The Creative and Forgotten Fire Escape Designs of the 1800s

Some were more logical than others.

In the morning of March 10, 1860, a crowd of several hundred New Yorkers looked up curiously at a long cloth chute dangling from the top of City Hall. The tube was supported by ropes along its sides, with one end fastened to the top of the building and the other held by people on the ground. “Through this bottomless bag the persons in danger are expected to slide,” reported Scientific American in its March 10 issue.

A group of adventurous boys and men slid daringly through the chute, the spectators both relieved and amused when they reached the ground in one piece.

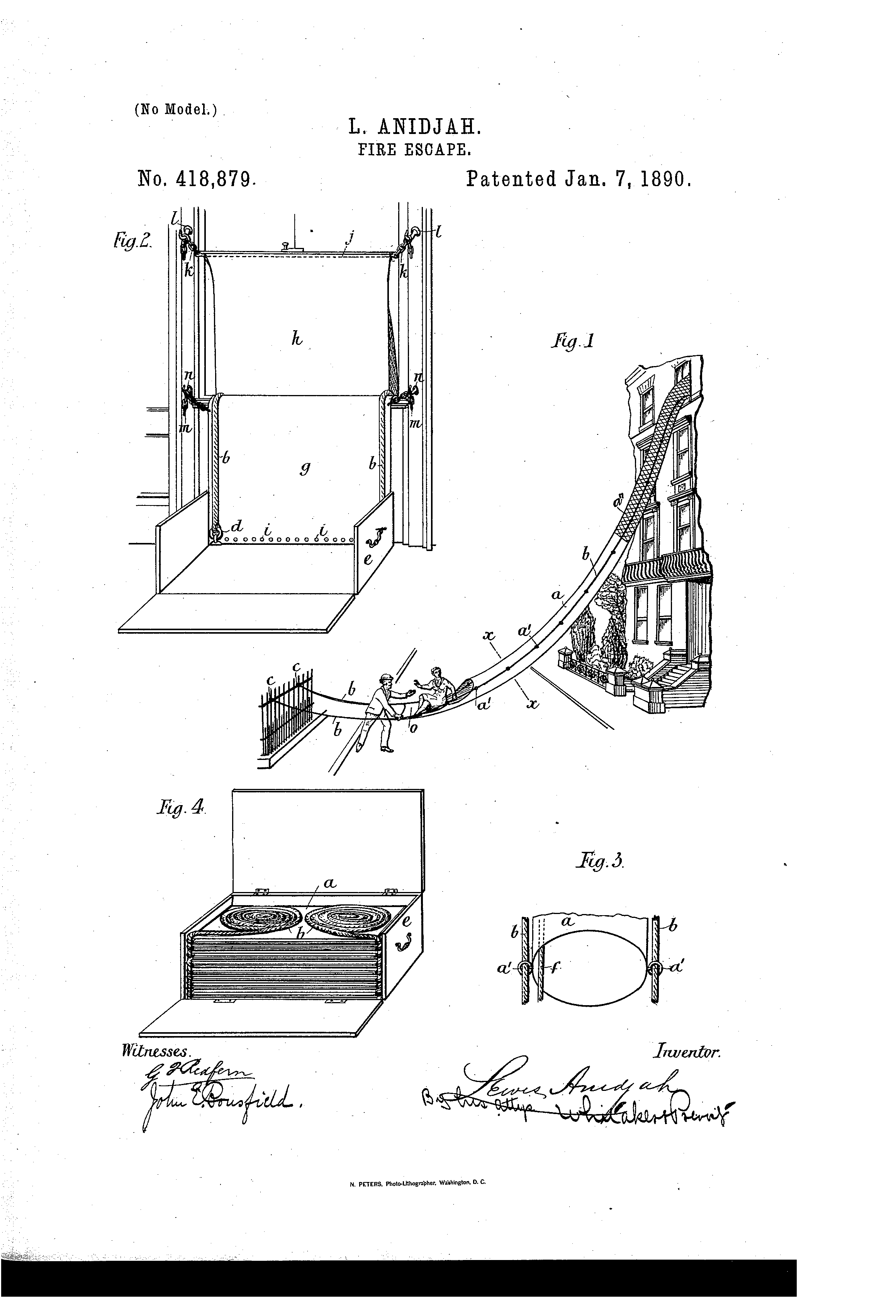

Inventor W.W. Van Loan’s English-made cloth tube, experimentally demonstrated at City Hall, was just one of the many kinds of fire escape contraptions of the 1800s and early 1900s. New household technologies such as oil and gas lamps and kitchen ranges had become commonplace, and also a common cause of fires. Consequentially, inventors came up with creative mechanisms to help escape from a burning building.

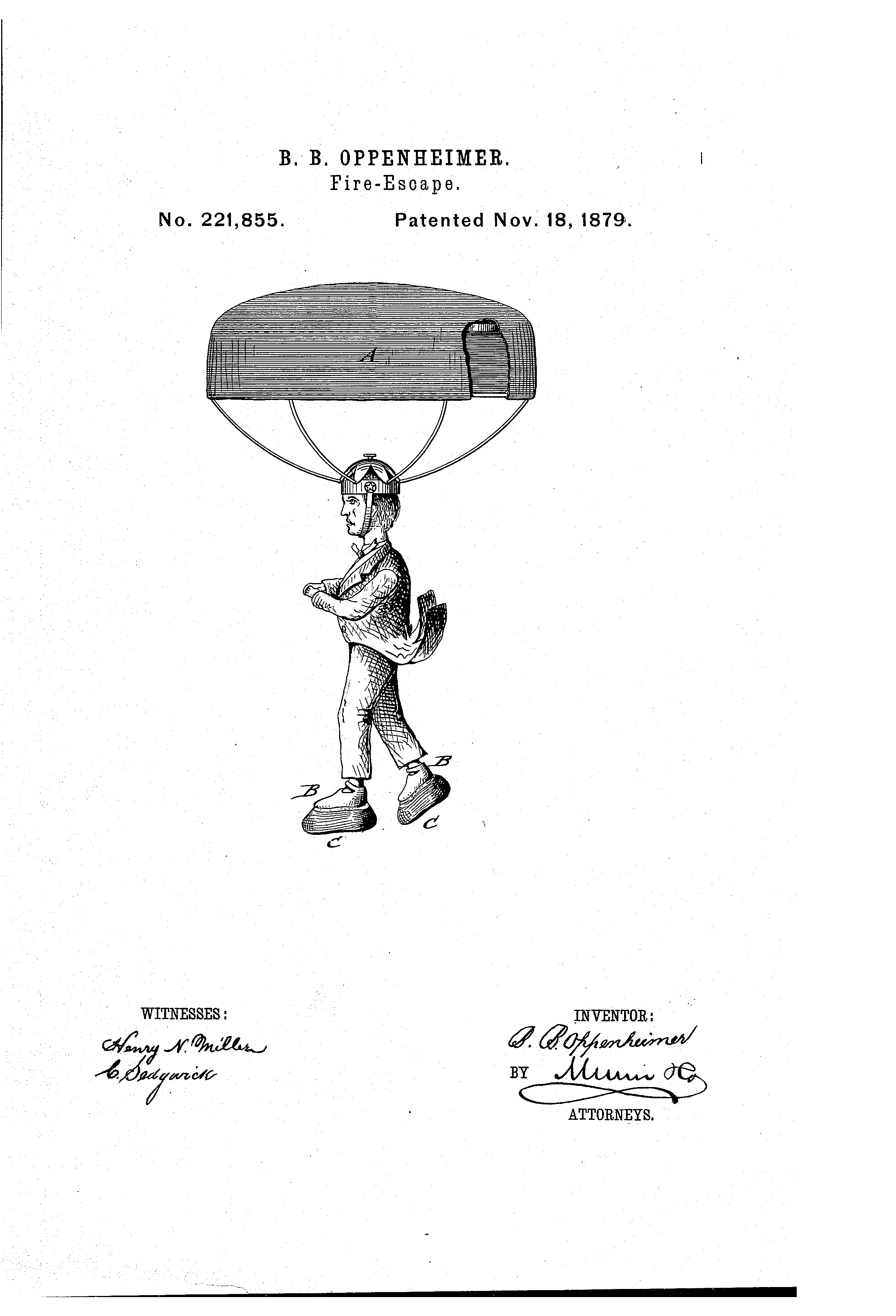

While most patents were portable variations on ropes, chutes, and ladders-on-wheels, parachute helmets and winged apparatuses leaned more towards the bizarre and ridiculous.

“There are a lot of designs for fire escapes, but none of them really inspire confidence,” says National Archives archivist Julie Halls, who authored a section about fire escape patents in her book Inventions That Didn’t Change the World. ”There’s a flimsy looking contraption designed to catch you if you jump out of a window, and various baskets attached to ropes and pulleys that are meant to lower to the ground. Although none of them look very practical, they do reflect the fear of fire at that time.”

By the 19th century, fire risks began to increase at an alarming rate within homes and factories. Faulty home appliances like kitchen ranges and small bathroom boilers (also called geysers) were prone to explode, wrote Halls in Inventions That Didn’t Change the World. Oil and gas lamps, stoves, hearths, and chimneys were all sources of inferno.

Unfortunately, Victorian popular fashion did not mix well with these sources of heat. The brush of a six-foot wide crinoline dress against a hearth or stove would engulf the material (and the woman in it) in flames. Many tragic deaths were caused by scorched crinoline. Other women donning the same style could only watch in horror, knowing if they got too close to assist they too could end up caught in an inferno, Halls wrote.

The fireplace was a symbol of Victorian domestic life, and firemen became heroic figures in the public imagination. It was common for fires to attract large crowds of spectators, the head of the Metropolitan Fire Brigade in 1865 even playing up the public performance aspect of fire fighting, Halls says.

With the higher number of conflagrations and casualties, came a greater number of fire escape inventions, particularly those aimed at middle-class consumers, says Halls.

“Patents for fire escapes increased from just a handful before 1860 to dozens each year in the 1860s,” Sara Wermiel wrote in Technology and Culture. In New York, lawmakers did not specify the kinds of devices that would qualify as safe and approved fire escapes. The lack of specificity and the sheer demand “inspired inventors to turn out a range of mainly impractical things they dubbed ‘fire escapes,’” she wrote.

Many didn’t see the need to construct additional exits and stairs within buildings since most were small, and required only a rescue ladder. From 1862 to the end of the decade, New York City’s building officials accepted portable devices, including such inventions meant to be worn by an escapee as he or she jumps from the window of a tall building.

B.B. Oppenheimer’s 1879 patent for a fire escape helmet would have included a wax cloth chute, about four to five feet in diameter, attached in “a suitable manner” to the head. “A person may safely jump out of the window of a burning building from any height and land without injury and without the least damage on the ground,” Oppenheimer wrote. To soften the impact, his invention also featured overshoes with thick elastic bottom pads.

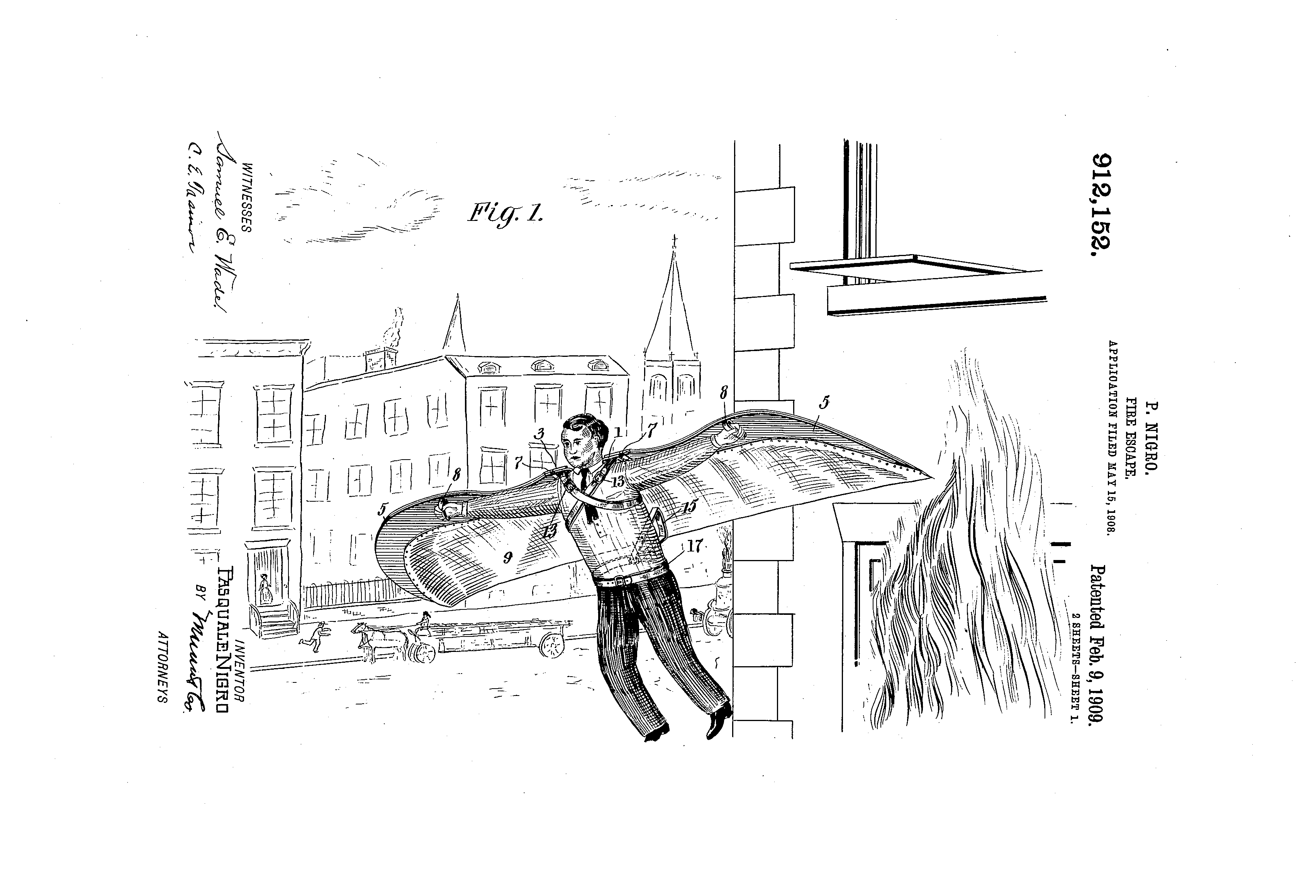

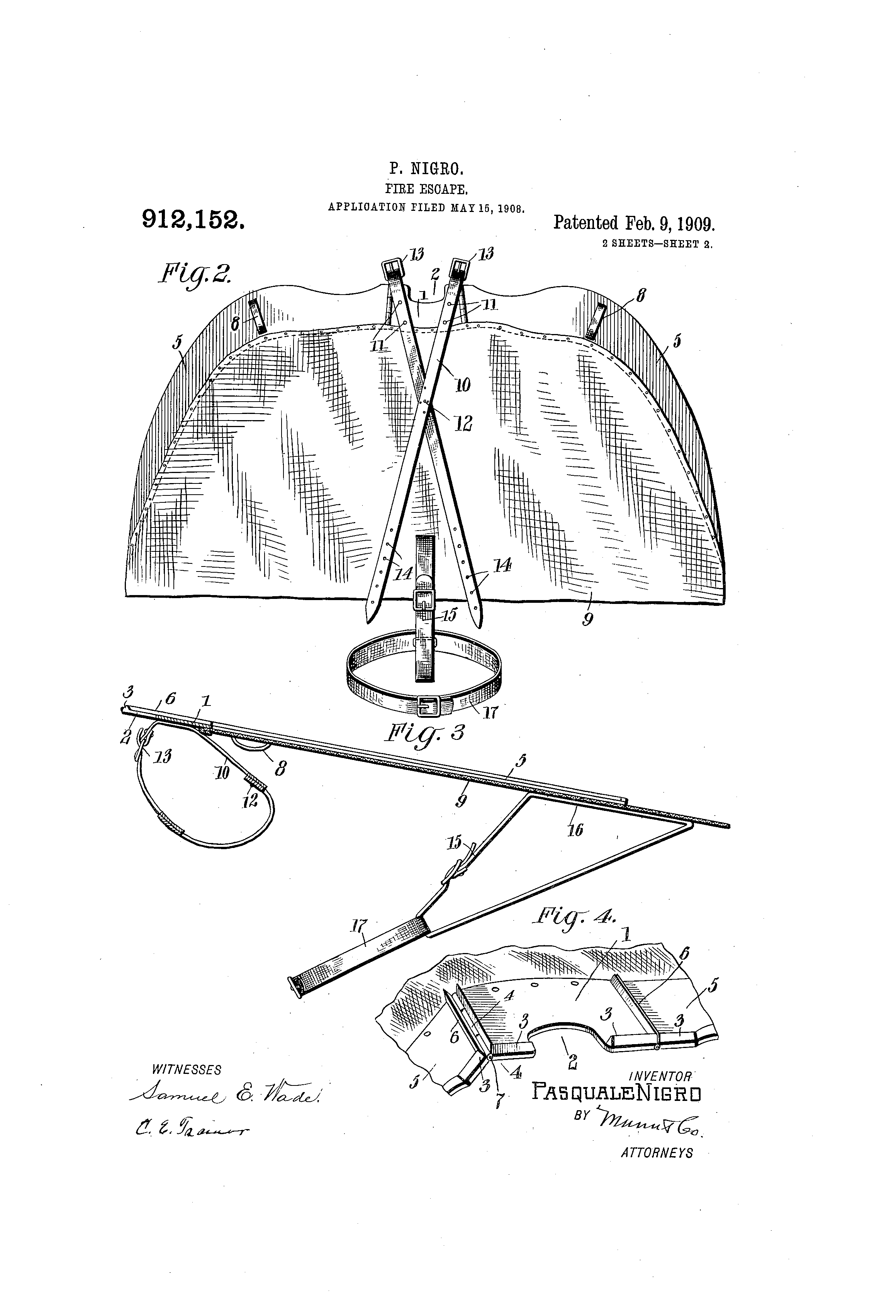

In a similar vein, Pasquale Nigro proposed a fabric-covered set of wings that would allow a wearer to fly down to safety. He wrote: “In operation, the wearer engages the loops with his hands and is prepared to leap, the air imprisoned beneath the fabric material, serving to up-hold the wearer and break the force of his fall.”

Nigro asked for about $33,000 in 1909 to execute his invention, however, the idea never quite took off.

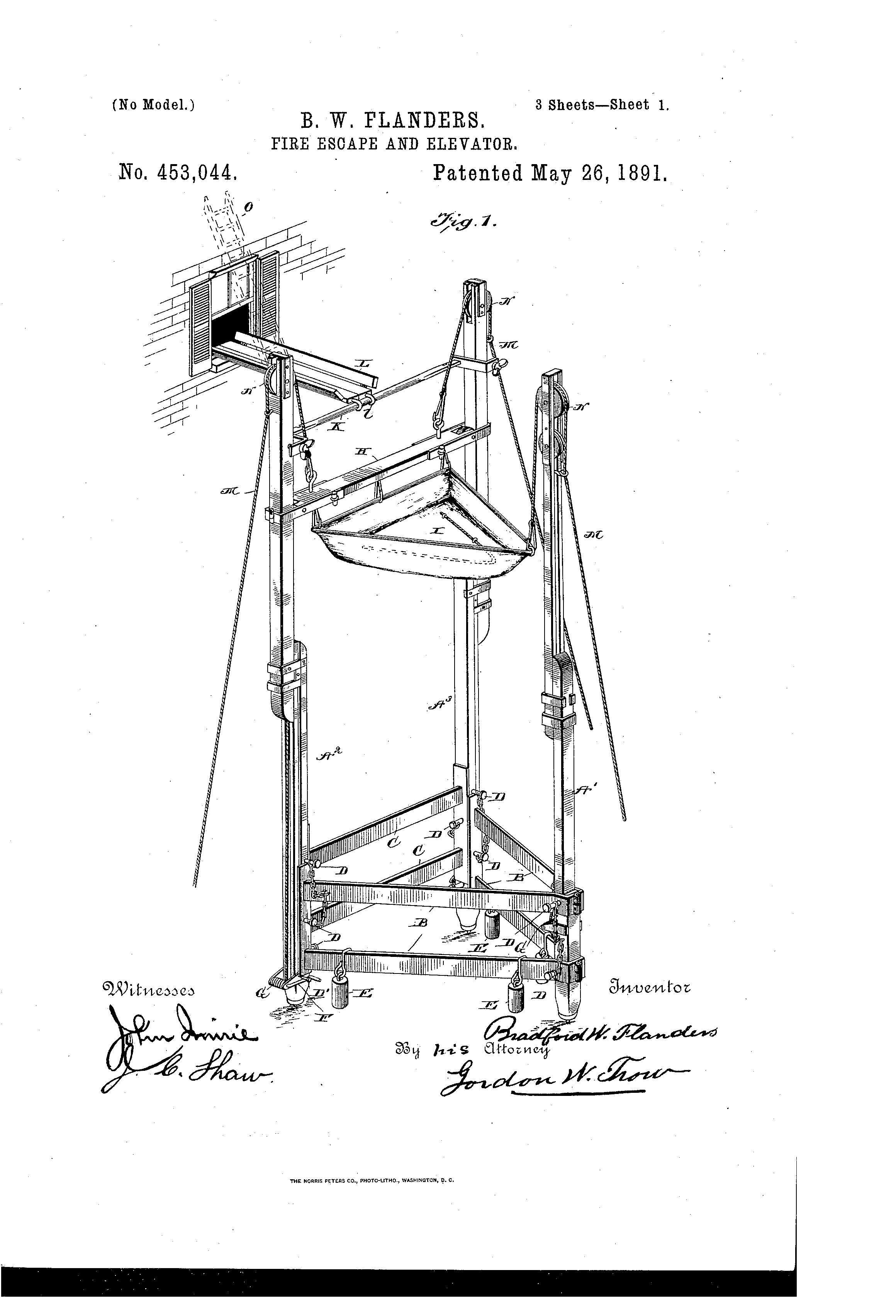

A common design trend seen among patents were ropes, pulleys, slings, and baskets, says Halls. “They often look quite complicated to use and set up, and would require a lot of quick thinking and dexterity under pressure,” she says.

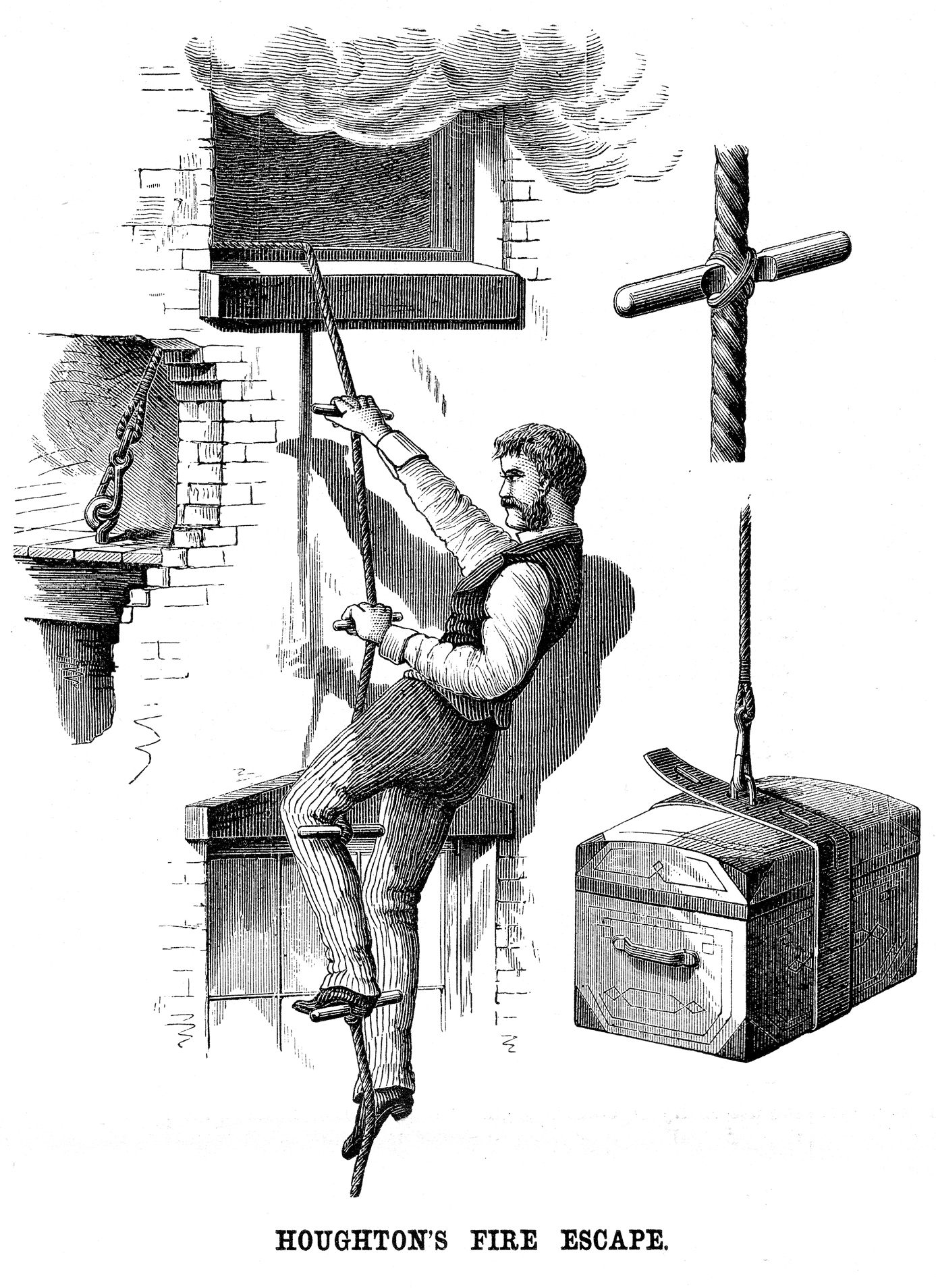

For example, R.H. Houghton’s 1877 fire escape proposal featured pegs tied along a rope to create a flimsy mock ladder that may have been difficult to keep steady if an escapee was trying to quickly descend from a burning building. A few systems operated like an elevator that would be propped and fastened to a window.

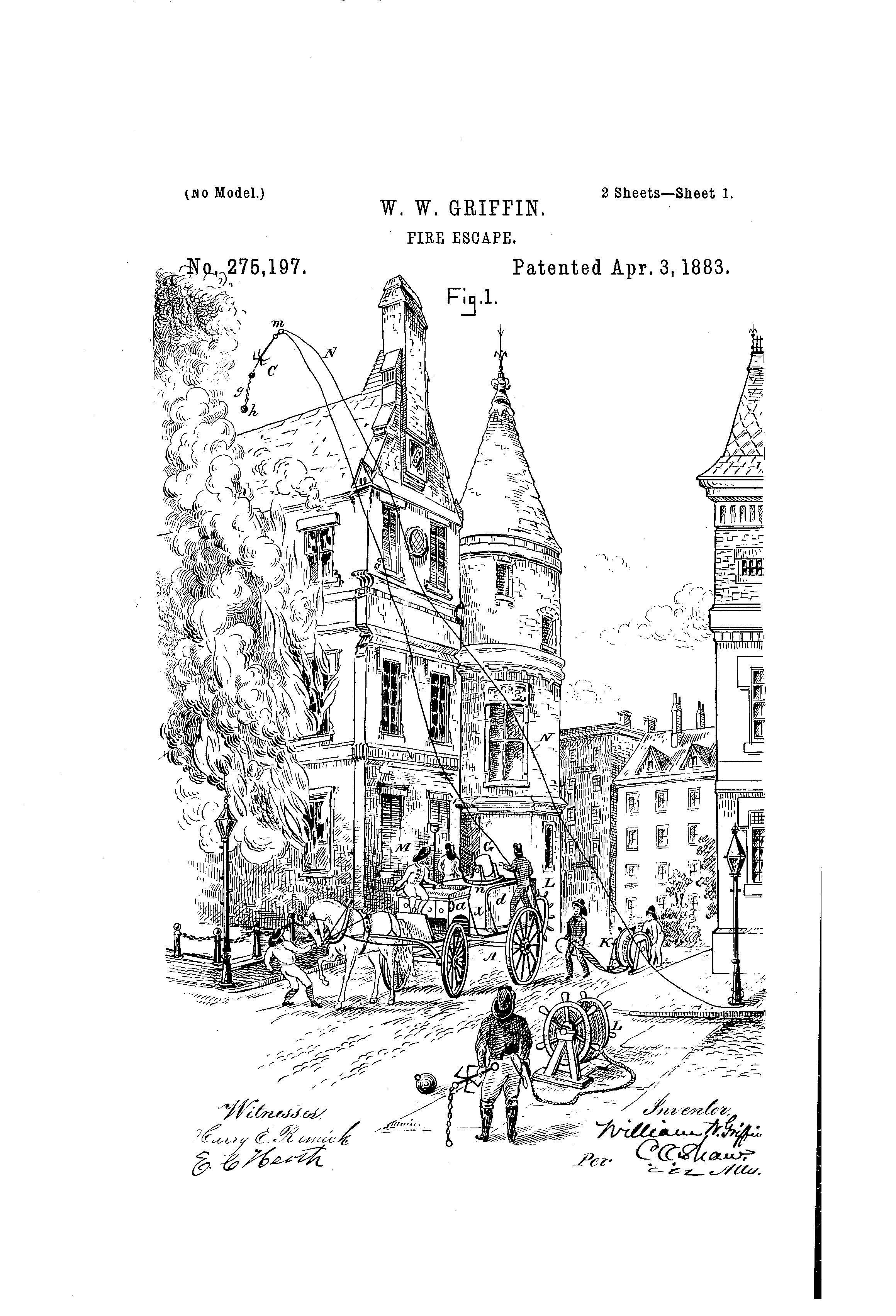

Some officials tried mandating different tactics with ropes, but were met with skepticism. In 1882, retired quartermaster general of the United States Army, Montgomery Meigs, proposed that long bows with heavy metal arrows or hooks and balls of twine be hung inside doors of the government printing office building in Washington.

In Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and other states in the United States, local authorities adopted a rope fire-escape law for hotels, which had the second highest fatality rate after theater fires. The law required hotel owners to place ropes in guestrooms, explains Wermiel. “Such laws, which assumed that frightened hotel guests could climb down ropes from windows high above the street, struck contemporaries as silly,” she wrote.

Tall slides and cloth tubes that gave escapees a direct line of descent to the ground was a popular, and more logical solution. There were a variety of chute designs, from flame retardant canvas, netting, and metal. In the early 20th century, some schools and hospitals installed metal slide chutes to the sides of buildings. Companies still install and utilize similar kinds of escape chutes today.

Over time, the success and failure of different fire escape designs brought forth improved rules and regulations. In 1861, the massive London Tooley Street fire that caused the demise of many warehouses led to new legislation for governing fire services, the adoption of stricter commercial building regulations, and increased fire brigade services in the United Kingdom, Halls wrote.

In the United States, the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist fire at the Asch Building in Greenwich Village in New York City that left 145 workers dead and dozens injured caused a shift towards stricter requirements for exits and fire escapes, Wermiel explains. Because of the horrible incident, architects incorporated fire towers, exterior stairs built with the similar strength of interior stairs, and other alternative exit routes.

The Victorians’ fascination with fires and the fertile ground for enterprise bolstered the number of fire escape designs. The only problem: each of them, says Halls, “seem to carry as many risks as the fire the person was trying to escape from.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook