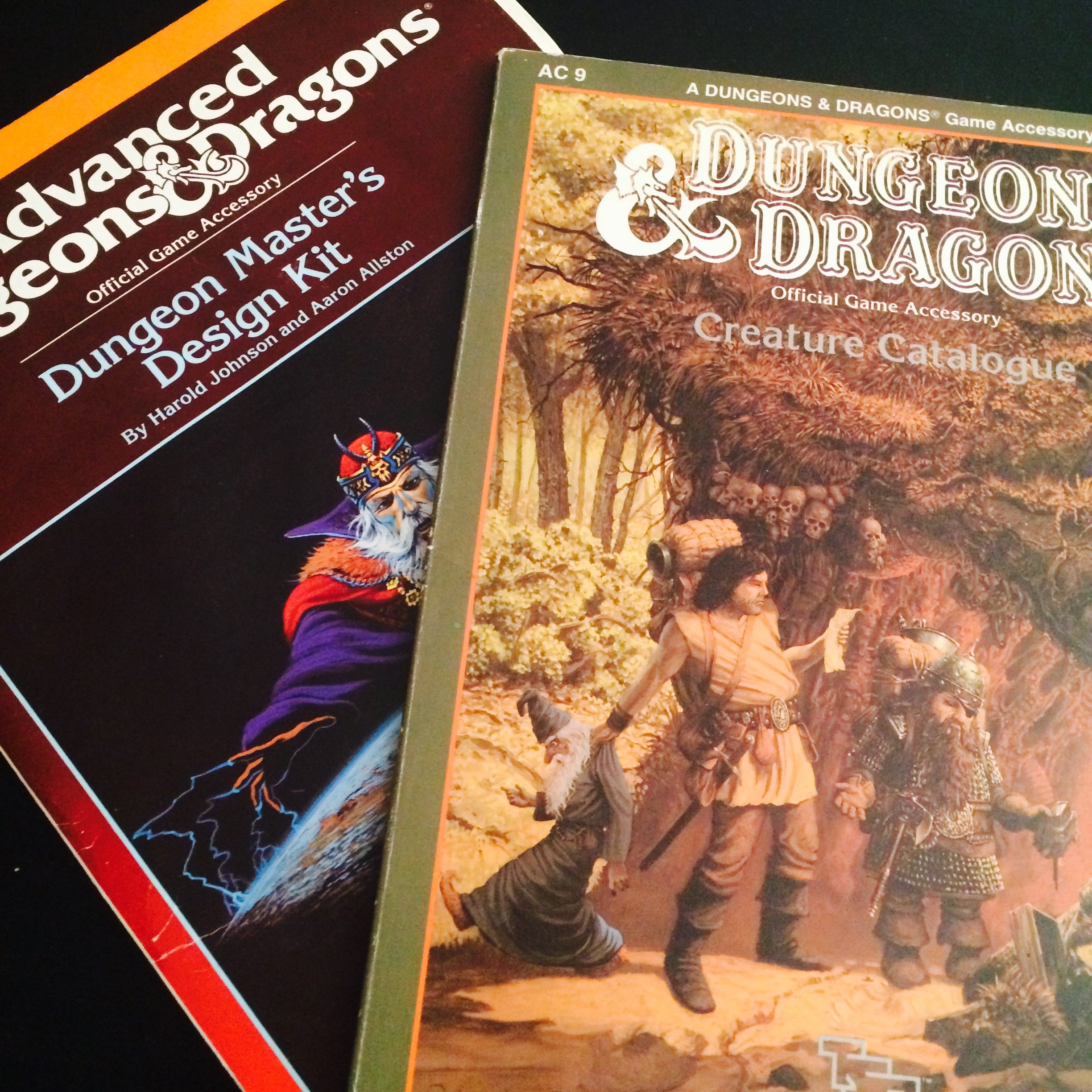

The tools of the devil? (Scott Swigart/CC BY 2.0)

The game became an instant hit among mid-70s “indoor kids,” who were looking for a fun way to exercise their imaginations and play around in a vast, complex world of magic and mystery. Unfortunately, that same desire for escape often goes hand-in-hand with depression and other feelings of isolation.

The catalyzing event that started the moral panic over D&D was the disappearance of James Dallas Egbert III in 1979. Egbert was a gifted computer programmer studying at Michigan State University, having been accepted at the age of 16. While at the school, he was involved with a D&D group that would sometimes do a little LARPing in the privacy of the university’s underground steam tunnels. Egbert disappeared into the steam tunnels in August of 1979, with the intention of committing suicide by overdosing on quaaludes.

Egbert’s family hired enterprising private detective William Dear to find their son. During his search, Dear learned of Egbert’s D&D hobby, and made it the focus of his investigation. Egbert’s disappearance came to be blamed on a “Dungeons and Dragons game gone awry.” Dear concluded the game had driven him mad, that he lost the ability to discern reality from fiction and had gone off on some insane, delusional quest. Of course when the media got wind of this, it planted the seeds of D&D as a corruptor of youth, and maybe even worse.

The truth was much more tragic. Egbert hadn’t rolled so well in his suicide attempt in the steam tunnels, and had survived. He fled into hiding, staying with friends before finally giving himself up to Dear in September of 1979. As it would turn out, Egbert’s participation in D&D games was not the reason for his disappearance. He had struggled with drugs and depression, which were the true culprits behind his suicide attempt. Tragically, another attempt the following year ended in his death. But even with the truth of the case settled, Dungeons & Dragons had acquired a bad reputation.

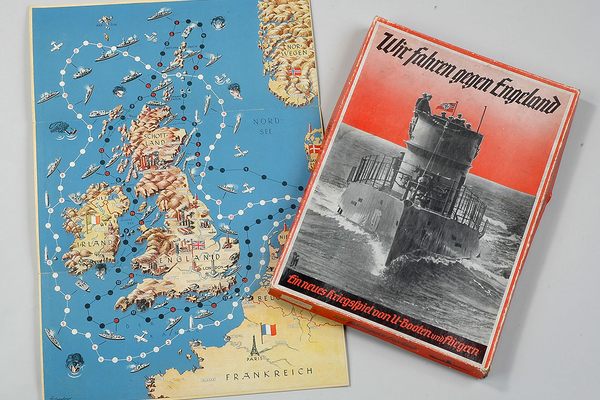

Roll for TV movie. (Youtube)

Dear sensationalized the Egbert case in his 1984 true crime book The Dungeon Master: The Disappearance of James Dallas Egbert III, but before even he could get there, novelist Rona Jaffe churned out the moral panic classic, Mazes and Monsters. Capitalizing on the public fear of D&D evoked by Egbert’s case, the plot of Jaffe’s novel revolved around a gaming group in which one of the players goes off the deep end, and begins hallucinating that the fantasy world is real, both scaring his friends and eventually attempting suicide.

Jaffe’s lack of understanding of the game and its players made for a laughably arch narrative that had little to do with D&D or psychosis. For instance, take this passage on page 51, wherein a character decides to sleep in a cave and dreams of his fantasy:

And meanwhile, somehow it seemed as if sleeping here gave him proprietorship, making the caverns his own. He slept, and dreamed of the game, dreamed that they all loved him. A whole tribe of Sprites was sitting on little stone mushrooms, all applauding for him. You are the cleverest of all, O Freelik the Frenetic of Glossamir! they cried admiringly in their tiny voices. They were wearing silken robes in pale, iridescent colors, and every one of them looked just like him.

Despite reams of purple prose, the novel successfully captured the fear of fantasy role-playing that had infested the culture. By 1982, CBS had produced a low budget TV movie based on Mazes and Monsters featuring a young Tom Hanks as the teen who loses himself in the game.

Mazes and Monsters wasn’t the only book to capitalize on the trend. Hobgoblin by John Coyne, was also published in 1981, with a similar premise. Although this book too chronicled a gamer’s descent into madness, Coyne’s novel painted the scenario like a horror story.

By 1984, fantasy roleplaying had evolved from thretening the innocent minds of America’s youth to threatening their eternal salvation. Religious mini-comic author Jack Chick published one of his “Chick Tracts”—those extreme religious comic book pamphlets you find on the bus—about the issue, tying fantasy roleplaying directly to the occult. Called Dark Dungeons, the thin pamphlet tells the story of Debbie, a young woman who gets seduced by a witchy dungeon master who teaches her to embrace evil through the game.

Through the course of the story, Debbie uses a “mind bondage” spell on her father to get spending money and finds the body of a friend who committed suicide after losing her game character. Eventually Debbie seeks the help of an ex-witchcraft practitioner (a Fundamentalist Christian), who casts the demons from her and invites her to a book burning. Dungeons and Dragons had always featured demons, angels, and other monsters with biblical ties, but these in-game creatures were now being seen as conduits to the “real” thing. Some had even come to believe that the gamebooks contained actual spells and curses that kids were taking part in.

Like Mazes and Monsters, Dark Dungeons was adapted into a short film, but not until 2014.

The fear of fantasy roleplaying was truly legitimized in a 1985 60 Minutes broadcast in which Ed Bradley took an arguably biased look at whether or not Dungeons & Dragons was as harmful as many thought. The highlights of the story are interviews both with D&D creator Gygax, as well as the Pulling family, who in 1982 had started an anti-occult group called Bothered About Dungeons and Dragons (BADD), after their son killed himself.

The Pullings came to believe that their son had been placed under some sort of death curse while playing D&D at school the day he died. Bradley gives some voice to a group of players as well as Gygax and TSR’s PR agent, but most of the piece is spent on the Pullings and investigation of crimes said to involve D&D. At one point, Bradley even asks Gygax why he doesn’t add a warning to the game letting people know of the potential harmful effects it might have on players, tacitly confirming the fears fantasy role-playing’s opponents had been creating.

The controversy surrounding Dungeons & Dragons continued throughout the 1980s. When the second edition of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons was released in 1989, TSR removed all mention of demons and devils, and skewed gameplay to more heroic actions as opposed to the more ambiguous tenor of the first edition. As the 1990s moved on, attention moved away from the evils of pen-and-paper roleplaying games, and focused on violent video games or other cultural boogeymen.

D&D eventually got its devils back, and enough room from its 1980s image to publish such great sourcebooks as The Book of Vile Darkness. However, in those circles where reference to Harry Potter and talk of fantasy violence is still seen as a ticket to the dark side, D&D is still the bad boy of roleplaying.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook